|

CARDIS '02 Paper

[CARDIS '02 Tech Program Index]

| Pp. 125-134 of the Proceedings |  |

MICROCAST: Smart Card Based (Micro)pay-per-view for

Multicast Services

Josep Domingo-Ferrer, Antoni Martınez-Ballesté and Francesc Sebé

Universitat Rovira i Virgili

Dept. of Computer Engineering and Maths

Av. Paısos Catalans 26,

E-43007 Tarragona, Catalonia

e-mail {jdomingo,anmartin,fsebe}@etse.urv.es

With the increased availability of broadband fixed and mobile

communications, multicast content delivery can be expected

to become a very important market. Especially for wireless

multicast delivery, it is important that payment collection

be fine-grain: the customer should pay only for the content

that she actually consumes. This can be achieved by using

pay-per-view based on micropayments.

This paper proposes the first method for enabling pay-as-you-watch

services in a multicast content delivery

environment. On the customer's side,

micropayment generation is implemented in a smart card which can

be plugged into the customer's receiving device

(computer, digital video receiver, PDA, mobile phone, etc.).

Micropayment collection and verification are distributed among

multicast routers, which avoids bottlenecks inherent to

many-to-one payment transmission.

Keywords: Multicast delivery, Pay-per-view, Pay-as-you-watch,

Micropayments, Smart cards in the Internet.

Introduction

Communication technologies have been evolving in

many important aspects over the last few years.

On one hand, broadband communications such as city-wide WLANs,

ADSL, cable networks and UMTS

are becoming widespread. On the other hand, audio and

video compression codecs such

as DivX, Realmedia, etc. improve the use of the

available bandwidth. Finally, the appearance

of mobile phones with high-resolution color display and

Internet-enabled PDA's will bring

brand new multimedia services to everybody, everywhere.

There are great opportunities to create a huge

market for multimedia content delivery, featuring news broadcasting,

videoconferencing, movie channels, on-line gambling, etc.

Consequently, it seems natural

to use mobile communications and portable devices,

along with traditional desktop PC's, as new privileged outlets

for digital content delivery in pay-per-view mode.

Smart card based micropayments stand out as one of the

most promising solutions

to obtain a fine-grain fee collection service:

the customer uses her smart card to perform micropayments as content

is being received.

Most multimedia delivery services operate

in multicast mode to send content over the Internet.

By using multicast, one single data stream can reach hundreds, thousands and

even millions of target media players.

This paper describes a method for enabling pay-per-view

services in a multicast content delivery

environment. On the customer's side,

micropayment generation is implemented in a smartcard which can

be plugged into the customer's receiving device

(computer, digital video receiver, PDA, mobile phone, etc.).

Micropayment collection and verification are distributed among

multicast routers, which avoids bottlenecks inherent to

many-to-one payment transmission.

Section 2 gives some background on multicast communication;

the use of pay-per-view and micropayments in multicast is also

approached.

Section 3 describes the architecture

of MICROCAST, a system for

pay-per-view multicast content delivery.

The MICROCAST micropayment protocol suite is fully described in

Section 4.

Finally, Section 5 contains some

conclusions and suggestions for future work.

Multicast communication

Depending on the number of receivers, three types of communication

can be distinguished:

- Unicast communication: one source and one receiver.

- Broadcast communication: one source node and all remaining

nodes acting as receivers. As an example, consider

video broadcast in a LAN: the same data are streamed from the

source to the entire network by using the broadcast IP address.

- Multicast communication: one source and a group of receivers.

As an example, consider a local digital cable TV network, where a particular

piece of video content is to be distributed only to subscribers

who are paying for it (rather than to the entire neighborhood).

If a source is to communicate with  receivers, one could

naively think of

using receivers, one could

naively think of

using  unicast communications

(which results in the

source being an output bottleneck) or one broadcast channel

(which results in the entire network being flooded). Both

solutions are wasteful in terms of bandwidth.

It should be noted that the Internet is nowadays already

full of millions of IP packets only controlled by their

time-to-live or by the TCP protocol. unicast communications

(which results in the

source being an output bottleneck) or one broadcast channel

(which results in the entire network being flooded). Both

solutions are wasteful in terms of bandwidth.

It should be noted that the Internet is nowadays already

full of millions of IP packets only controlled by their

time-to-live or by the TCP protocol.

A better option to avoid increasing

network congestion

is for receivers to join a multicast group

and have the content sent to them by using their

multicast group IP address [5,14].

A multicast group  is a set of receivers that are interested

in receiving a particular kind of information. is a set of receivers that are interested

in receiving a particular kind of information.

Efficient multicast design and implementation is currently an open issue.

The multicast task is carried out by multicast routers, which

join previously established multicast groups identified

by a multicast IP address1.

These routers are capable of sending the data flow to multicast group  . .

The basic tasks to be performed in multicast communication are:

advertise the multicast session, manage group enrollment

by the customers who want to receive the stream and, concurrently to

group enrollment, build

the multicast routing tree. Several multicast protocols have

been proposed in the literature, such as

MOSPF[6], PIM-DM[3], PIM-SM[2].

The name ``pay-per-view'' is certainly misleading.

In current digital TV platforms,

a fixed monthly fee is paid to subscribe

to a basic package of channels and services. It is also

possible

to view some special ``pay-per-view events''

(e.g. movies, football matches) by paying in advance

the price corresponding to the event. This form of pay-per-view

means that the content is viewed after the customer

has paid. There are at least two problems with the fee collection

scheme just described. One problem

is that the customer pays for a basic offer that is usually expensive

for her. The other problem is that, in pay-per-view events, the customer

pays for the whole piece of content: if she wants to stop watching

anytime, she is losing a part of her money.

Pay-per-view as contents are being streamed from the server to

the customer (pay-as-you-watch)

seems an option that fits better the customer needs.

Successive payments can be performed every minute, for example.

If a customer switches her player off, she only has

paid for the minutes viewed so far. Of course,

these frequent payment will be small ones, so

credit card transactions or electronic payment systems like SET are

too expensive, too complicated or both [7].

The operating costs of standard electronic payment systems

are unaffordable for small amounts and can be split into communication

and computation costs, the latter being

caused by the use of complex cryptographic techniques such as digital

signatures. Micropayments are electronic payment

methods specifically designed to keep operating costs very low.

In most micropayment systems in the literature,

computational costs are dramatically reduced by replacing digital

signatures with hash functions[11].

For example, this is the case

of PayWord and Micromint[9], where

the security of coin minting rests on one-way hash functions.

The main barrier to using traditional micropayment

schemes for fee collection in multicast environments is their

lack of scalability: a large number of receiving subscribers

eventually overload the source with payment implosion.

The MICROCAST protocol achieves scalability

by distributing

the effort of micropayment collection and verification among

multicast routers. Unlike traditional micropayment schemes,

MICROCAST does not concentrate on minimizing computation for

micropayment generation and verification. By requiring micropayments

to be less frequent (say every few minutes) and

verification to be distributed, MICROCAST can still

use short-exponent discrete exponentiations and provide

the content source with a proof that every customer has paid.

More specifically, the scalability of

our system is based on the following properties not fulfilled

by conventional micropayment schemes (which are inherently unicast):

- Aggregation

- Payments collected by routers at one

level of the multicast tree can be aggregated and

forwarded to the next upper level towards the source.

Each aggregation only requires one product and one addition.

- Single-step verification

- Verifying an aggregated

payment can be done in a single step. There is no

need to verify each individual payment included in

the aggregation, which would imply non-scalability.

Payment verification requires

one short-exponent exponentiation, but this is no problem, since

verification is performed only once per micropayment period

by each tree node (regardless of the number of its child nodes).

Note 1

As it can be seen in

Section 4.4 below,

using the discrete exponentiation as a one-way function

is justified by its homomorphic properties,

which allow

payment aggregation and single-step verification and

are not shared by the (faster) one-way hash functions.

Multicast routers form a group that receives a multicast data stream.

The router will possibly send the info to a hub

that floods all its output connections, thus making the information

reach every node in the subLAN, including

nodes whose customers have not paid for the content.

Cryptography should be used to prevent cheaters from

being able to view the content by using packet sniffers.

Customers in the multicast group have

a decoding key to be able to decode the content

they receive.

Hence, legitimate customers are those who pay every multicast period  (a multicast period typically lasts a few minutes).

When a customer does not pay, she will be considered non-legitimate;

in this case,

a rekeying procedure will start which consists of

distributing a new decoding key to every remaining legitimate customer.

As a result, the removal of a group member will involve

as many unicast transmissions

as legitimate customers remain in the group.

Fortunately, rekeying reaches a maximum cost of

(a multicast period typically lasts a few minutes).

When a customer does not pay, she will be considered non-legitimate;

in this case,

a rekeying procedure will start which consists of

distributing a new decoding key to every remaining legitimate customer.

As a result, the removal of a group member will involve

as many unicast transmissions

as legitimate customers remain in the group.

Fortunately, rekeying reaches a maximum cost of  when using

tree structure controls[12,1].

Even if rekeying is an important multicast issue, the reader of

this paper only needs

to keep in mind that it is the procedure started when a customer

in a multicast group is removed due to lack of valid payment or when a new

customer joins the group. when using

tree structure controls[12,1].

Even if rekeying is an important multicast issue, the reader of

this paper only needs

to keep in mind that it is the procedure started when a customer

in a multicast group is removed due to lack of valid payment or when a new

customer joins the group.

MICROCAST architecture

As it was pointed out in Section 1, MICROCAST is a

pay-as-you-watch system for multicast content delivery.

A typical application for MICROCAST could the pay-as-you-watch video

distribution to thousands of customers. By using

her smart card plugged into her video receiver, a customer

can join a multicast group

when she is interested in watching an event. After joining

a group, the customer makes a micropayment every period  to keep watching the event.

to keep watching the event.

In a conventional micropayment system,

a bottleneck would arise at the video source

as a result of micropayment collection,

because thousands of coins arrive every

period2.

RFC 3170[8] on multicast applications

recommends that multicast protocols

should be able to use the

multicast router link to provide

bidirectional communications instead of using unicast channels

to communicate receivers with the source.

The MICROCAST architecture follows that design principle: multicast

routers handle customers and coins, which results in a dramatical

reduction of the amount of payment data sent to the content source.

The MICROCAST system

consists of a source, a set of multicast routers, the customer smart cards

and receivers, a rekeying

system and a bank (see Figure 1). Each component

is described next:

- Source. The source is the provider of the multicast content.

Typical sources can be a movie channel,

a news service, a music station, a sports service, etc.

The source sells the content to thousands, even millions, of potential

customers. As content is being delivered,

the source expects some kind of payment from customers or at least

something that certifies whether each particular customer

is currently paying.

- Multicast router. The router in the multicast tree

also acts as a micropayment subcollector. It requests micropayment

from its customers and, after a timeout, it collects and

verifies customer micropayments.

Then, the router forwards

valid payments to his parent router in the multicast tree,

in order for payment information to reach the source (or

the main micropayment collector, depending on the business model).

Figure 1:

System architecture for MICROCAST

|

- Customer device. The customer receiving device

(say a digital video receiver) is smart card enabled.

Firstly, the smart card certifies through

some easy calculations (see Section 4)

that a payment is done by

the customer. Thus, the role of the

smart card is twofold: 1) authenticate payment

origin; 2) help enforcing subscription certificate revocation

when the customer is not backed

by enough money in her bank account.

- Rekeying system. The rekeying system maintains a

structure of legitimate customers (those who pay) and

generates and distributes a new decoding key whenever

any router of the system informs that some customer has failed

to pay.

- Bank. The bank's role is to act as certification authority

for customers.

If a customer has enough funds in her account, the bank gives her

a kind of public key (see Section 4).

The MICROCAST protocol suite

The MICROCAST protocol suite consists of protocols

for bank setup, customer subscription, multicast session join,

micropayment, customer removal,

coin redemption and subscriber certificate revocation.

As can be inferred from the previous section,

the bank is a trusted party. It

has a public/private key pair which is used to

issue customer subscription certificates.

The bank setup protocol works as follows:

We next show that publication of  does not turn factoring does not turn factoring

into an easy problem. After Protocol 1,

an intruder knows into an easy problem. After Protocol 1,

an intruder knows  , which is a divisor of , which is a divisor of  .

Equivalently, .

Equivalently,  exists such that exists such that  .

Note that the intruder does not know .

Note that the intruder does not know  . Therefore,

the only strategy to find . Therefore,

the only strategy to find  is by brute search until

an is by brute search until

an  is found such that is found such that  is a divisor of is a divisor of  .

Now, according to Protocol 1, .

Now, according to Protocol 1,

and

and

;

therefore, the intruder only knows

that ;

therefore, the intruder only knows

that

, so brute search of , so brute search of  is computationally infeasible.

is computationally infeasible.

In order to be able to use the system, a customer

needs a subscription certificate. Through this certificate,

the bank certifies that the customer has a bank account

which backs the customer's payments.

Subscription certificates are only valid for a

period  (e.g. one day) and are

generated using the protocol below. Short certificate

validity periods allow implicit revocation to be used in the way

explained in [4]. The duration of

period (e.g. one day) and are

generated using the protocol below. Short certificate

validity periods allow implicit revocation to be used in the way

explained in [4]. The duration of

period  is a trade-off between the cost of

key generation and the risk of revoked keys being re-used

as described in [4]. is a trade-off between the cost of

key generation and the risk of revoked keys being re-used

as described in [4].

The security of the private keys  generated in Protocol 2

is based on the difficulty of computing discrete logarithms

in the subgroup of size

generated in Protocol 2

is based on the difficulty of computing discrete logarithms

in the subgroup of size  generated by generated by  . This problem

is similar to the modulo . This problem

is similar to the modulo  discrete logarithm problem

used in [15]. discrete logarithm problem

used in [15].

Let us assume that, at micropayment period  and at public key validity period

and at public key validity period  ,

a set of customers wish to join

a multicast session ,

a set of customers wish to join

a multicast session  (see Section 3 for an explanation

of what a micropayment period is). To keep the discussion simple and

without loss of generality, we assume

that a session starts and ends within the same public key validity

period (see Section 3 for an explanation

of what a micropayment period is). To keep the discussion simple and

without loss of generality, we assume

that a session starts and ends within the same public key validity

period  . The following joining

protocol is used: . The following joining

protocol is used:

Micropayment protocols

Every time a period  finishes, a customer must perform a

micropayment to keep receiving the content during the next period.

The micropayment collector

(i.e. the router in charge of a group

of customers) asks all customers in his

group to perform the next payment as follows: finishes, a customer must perform a

micropayment to keep receiving the content during the next period.

The micropayment collector

(i.e. the router in charge of a group

of customers) asks all customers in his

group to perform the next payment as follows:

Customers in a group react to micropayment request by generating

a coin using the protocol below:

Coins are generated by customers that correspond to the

multicast tree leaves.

In the last

step of Protocol 5, coins are sent by customers

to parent routers.

Such routers

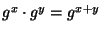

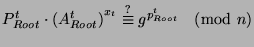

check the validity of the received coins and aggregate

valid coins. Aggregation uses the homomorphic property of

the discrete exponentiation (namely that

),

which is one strong argument in favor of using the discrete

exponentiation as one-way function

(see Note 1).

The aggregated coin is then forwarded by the verifying router

to his parent router and so on

up to the tree root (micropayment collector).

Thus, depending on its level, a router can receive two kinds of coin: ),

which is one strong argument in favor of using the discrete

exponentiation as one-way function

(see Note 1).

The aggregated coin is then forwarded by the verifying router

to his parent router and so on

up to the tree root (micropayment collector).

Thus, depending on its level, a router can receive two kinds of coin:

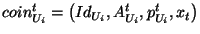

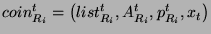

- A single coin from a customer leaf node directly connected

to the router.

- An aggregated coin from a direct child router

(see Protocol 6 below for a description of how coins

are aggregated).

The protocol to aggregate coins by an intermediate router

is as follows:

Protocol 6 (Coin aggregation)

- Initialize the new aggregated coin as

- For each single coin received from customer

, that is, , that is,

, do , do

- For each aggregated coin received from router

, that is, , that is,

, do , do

- Send the aggregated coin

up to the parent router. up to the parent router.

The protocol to check coin validity is:

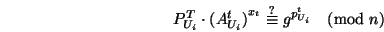

Protocol 7 (Coin validity check)

- If a single coin is received from customer

,

the following check is performed: ,

the following check is performed:

|

(1) |

Note that Check (1) is consistent with the structure

of coins constructed by Protocol 5.

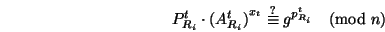

- If an aggregated coin is received from a child router

,

the following check is performed: ,

the following check is performed:

|

(2) |

Lemma 1

Assuming that the discrete logarithm problem as

sketched in Protocol 1 and the RSA

problem are difficult, coin forgery by an intruder is infeasible.

Proof:

To impersonate customer  and

mint a single coin belonging to and

mint a single coin belonging to  at public key validity period

at public key validity period  ,

an intruder knows ,

an intruder knows  and and  and must find and must find

and and  such that Equation (1)

is satisfied. There are two ways to proceed: such that Equation (1)

is satisfied. There are two ways to proceed:

- Follow Protocol 5. In that case, the intruder

must know the legitimate customer's private key

(which is protected by the difficulty of the

discrete logarithm problem over the subgroup generated by

(which is protected by the difficulty of the

discrete logarithm problem over the subgroup generated by  ). ).

- Generate a random

and compute and compute  as as

Now, given  , computing , computing

without

knowing the factorization of without

knowing the factorization of  is the RSA problem. is the RSA problem.

Forging an aggregate coin that satisfies Equation 2

is analogous.

Lemma 2

The security of a customer's private key does not decrease

as the number of coins she mints increases.

Proof:

Without loss of generality, compare the situation where one

coin has been minted with the situation where two coins have

been minted. Assume one coin has been generated during

micropayment period  and public key validity period

and public key validity period  . Then the following

equation holds: . Then the following

equation holds:

where, only  and and  are known to possible

intruders (such quantities are part of the coin). Thus,

there is one equation and two unknowns are known to possible

intruders (such quantities are part of the coin). Thus,

there is one equation and two unknowns  and and

, so , so  cannot be determined.

If a second coin is generated during micropayment period cannot be determined.

If a second coin is generated during micropayment period

the number of equations increases to two, but there are

now three unknowns  , ,  and and  .

In general, it can be seen that generation of .

In general, it can be seen that generation of  coins

results in coins

results in  equations with equations with  unknowns, one of which

is the customer's private key unknowns, one of which

is the customer's private key  . .  . .

Customer removal from a group is caused by lack of valid payment.

There may be two situations behind the lack of valid payment:

1) a customer does not send any coin to her parent router;

2) a customer sends an invalid coin to her parent router.

Both situations are handled by the following protocol:

During a multicast session, the micropayment collector

stores the final aggregated coin for each performed

micropayment. This coin contains a list including

the identifiers of all customers that performed a payment.

When the number of collected coins is large enough,

the micropayment collector contacts the bank

in order to redeem them.

Protocol 9 (Coin redemption)

- When the aggregated coin corresponding to period

has to be redeemed, the micropayment collector

sends to the bank the session identifier has to be redeemed, the micropayment collector

sends to the bank the session identifier

, the session start date and time , the session start date and time

, the value , the value  of individual coins

in that session, the micropayment period of individual coins

in that session, the micropayment period  , and

the final aggregated coin , and

the final aggregated coin

- The bank does:

- If this is the first coin redemption of the current

multicast session then

check that the public key of all customers in the list

field is correctly certified and compute

. .

- If this is not the first coin redemption of the session,

then

- If

in in  is the

same as is the

same as

in in

, then , then

. .

- If

, then obtain , then obtain

as the modulo as the modulo  product of

product of

times the public keys of the new

customers times the multiplicative inverses of the

public keys of the removed customers. times the public keys of the new

customers times the multiplicative inverses of the

public keys of the removed customers.

- Compute

- Check

- If all checks are correct, transfer the appropriate

amounts from each customer account to the account of the

micropayment collector

(or directly to the account of the multicast content source,

depending on the business model). In order to avoid

performing microtransfers from each customer, a better strategy

is to cluster several successive micropayments

and perform a larger transfer from each customer.

It is possible for a customer to run out of funds before all

of her certificates expire. In this situation, it would be possible

for her to perform micropayments not backed by enough funds

in her bank account.

This situation is detected by the bank during coin

redemption. In this case, the bank would revoke all

her subscription certificates for future time intervals.

The implicit revocation mechanism described in [4]

is used: the bank does not supply any more encrypted private

keys to the customer's smart card for joining the session

in subsequent periods (Protocol 3).

Conclusions and future work

A micropayment protocol suite for multicast pay-per-view

content delivery has been presented. The customer is represented

by her smart card in all protocols in the suite. The proposed

scheme has been simulated and works well as long as synchronization

between customers is maintained.

The main goal of the protocol is to

to distribute micropayment collection so as eliminate the

bottleneck associated to Mto1 applications.

Future work will be directed

to scenarios where synchronization within a multicast group has

been lost. A second line of work is to speed up coin

generation by the customer smart card and coin validity check

by routers: this would require replacing the discrete exponentiation

with a faster homomorphic one-way function.

This work has been partly supported by the European

Commission under project IST-2001-32012

``Co-Orthogonal Codes'' and by the Spanish

Ministry of Science and Technology and the European FEDER

Fund under project TIC2001-0633-C03-01 ``STREAMOBILE''.

-

- 1

- G. Caronni, K. Waldvogel, D. Sun and B. Plattner,

``Efficient security for large and dynamic multicast

groups'', in IEEE 7th Workshop on Enabling Technologies: Infrastructure

for Collaborative Enterprises (WET ICE '98). Los Alamitos CA:

IEEE Computer Society, pp. 376-383, 1998.

- 2

- S. Deering, D. Estrin, D. Farinacci, V. Jacobson, C. Liu

and L. Wei,

``The PIM architecture for wide-area multicast routing'',

IEEE/ACM Transactions on Networking, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 153-162,

Apr. 1996.

- 3

- S. Deering, D. Estrin, D. Farinacci, V. Jacobson,

A. Helmy, D. Meyer and L. Wei, ``Protocol independent multicast

version 2 dense mode specification'', IETF Internet Draft, Nov. 1998.

http://www.ietf.org

- 4

- J. Domingo-Ferrer, M. Alba and F. Sebé,

``Asynchronous large-scale certification based on

certificate verification trees'', in

Communications and Multimedia Security'2001. Norwell MA:

Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 185-196, 2001.

- 5

- C. K. Miller, Multicast Newtorking and Applications.

Reading MA: Addison Wesley, 1999.

- 6

- J. Moy, ``Multicast extensions to OSPF'', Internet

RFC 1584, March 1994. http://www.ietf.org

- 7

- R. Oppliger, Security Technologies for the World Wide Web.

Norwood MA: Artech House, 2000.

- 8

- B. Quinn and K. Almeroth,

``IP multicast applications: challenges and solutions'',

Internet RFC 3170, Sept. 2001. http://www.ietf.org.

- 9

- R. Rivest and A. Shamir, ``PayWord and Micromint: Two simple

micropayment schemes'', Technical Report, MIT LCS, Nov. 1995.

- 10

- R. L. Rivest, A. Shamir and L. Adleman,

``A method for obtaining digital signatures and public-key cryptosystems'',

Communications of the ACM, vol. 21, pp. 120-126, Feb. 1978.

- 11

- B. Schneier, Applied Cryptography. New York: Wiley, 1996.

- 12

- J. Snoeyink, S. Suri and G. Varghese,

``A lower bound for multicast key

distribution'', in Proceedings of IEEE INFOCOM 2001. Piscataway NJ:

IEEE Computer and Communications Society, pp. 422-431, 2001.

- 13

- D. R. Stinson, Cryptography. Theory and Practice,

Boca Raton FL: CRC Press, 1995.

- 14

- R. Wittmann and M. Zitterbart,

Multicast Communication, Protocols and Applications.

San Mateo CA: Morgan Kaufmann, 2001.

- 15

- Digital Signature Standard, FIPS PUB 186,

National Institute of Standards, Washington D. C., May 1994.

MICROCAST: Smart Card Based (Micro)pay-per-view for

Multicast Services

This document was generated using the

LaTeX2HTML translator Version 2K.1beta (1.50)

Copyright © 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996,

Nikos Drakos,

Computer Based Learning Unit, University of Leeds.

Copyright © 1997, 1998, 1999,

Ross Moore,

Mathematics Department, Macquarie University, Sydney.

The command line arguments were:

latex2html -html_version 3.2,unicode -t MICROCAST -split 0 -no_navigation index.tex

Footnotes

- ... address1

- Multicast addresses are IP numbers

in the range between 224.0.0.0 and 239.255.255.255

- ...

period2

- A coin can be a 200-bit vector, and

period

is short enough

to keep payment fine grain, i.e.

for content reception and payment to progress nearly concurrently. is short enough

to keep payment fine grain, i.e.

for content reception and payment to progress nearly concurrently.

Antoni Martinez

2002-09-19

|