Thresher: An Efficient Storage Manager for Copy-on-write Snapshots

Liuba Shrira1

Department of Computer Science

Brandeis University

Waltham, MA 02454

-

Hao Xu

Department of Computer Science

Brandeis University

Waltham, MA 02454

Abstract:

A new generation of storage systems exploit decreasing storage costs

to allow applications to take

snapshots of past states and retain them for long durations.

Over time, current snapshot techniques can produce large volumes of snapshots.

Indiscriminately keeping all snapshots accessible is impractical,

even if raw disk storage is cheap,

because administering such large-volume storage is expensive over a long duration.

Moreover, not all snapshots are equally valuable.

Thresher is a new snapshot storage management system,

based on novel copy-on-write snapshot techniques,

that is the first to provide applications the ability to discriminate

among snapshots efficiently.

Valuable snapshots can remain

accessible or stored with faster access

while less valuable snapshots are

discarded or moved off-line.

Measurements of the Thresher prototype indicate that the new techniques are efficient and

scalable,

imposing minimal ( )

performance penalty on expected common workloads.

)

performance penalty on expected common workloads.

1 Introduction

A new generation of storage systems exploit decreasing storage costs and

efficient versioning techniques to allow applications to take

snapshots of past states and retain them for long durations.

Snapshot analysis is becoming increasingly important.

For example,

an ICU monitoring system may analyze the information on patients' past response

to treatment.

Over time, current snapshot techniques can produce large volumes of snapshots.

Indiscriminately keeping all snapshots accessible is impractical,

even if raw disk storage is cheap,

because administering such large-volume storage is expensive over a long

duration.

Moreover, not all snapshots are equally valuable.

Some are of value for a long time, some for a short time.

Some may require faster access.

For example,

a patient monitoring system might retain readings showing an abnormal behavior.

Recent snapshots may require faster access than older snapshots.

Current snapshot systems do not provide applications with the ability to

discriminate efficiently among snapshots,

so that valuable snapshots remain

accessible while less valuable snapshots are discarded or moved off-line.

The problem is that incremental copy-on-write,

the basic technique that makes snapshot creation efficient,

entangles on the disk successive snapshots.

Separating entangled snapshots creates disk fragmentation

that reduces snapshot system performance over time.

This paper describes Thresher, a new snapshot storage management system,

based on a novel snapshot technique,

that is the first to provide applications the ability to discriminate

among snapshots efficiently.

An application provides a discrimination policy that

ranks snapshots. The policy can be specified

when snapshots are taken, or

later, after snapshots have been created.

Thresher efficiently disentangles differently ranked snapshots,

allowing valuable snapshots to be stored with faster access or to

remain accessible for longer,

and allowing less-valuable snapshots to be discarded,

all without creating disk fragmentation.

Thresher is based on two key innovations.

First, a novel technique called ranked segregation

efficiently separates on disk the states of differently-ranked copy-on-write

snapshots, enabling no-copy reclamation without fragmentation.

Second, while most snapshot systems rely on a no-overwrite update approach,

Thresher relies on a novel update-in-place technique that provides an

efficient way to transform snapshot representation as snapshots are created.

The ranked segregation technique can be efficiently composed

with different snapshot representations

to lower the storage management costs for several useful

discrimination policies.

When applications need to defer snapshot discrimination,

for example until after examining one or more subsequent snapshots to identify abnormalities,

Thresher segregates the normal and abnormal snapshots efficiently by composing

ranked segregation with a compact diff-based representation to reduce the cost of copying.

For applications that need faster access to recent snapshots,

Thresher composes ranked segregation with a dual snapshot

representation that

is less compact but provides faster access.

A snapshot storage manager, like a garbage collector,

must be designed with a concrete system in mind,

and must perform well for different application workloads.

To explore how the performance of our new techniques depends on the

storage system workload,

we prototyped Thresher in an experimental snapshot system [12]

that allows

flexible control of workload parameters.

We identified two such parameters, update density and overwriting,

as the key parameters that determine the

performance of a snapshot storage manager.

Measurements of the Thresher prototype indicate that our new techniques are efficient and scalable,

imposing minimal ( )

performance penalty on common expected workloads.

)

performance penalty on common expected workloads.

2 Specification and context

In this section we specify Thresher, the snapshot storage

management system that allows applications to discriminate among snapshots.

We describe Thresher in the context of a concrete system

but we believe our techniques are more general. Section 3

points out the snapshot system dependent features of Thresher.

Thresher has been designed for a snapshot system called SNAP [12].

SNAP assumes that applications are structured as

sequences of transactions accessing a storage system.

It supports

Back-in-time execution (or, BITE), a capability of a storage system

where applications running general code can run

against read-only snapshots in addition to the current state.

The snapshots reflect transactionally consistent historical states.

An application can choose which snapshots it wants to access

so that snapshots can reflect states meaningful to the application.

Applications can take snapshots at unlimited

"resolution" e.g. after each transaction, without

disrupting access to the current state.

Thresher allows applications to discriminate among snapshots

by incorporating a snapshot discrimination policy into the following three snapshot

operations:

a request to take a snapshot (snapshot request, or declaration) that

provides a discrimination policy,

or indicates lazy discrimination,

a request to access a snapshot (snapshot access),

and a request to specify a discrimination policy for a snapshot (discrimination request).

The operations have the following semantics.

Informally, an application takes a snapshot by asking for a snapshot ``now''.

This snapshot request is serialized along with other transactions and

other snapshots.

That is, a snapshot reflects all state-modifications by transactions serialized

before this request,

but does not reflect modifications by transactions serialized after.

A snapshot request returns a snapshot name that applications

can use to refer to this snapshot later, e.g. to specify a discrimination policy

for a snapshot.

For simplicity,

we assume snapshots are assigned unique sequence numbers

that correspond to the order in which they occur.

A snapshot access request specifies which snapshot an application

wants to use for back-in-time execution.

The request returns a consistent set of object states,

allowing the read-only transaction to run as if it were running against the

current storage state.

A discrimination policy ranks snapshots. A rank is

simply a numeric score assigned to a snapshot.

Thresher interprets the ranking to determine the relative lifetimes of snapshots

and the relative snapshot access latency.

A snapshot storage management system needs to be efficient

and not unduly slow-down the snapshot system.

3 The snapshot system

Thresher is implemented in SNAP [12], the snapshot system

that provides snapshots for the Thor [7] object storage system.

This section reviews the baseline storage and snapshot systems, using

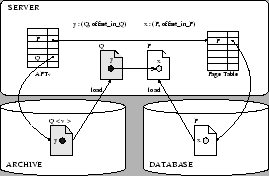

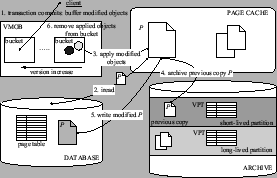

Figure 3 to trace their execution within Thresher.

Our general approach to snapshot discrimination

is applicable to snapshot systems that separate snapshots

from the current storage system state.

Such so-called split snapshot systems [16]

rely on update-in-place storage and create snapshots by copying out the past states,

unlike snapshot systems that rely on no-overwrite storage and

do not separate snapshot and current states [13].

Split snapshots are attractive in long-lived systems because

they allow creation of high-frequency snapshots without disrupting access

to the current state while preserving the on-disk object clustering for the current state [12].

Our approach takes advantage of the separation between snapshot and current states to

provide efficient snapshot discrimination. We create a specialized snapshot representation

tailored to the discrimination policy while copying out the past states.

3.1 The storage system

Thor has a client/server architecture.

Servers provide persistent

storage (called database storage) for objects.

Clients cache copies of the objects and run applications that

interact with the system by making calls to methods of cached objects.

Method calls occur within a the context of transaction.

A transaction commit causes

all modifications to become persistent, while an abort leaves

no transaction changes in the persistent state.

The system uses optimistic concurrency control [1].

A client

sends its read and write object sets with modified object states to the server

when the application asks to commit the transaction.

If no conflicts were detected, the server commits the transaction.

An object belongs to a particular server. The object within

a server is uniquely identified by an object reference (Oref).

Objects are clustered into 8KB pages.

Typically objects are small and

there are many of them in a page. An object Oref is composed of a

PageID and a

oid. The PageID identifies the containing page and allows the lookup

of an object location using a page table.

The oid is an index into an offset table

stored in the page. The offset table contains the object

offsets within the page.

This indirection allows us to move an object within a page

without changing the references to it.

When an object is needed by a transaction, the client fetches

the containing page from the server. Only

modified objects are shipped back to the server when the

transaction commits.

Thor provides transaction durability using the ARIES no-force

no-steal redo log protocol [5].

Since only modified objects are shipped back at commit time,

the server may need to do an

installation read (iread) [8]

to obtain the containing page from disk.

An in-memory, recoverable cache

called the modified object buffer(MOB)

stores the committed modifications allowing to defer ireads

and increase write absorption [4,8]. The modifications

are propagated to the disk by a background cleaner thread that

cleans the MOB.

The cleaner processes the MOB in transaction log order to facilitate

the truncation of the transaction log. For each modified object

encountered, it reads the page containing the object from disk (iread)

if the page is not cached, installs all

modifications in the MOB for objects in that page,

writes the updated page back to disk, and removes the objects from the MOB.

The server also manages an in-memory page cache used to serve

client fetch requests. Before returning a requested page to the client,

the server updates the cache copy, installing all modifications in the MOB

for that page so that the fetched page reflects the up-to-date

committed state.

The page cache uses LRU replacement but discards

old dirty pages (it depends on ireads to read them back

during MOB cleaning)

rather than writing them back to

disk immediately.

Therefore the cleaner thread is the only component of the system

that writes pages to disk.

3.2 Snapshots

SNAP creates snapshots by copying out the past storage system states onto a separate snapshot archive disk.

A snapshot provides

the same abstraction as the storage system, consisting of

snapshot pages and a snapshot page table.

This allows unmodified application code running in the storage system

to run as BITE over a snapshot.

SNAP copies snapshot pages and snapshot page table mappings into the archive during cleaning.

It uses an incremental copy-on-write technique specialized for split snapshots:

a snapshot page is

constructed and copied into the archive when a page on the database disk is about to be overwritten

the first time after a snapshot is declared.

Archiving a page creates a snapshot page table mapping for the archived page.

Consider the pages of snapshot  and page table mappings over the transaction history

starting with the snapshot

and page table mappings over the transaction history

starting with the snapshot  declaration.

At the declaration point, all snapshot

declaration.

At the declaration point, all snapshot  pages are in the database

and all the snapshot

pages are in the database

and all the snapshot  page table mappings point to the database.

Later, after several update transactions have committed modifications,

some of the snapshot

page table mappings point to the database.

Later, after several update transactions have committed modifications,

some of the snapshot  pages may have been copied into the archive,

while the rest are still in the database.

If a page

pages may have been copied into the archive,

while the rest are still in the database.

If a page  has not been modified since

has not been modified since  was declared, snapshot page

was declared, snapshot page  is in the database. If

is in the database. If  has been modified since

has been modified since  was declared, the snapshot

was declared, the snapshot

version of

version of  is in the archive.

The snapshot

is in the archive.

The snapshot  page table mappings track this information, i.e. the archive or database

address of each page in snapshot

page table mappings track this information, i.e. the archive or database

address of each page in snapshot  .

.

3.2.0.1 Snapshot access.

We now describe how

BITE of unmodified application code running on a snapshot

uses a snapshot page table to look up

objects and transparently redirect

object references within a snapshot between database and archive pages.

To request a snapshot  , a client application sends

a snapshot access request to the server.

The server constructs an archive page table (APT) for version

, a client application sends

a snapshot access request to the server.

The server constructs an archive page table (APT) for version  (

( )

and ``mounts'' it for the client.

)

and ``mounts'' it for the client.

maps each page in snapshot

maps each page in snapshot  into its archive address or

indicates the page is in the database.

Once

into its archive address or

indicates the page is in the database.

Once  is mounted, the server receiving a page fetch requests from the client

looks up

pages in

is mounted, the server receiving a page fetch requests from the client

looks up

pages in  and reads them from either archive or database.

Since snapshots are accessed read-only,

and reads them from either archive or database.

Since snapshots are accessed read-only,

can be shared by all clients mounting snapshot

can be shared by all clients mounting snapshot  .

.

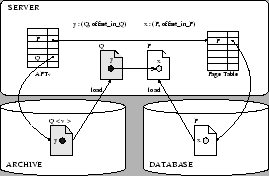

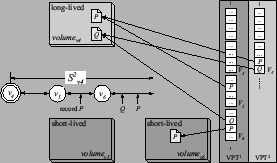

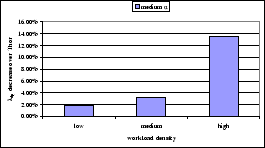

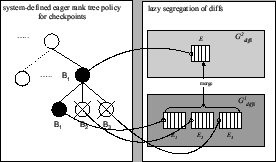

Figure 1:

BITE: page-based representation

|

Figure 1 shows an example of how unmodified

client application code accesses objects in snapshot  that includes

both archived and database pages.

For simplicity, the example assumes a server state where all committed

modifications have been already propagated to the database and the archive disk.

In the example, client code requests object

that includes

both archived and database pages.

For simplicity, the example assumes a server state where all committed

modifications have been already propagated to the database and the archive disk.

In the example, client code requests object  on page

on page  ,

the server looks up

,

the server looks up  in

in  ,

loads page

,

loads page  from the archive and sends it to the client.

Later on client code follows a reference from

from the archive and sends it to the client.

Later on client code follows a reference from  to

to  in the client cache,

requesting object

in the client cache,

requesting object  in page

in page

from the server. The server looks up

from the server. The server looks up  in

in  and finds out that

the page

and finds out that

the page  for snapshot

for snapshot  is still in the database.

The server reads

is still in the database.

The server reads  from the database and sends it to the client.

from the database and sends it to the client.

In SNAP, the archive representation for a snapshot page includes the complete

storage system page. This representation is refered to as page-based.

The following sections describe different snapshot page representations,

specialized to various discrimination policies.

For example, a snapshot page can have

a more compact representation based on modified object diffs, or it can have two different representations.

Such variations in snapshot representation are transparent to the application code running BITE,

since the archive read operation

reconstructs the snapshot page into storage system representation before sending it

to the client.

3.2.0.2 Snapshot creation.

The notions of a snapshot span and pages recorded by a snapshot

capture the incremental copy-on-write manner by which SNAP archives

snapshot pages and snapshot page tables.

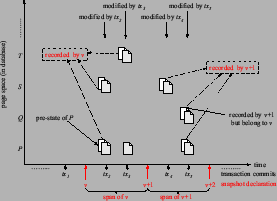

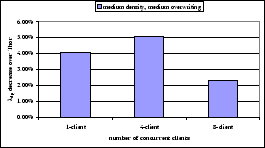

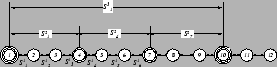

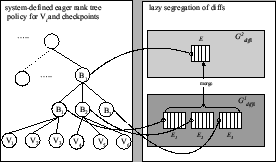

Figure 2:

Split copy-on-write

|

Snapshot declarations partition transaction history into spans. The span of a snapshot  starts with its declaration and ends with the declaration of the next snapshot (

starts with its declaration and ends with the declaration of the next snapshot ( ).

Consider the first modification of a page

).

Consider the first modification of a page  in a span of a snapshot

in a span of a snapshot  .

The pre-state of

.

The pre-state of  belongs to snapshot

belongs to snapshot  and has to be eventually copied into the archive.

We say snapshot

and has to be eventually copied into the archive.

We say snapshot  records its version of

records its version of  .

In Figure 2,

snapshot

.

In Figure 2,

snapshot  records pages

records pages  and

and  (retaining the pre-states modified by transaction

(retaining the pre-states modified by transaction  ) and

the page

) and

the page  (retaining the pre-state modified by transaction

(retaining the pre-state modified by transaction  ). Note that there is no need to retain the pre-state of

page

). Note that there is no need to retain the pre-state of

page  modified by transaction

modified by transaction  since it is not the first modification of

since it is not the first modification of  in the span.

in the span.

If  does not record a version of page

does not record a version of page  , but

, but  is modified after

is modified after  is declared,

in a span of a later snapshot, the later snapshot records

is declared,

in a span of a later snapshot, the later snapshot records  's version of

's version of  .

In above example,

.

In above example,  's version of page

's version of page  is recorded by a later

snapshot

is recorded by a later

snapshot  who also records its own version of

who also records its own version of  .

.

Snapshot pages are constructed and copied into the archive during cleaning when

the pre-states of modified pages about to be overwritten in the database are available in memory.

Since the cleaner runs asynchronously with the snapshot declaration,

the snapshot system needs to prevent snapshot states from being overwritten by the

on-going transactions.

For example, if several snapshots are declared between two successive cleaning rounds,

and a page  gets modified after each snapshot declaration,

the snapshot system has to retain a different version of

gets modified after each snapshot declaration,

the snapshot system has to retain a different version of  for each snapshot.

for each snapshot.

SNAP prevents snapshot state overwriting, without blocking the on-going transactions. It

retains the pre-states needed for snapshot creation in an in-memory data structure

called versioned modified object buffer (VMOB).

VMOB contains a queue of buckets, one for each snapshot. Bucket  holds

modifications committed in

holds

modifications committed in  's span.

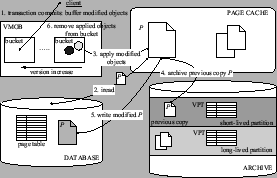

As transactions commit modifications, modified objects are added to the bucket of the latest snapshot (Step 1, Figure 3).

The declaration of a new snapshot creates a new

mutable bucket, and makes the preceding snapshot bucket immutable, preventing

the overwriting of the needed snapshot states.

's span.

As transactions commit modifications, modified objects are added to the bucket of the latest snapshot (Step 1, Figure 3).

The declaration of a new snapshot creates a new

mutable bucket, and makes the preceding snapshot bucket immutable, preventing

the overwriting of the needed snapshot states.

A cleaner updates the database by cleaning the modifications in the VMOB,

and in the process of cleaning, constructs the snapshot pages for archiving.

Steps 2-5 in Figure 3 trace this process.

To clean a page  ,

the cleaner first obtains a database copy of

,

the cleaner first obtains a database copy of  .

The cleaner then uses

.

The cleaner then uses  and the modifications in the buckets to create all

the needed snapshot versions of

and the modifications in the buckets to create all

the needed snapshot versions of  before updating

before updating  in the database.

Let

in the database.

Let  be the first bucket containing modifications to

be the first bucket containing modifications to  , i.e. snapshot

, i.e. snapshot  records its version of

records its version of  .

The cleaner constructs the version of

.

The cleaner constructs the version of  recorded by

recorded by  simply by

using the database copy of

simply by

using the database copy of  .

The cleaner then updates

.

The cleaner then updates  by applying modifications in bucket

by applying modifications in bucket  ,

removes the modifications from the bucket

,

removes the modifications from the bucket  , and proceeds to the following bucket.

The updated

, and proceeds to the following bucket.

The updated  will be the version of

will be the version of  recorded by the snapshot that has the next modification to

recorded by the snapshot that has the next modification to  in its bucket.

This process is repeated for all pages with modifications in VMOB,

constructing the recorded snapshot pages for the snapshots corresponding to

the immutable VMOB buckets.

in its bucket.

This process is repeated for all pages with modifications in VMOB,

constructing the recorded snapshot pages for the snapshots corresponding to

the immutable VMOB buckets.

The cleaner writes the recorded pages into the archive sequentially in snapshot order,

thus creating incremental snapshots.

The mappings for the archived snapshot pages are collected

in versioned incremental snapshot page tables.

VPT (versioned page table for snapshot

(versioned page table for snapshot  )

is a data structure

containing the mappings (from page id to archive address)

for the pages recorded by snapshot

)

is a data structure

containing the mappings (from page id to archive address)

for the pages recorded by snapshot  .

As pages recorded by

.

As pages recorded by  are archived, mappings are inserted into VPT

are archived, mappings are inserted into VPT .

After all pages recorded by

.

After all pages recorded by  have been archived, VPT

have been archived, VPT is archived as well.

is archived as well.

The cleaner writes the VPTs sequentially, in snapshot order, into a separate archive data structure.

This way, a forward sequential scan through the archived incremental page tables

from VPT and onward

finds the mappings for all the archived pages that belong to snapshot

and onward

finds the mappings for all the archived pages that belong to snapshot  .

Namely, the mapping for

.

Namely, the mapping for  version of page

version of page  is found either in VPT

is found either in VPT ,

or, if not there, in the VPT of the first subsequently declared snapshot that records

,

or, if not there, in the VPT of the first subsequently declared snapshot that records  .

SNAP efficiently bounds the length of the scan [12].

For brevity, we do not review the bounded scan protocol here.

.

SNAP efficiently bounds the length of the scan [12].

For brevity, we do not review the bounded scan protocol here.

To construct a snapshot page table for snapshot  for BITE,

SNAP needs to identify the snapshot

for BITE,

SNAP needs to identify the snapshot  pages that are

in the current database.

HAV is an auxiliary data structure that tracks the highest archived

version for each page. If HAV

pages that are

in the current database.

HAV is an auxiliary data structure that tracks the highest archived

version for each page. If HAV , the

snapshot

, the

snapshot  page

page  is in the database.

is in the database.

4 Snapshot discrimination

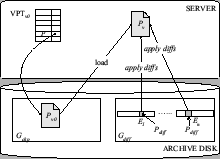

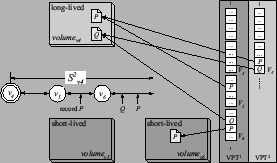

Figure 3:

Archiving split snapshots

|

A snapshot discrimination policy may specify that older snapshots

outlive more recently declared snapshots.

Since snapshots are archived incrementally,

managing storage for snapshots

according to such a discrimination policy can be costly.

Pages that belong to a longer-lived snapshot may be recorded

by a later short-lived snapshot thus entangling short-lived and long-lived pages.

When different lifetime pages are entangled, discarding

shorter-lived pages creates archive storage fragmentation.

For example, consider two consecutive snapshots  and

and  in Figure 2,

with

in Figure 2,

with  recording pages versions

recording pages versions  , and

, and  , and

, and

recording pages P

recording pages P ,

,  and

and  .

The page

.

The page  recorded by

recorded by  belongs to both snapshots

belongs to both snapshots  and

and  .

If the discrimination policy specifies that

.

If the discrimination policy specifies that  is long-lived but

is long-lived but

is transient, reclaiming

is transient, reclaiming

before

before  creates disk fragmentation. This is because

we need to reclaim

creates disk fragmentation. This is because

we need to reclaim  and

and  but

not

but

not  since

since  is needed by the long-lived

is needed by the long-lived  .

.

In a long-lived system, disk fragmentation degrades

archive performance causing non-sequential archive disk writes.

The alternative approach that

copies out the pages of the long-lived snapshots,

incurs the high cost of random disk reads.

But to remain non-disruptive,

the snapshot system needs to keep the archiving costs low,

i.e. limit the amount of archiving I/O

and rely on low-cost sequential archive writes.

The challenge is to support snapshot discrimination efficiently.

Our approach

exploits the copying of past states in a split snapshot system.

When the application provides a snapshot discrimination policy

that determines the lifetimes of snapshots,

we segregate the long-lived and the short-lived

snapshot pages and copy different lifetime pages into different archive areas.

When no long-lived pages are stored in short-lived areas,

reclamation creates no fragmentation.

In the example above, if the archive system knows at snapshot  creation time that it is shorter-lived than

creation time that it is shorter-lived than  ,

it can store the long-lived snapshot pages

,

it can store the long-lived snapshot pages  ,

,  and

and  in a long-lived archive area, and

the transient

in a long-lived archive area, and

the transient  ,

,  pages in a short-lived area, so

that the shorter-lived pages can be reclaimed without fragmentation.

pages in a short-lived area, so

that the shorter-lived pages can be reclaimed without fragmentation.

Our approach therefore, combines a discrimination policy and a discrimination mechanism.

Below we characterize the discrimination policies supported

in Thresher. The subsequent sections describe the discrimination mechanisms for different policies.

4.0.0.1 Discrimination policies.

A snapshot discrimination policy conveys to the snapshot storage management system

the importance of snapshots so that

more important snapshots can have longer lifetimes, or can be stored with faster access.

Thresher supports a class of flexible discrimination policies described below

using an example.

An application specifies a discrimination policy by providing a relative snapshot ranking.

Higher-ranked snapshots are deemed more important.

By default, every snapshot is created with a lowest rank. An application can "bump up" the importance of a snapshot

by assigning it a higher rank.

In a hospital ICU patient database, a policy may assign

the lowest rank to snapshots corresponding to minute by minute

vital signs monitor readings, a higher rank to the monitor readings that

correspond to hourly nurses' checkups,

yet a higher rank to the readings viewed in doctors' rounds.

Within a given rank level, more recent snapshots are considered more important.

The discrimination policy assigns longer lifetimes to more important snapshots,

defining a 3-level sliding window hierarchy of snapshot lifetimes.

The above policy is a representative of a general class of discrimination policies

we call rank-tree.

More precisely, a k-level rank-tree policy has the following properties,

assuming rank levels are given integer values  through

through  :

:

- RT1: A snapshot ranked as level

,

,  , corresponds to a snapshot at each lower rank level from

, corresponds to a snapshot at each lower rank level from  to

to  .

.

- RT2: Ranking a snapshot at a higher rank level increases its lifetime.

- RT2: Within a rank level, more recent snapshots outlive older snapshots.

Figure 4 depicts a 3-level rank-tree policy for the hospital example,

where snapshot number 1, ranked at level 3, corresponds to a monitor reading that was sent for inspection to both

the nurse and the doctor, but snapshot number 4 was only sent to the nurse.

An application can specify a rank-tree policy eagerly by providing

a snapshot rank at snapshot declaration time, or lazily, by providing

the rank after declaring a snapshot.

An application can also ask to store recent snapshots with faster access.

In the hospital example above, the importance and the relative lifetimes of the snapshots

associated with routine procedure

are likely to be known in advance, so

the hospital application can specify a snapshot discrimination policy eagerly.

4.1 Eager ranked segregation

The eager ranked segregation protocol provides efficient

discrimination for eager rank-tree policies.

The protocol assigns a separate archive region

to hold the snapshot pages ( ) and snapshot page tables (VPT

) and snapshot page tables (VPT ) for snapshots at level

) for snapshots at level  .

During snapshot creation, the protocol segregates the different lifetime

pages and copies them into the corresponding regions. This way,

each region contains pages and page tables with the same lifetime

and temporal reclamation of snapshots (satisfying policy property RT2) within

a region does not create disk fragmentation. Figure 3 shows a segregated archive.

.

During snapshot creation, the protocol segregates the different lifetime

pages and copies them into the corresponding regions. This way,

each region contains pages and page tables with the same lifetime

and temporal reclamation of snapshots (satisfying policy property RT2) within

a region does not create disk fragmentation. Figure 3 shows a segregated archive.

At each rank level  , snapshots ranked at level

, snapshots ranked at level  are archived in the same incremental manner

as in SNAP and at the same low sequential cost.

The cost is low because by using sufficiently large write buffers (one for each volume),

archiving to multiple volumes

can be as efficient as strictly sequential archiving into one volume.

Since we expect the rank-tree to be quite shallow

the total amount of memory allocated to write buffers is small.

are archived in the same incremental manner

as in SNAP and at the same low sequential cost.

The cost is low because by using sufficiently large write buffers (one for each volume),

archiving to multiple volumes

can be as efficient as strictly sequential archiving into one volume.

Since we expect the rank-tree to be quite shallow

the total amount of memory allocated to write buffers is small.

The eager ranked segregation works as follows.

The declaration of a

snapshot  with a rank specified at level

with a rank specified at level  , creates

a separate incremental snapshot page table, VPT

, creates

a separate incremental snapshot page table, VPT for every rank level

for every rank level  .

.

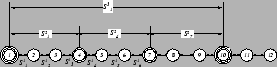

Figure 4:

Example rank-tree policy

|

The incremental page table VPT collects the mappings for the pages recorded by snapshot

collects the mappings for the pages recorded by snapshot  at level

at level  .

Since the incremental tables in VPT

.

Since the incremental tables in VPT map the pages recorded by all the snapshots

at level

map the pages recorded by all the snapshots

at level  , the basic snapshot page table reconstruction protocol based on a forward scan

through VPT

, the basic snapshot page table reconstruction protocol based on a forward scan

through VPT (Section 3.2)

can be used in region

(Section 3.2)

can be used in region  to reconstruct snapshot tables for level

to reconstruct snapshot tables for level  snapshots.

snapshots.

The recorded pages contain the pre-state before the first page modification in the snapshot span.

Since the span for snapshot  at

level

at

level  (denoted

(denoted  )

includes the spans of all the lower level snapshots declared during

)

includes the spans of all the lower level snapshots declared during  ,

pages recorded by a level

,

pages recorded by a level  snapshot

snapshot  are also

recorded by some of these lower-ranked snapshots.

In Figure 4,

the span of snapshot 4 ranked at level 2 includes the spans of

snapshots (4), 5 and 6 at level 1.

Therefore, a page recorded by the snapshot 4 at level 2 is also recorded by one of the snapshots (4), 5, or 6

at level 1.

are also

recorded by some of these lower-ranked snapshots.

In Figure 4,

the span of snapshot 4 ranked at level 2 includes the spans of

snapshots (4), 5 and 6 at level 1.

Therefore, a page recorded by the snapshot 4 at level 2 is also recorded by one of the snapshots (4), 5, or 6

at level 1.

A page  recorded by snapshots at multiple levels

is archived in the volume of the highest-ranked snapshot that records

recorded by snapshots at multiple levels

is archived in the volume of the highest-ranked snapshot that records  .

We say that the highest recorder captures

.

We say that the highest recorder captures  .

Segregating archived pages this way guarantees that

a volume of the shorter-lived snapshots contains no longer-lived pages

and therefore temporal reclamation within a volume creates no fragmentation.

.

Segregating archived pages this way guarantees that

a volume of the shorter-lived snapshots contains no longer-lived pages

and therefore temporal reclamation within a volume creates no fragmentation.

The mappings in a snapshot page table VPT in area

in area  point to the pages recorded by snapshot

point to the pages recorded by snapshot  in whatever

area these pages are archived.

Snapshot reclamation needs to insure

that the snapshot page table mappings are safe, that is, they do not point to reclaimed pages.

The segregation protocol guarantees the safety of the snapshot page table mappings

by enforcing the following invariant

in whatever

area these pages are archived.

Snapshot reclamation needs to insure

that the snapshot page table mappings are safe, that is, they do not point to reclaimed pages.

The segregation protocol guarantees the safety of the snapshot page table mappings

by enforcing the following invariant  that

constrains the intra-level and inter-level reclamation order for snapshot pages and page tables:

that

constrains the intra-level and inter-level reclamation order for snapshot pages and page tables:

and the pages recorded by snapshot

and the pages recorded by snapshot  that are captured in

that are captured in  are reclaimed together,

in temporal snapshot order.

are reclaimed together,

in temporal snapshot order.

- Pages recorded by snapshot

at level

at level  , captured in

, captured in  , are reclaimed after

the pages recorded by all level

, are reclaimed after

the pages recorded by all level  snapshots declared in the span of snapshot

snapshots declared in the span of snapshot  at level

at level  .

.

I(1) insures that in each given rank-tree level, the snapshot page table mappings are safe when

they point to pages captured in volumes within the same level.

I(2) insures that the snapshot page table mappings are

safe when they point to pages captured in volumes above their level.

Note that the rank-tree policy property RT2 only requires that

``bumping up'' a lower-ranked snapshot  to level

to level  extends its lifetime but it

does not constrain the lifetimes of the lower-level snapshots

declared in the span of

extends its lifetime but it

does not constrain the lifetimes of the lower-level snapshots

declared in the span of  at level

at level  .

I(2) insures the safety of the snapshot table mappings for these later lower-level snapshots.

.

I(2) insures the safety of the snapshot table mappings for these later lower-level snapshots.

Figure 5:

Eager ranked segregation

|

Figure 5 depicts

the eager segregation protocol for a two-level rank-tree policy shown in the figure.

Snapshot  , specified at level

, specified at level  , has a snapshot page table at both level

, has a snapshot page table at both level  and level

and level  .

The archived page

.

The archived page  modified within the span of snapshot

modified within the span of snapshot  , is recorded by snapshot

, is recorded by snapshot  ,

and also by the level

,

and also by the level  snapshot

snapshot  .

This version of

.

This version of  is archived in the volume of the highest recording snapshot (denoted

is archived in the volume of the highest recording snapshot (denoted  ).

The snapshot page tables of both recording snapshots

).

The snapshot page tables of both recording snapshots  and

and  contain this mapping for

contain this mapping for  .

Similarly, the pre-state of page

.

Similarly, the pre-state of page  modified within the span of

modified within the span of  is also captured

in

is also captured

in  .

.

is modified again within the span of snapshot

is modified again within the span of snapshot  .

This later version of P is not recorded by snapshot

.

This later version of P is not recorded by snapshot  at level

at level  since

since  has already recorded its version of

has already recorded its version of  .

This later version of

.

This later version of  is archived in

is archived in  and its mapping

is inserted into VPT

and its mapping

is inserted into VPT .

Invariant

.

Invariant  guarantees that in VPT

guarantees that in VPT mappings for page

mappings for page  in

in  is safe.

Invariant

is safe.

Invariant  guarantees that in VPT

guarantees that in VPT the mapping for page

the mapping for page  in volume

in volume  is safe.

is safe.

4.2 Lazy segregation

Some applications may need to defer snapshot ranking

to after the snapshot has already been declared

(use a lazy rank-tree policy).

When snapshots are archived first and ranked later, snapshot discrimination

can be costly because it requires copying.

The lazy segregation protocol provides efficient lazy discimination

by combining two techniques to reduce the cost of copying.

First, it uses a more compact diff-based representation for snapshot pages

so that there is less to copy.

Second, the diff-based representation (as explained below) includes a component that has

a page-based snapshot representation.

This page-based component is segregated without copying using the eager segregation protocol.

The compact diff-based representation implements the same abstraction

of snapshot pages and snapshot page tables, as the page-based snapshot representation.

It is similar to database redo recovery log

consisting of sequential repetitions of two types of components, checkpoints and diffs.

The checkpoints are incremental page-based snapshots declared periodically by the storage

management system. The diffs are versioned

page diffs, consisting of versioned object modifications clustered by page.

Since typically only a small fraction

of objects in a page is modified by a transaction, and moreover,

many attributes do not change, we expect the diffs to be compact.

The log repetitions containing the diffs and the checkpoints are

archived sequentially, with diffs and checkpoints written into different archive data structures.

Like in SNAP, the incremental snapshot page tables collect the archived page mappings

for the checkpoint snapshots.

A simple page index structure

keeps track of page-diffs in each log repetition (the diffs in one log repetition are referred to as diff extent).

To create the diff-based representation, the cleaner sorts

the diffs in an in-memory buffer, assembling the page-based diffs for the diff extents.

The available sorting buffer size determines the length of diff extents.

Since frequent checkpoints decrease the compactness of the diff-based

representation, to get better compactness, the cleaner may create several diff extents in a single log repetition.

Increasing the number of diff extents slows down BITE.

This trade-off is similar to the recovery log.

For brevity, we omit the details

of how the diff-based representation is constructed.

The details can be found in [16].

The performance section discusses some of

the issues related to the diff-based representation compactness that

are relevant to the snapshot storage management performance.

The snapshots declared between

checkpoints are reconstructed by first mounting the snapshot page table

for the closest (referred to as

base) checkpoint and the corresponding diff-page index.

This allows BITE

to access the checkpoint pages, and the

corresponding page-diffs.

To reconstruct  , the version of

, the version of  in snapshot

in snapshot  ,

the server reads page

,

the server reads page  from the checkpoint,

and then reads in order, the diff-pages for

from the checkpoint,

and then reads in order, the diff-pages for  from all the

needed diff extents and applies them to the checkpoint

from all the

needed diff extents and applies them to the checkpoint  in order.

in order.

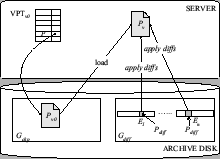

Figure 6:

BITE: diff-based representation

|

Figure 6

shows an example of reconstructing a page  in a diff-based snapshot

in a diff-based snapshot  from

a checkpoint page

from

a checkpoint page  and diff-pages contained in several diff extents.

and diff-pages contained in several diff extents.

When an application eventually provides a snapshot ranking,

the system simply reads back the archived diff extents,

assembles the diff extents for the longer-lived snapshots, creates the

corresponding long-lived base checkpoints,

and archives the retained snapshots sequentially into a longer-lived area.

If diffs are compact, the cost of copying is low.

The long-lived base checkpoints are created without copying

by separating the long-lived

and short-lived checkpoint pages using eager segregation.

Since checkpoints are simply page-based snapshots declared periodically

by the system, the system can derive the ranks for the base checkpoints

once the application specifies the snapshot ranks.

Knowing ranks at checkpoint declaration time

enables eager segregation.

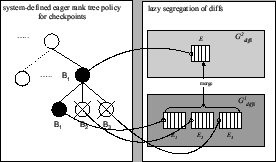

Figure 7:

Lazy segregation

|

Consider two adjacent log repetitions  ,

,  for level-

for level- snapshots,

with

corresponding base checkpoints

snapshots,

with

corresponding base checkpoints  , and

, and  . Suppose

the base checkpoint

. Suppose

the base checkpoint  is to be reclaimed when the adjacent level-

is to be reclaimed when the adjacent level- diff extents

are merged into one level

diff extents

are merged into one level  diff extent.

Declaring the base checkpoint

diff extent.

Declaring the base checkpoint  a level-

a level- rank tree snapshot, and base checkpoint

rank tree snapshot, and base checkpoint  as level-

as level- rank tree snapshot, allows to reclaim the pages of

rank tree snapshot, allows to reclaim the pages of  without fragmentation or copying.

without fragmentation or copying.

Figure 7 shows an example eager rank-tree policy for checkpoints in lazy segregation.

A representation for level- snapshots

has the diff extents

snapshots

has the diff extents  ,

,  and

and  (in the

archive region

(in the

archive region  ) associated with the base checkpoints

) associated with the base checkpoints  ,

,  and

and  .

To create the level-

.

To create the level- snapshots,

snapshots,  ,

,  and

and  are merged into extent

are merged into extent  (in region

(in region  ).

This extent

).

This extent  has a base checkpoint

has a base checkpoint  . Eventually, extents

. Eventually, extents  ,

,  ,

,  and

checkpoints

and

checkpoints  ,

,  are reclaimed. Since

are reclaimed. Since  was ranked at declaration time as rank-2

longer-lived snapshot, the eager segregation protocol lets

was ranked at declaration time as rank-2

longer-lived snapshot, the eager segregation protocol lets  capture all the checkpoint pages it records,

allowing to reclaim the shorter-lived pages of

capture all the checkpoint pages it records,

allowing to reclaim the shorter-lived pages of  and

and  without fragmentation.

without fragmentation.

Our lazy segregation protocol is optimized for the case where the application

specifies snapshot rank within a limited time period after snapshot declaration, which we expect to be the common case.

If the limit is exceeded, the system reclaims shorter-lived

base checkpoints by copying out longer-lived pages at a much higher cost.

The same approach can also be used if the application needs to change the discrimination policy.

4.3 Faster BITE

The diff-based representation is more compact

but has a slower BITE than the page-based representation.

Some applications require lazy discrimination

but also need low-latency BITE on a recent window of snapshots.

For example, to examine the recent snapshots

and identify the ones to be retained.

The eager segregation protocol allows efficient composition of diff-based and

page-based representations

to provide fast BITE on recent snapshots,

and lazy snapshot discrimination.

The composed representation, called hybrid, works as follows.

When an application declares a snapshot,

hybrid creates two snapshot representations. A page-based representation is created

in a separate archive region that maintains a sliding window

of  recent snapshots, reclaimed temporally.

BITE on snapshots within

recent snapshots, reclaimed temporally.

BITE on snapshots within  runs on the fast page-based representation.

In addition, to enable efficient lazy discrimination, hybrid creates

for the snapshots a diff-based representation.

BITE on snapshots outside

runs on the fast page-based representation.

In addition, to enable efficient lazy discrimination, hybrid creates

for the snapshots a diff-based representation.

BITE on snapshots outside  runs on the slower diff-based representation.

Snapshots within

runs on the slower diff-based representation.

Snapshots within  therefore have two

representations (page-based and diff-based).

therefore have two

representations (page-based and diff-based).

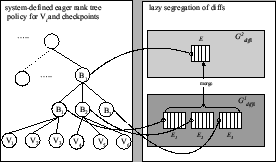

Figure 8:

Reclamation in Hybrid

|

The eager segregation protocol can be used to efficiently compose the two representations

and provide efficient reclamation.

To achieve the efficient composition, the system specifies

an eager rank-tree policy that ranks the page-based snapshots

as lowest-rank (level- ) rank-tree snapshots, but specifies the ones that correspond to

the system-declared checkpoints in the diff-based representation, as level-

) rank-tree snapshots, but specifies the ones that correspond to

the system-declared checkpoints in the diff-based representation, as level- .

As in lazy segregation, the checkpoints can be further discriminated by bumping up the rank of the longer-lived checkpoints.

With such eager policy, the eager segregation protocol can retain the snapshots declared by the system as checkpoints

without copying, and can reclaim the aged snapshots

in the page-based window

.

As in lazy segregation, the checkpoints can be further discriminated by bumping up the rank of the longer-lived checkpoints.

With such eager policy, the eager segregation protocol can retain the snapshots declared by the system as checkpoints

without copying, and can reclaim the aged snapshots

in the page-based window  without fragmentation.

The cost of checkpoint creation and segregation is completely absorbed into the cost

of creating the page-based snapshots, resulting in lower archiving cost than

the simple sum of the two representations.

without fragmentation.

The cost of checkpoint creation and segregation is completely absorbed into the cost

of creating the page-based snapshots, resulting in lower archiving cost than

the simple sum of the two representations.

Figure 8 shows reclamation in the hybrid system

that adds faster BITE to the snapshots in Figure 7.

The system creates the page-based snapshots  and uses them to run fast BITE on recent snapshots.

Snapshots

and uses them to run fast BITE on recent snapshots.

Snapshots  and

and  are used as base checkpoints

are used as base checkpoints  and

and  for the diff-based representation, and

checkpoint

for the diff-based representation, and

checkpoint  is retained as a longer-lived chekpoint.

The system specifies an eager rank-tree policy, ranking snapshots

is retained as a longer-lived chekpoint.

The system specifies an eager rank-tree policy, ranking snapshots  at level-

at level- , and bumping up

, and bumping up  to level-

to level- and

and  to level-

to level- .

This allows the eager segregation protocol to create the checkpoints

.

This allows the eager segregation protocol to create the checkpoints  , and

, and  ,

and eventually reclaim

,

and eventually reclaim  ,

,  and

and  without copying.

without copying.

5 Performance

Efficient discrimination should not increase significantly the cost of snapshots.

We analyze our discrimination techniques under a range of workloads

and show they have minimal impact on the snapshot system performance.

Section 6 presents

the results of our experiments.

This section explains our evaluation approach.

The metric  [12] captures the non-disruptiveness of an I/O-bound storage system.

We use this metric to gauge the impact of snapshot discrimination.

Let

[12] captures the non-disruptiveness of an I/O-bound storage system.

We use this metric to gauge the impact of snapshot discrimination.

Let  be the ``pouring rate'' - average object

cache (MOB/VMOB) free-space consumption speed due to incoming

transaction commits, which insert modified objects.

Let

be the ``pouring rate'' - average object

cache (MOB/VMOB) free-space consumption speed due to incoming

transaction commits, which insert modified objects.

Let  be the ``draining rate'' - the average growth

rate of object cache free space produced by MOB/VMOB cleaning.

We define:

be the ``draining rate'' - the average growth

rate of object cache free space produced by MOB/VMOB cleaning.

We define:

indicates how well the draining keeps up with the pouring.

If

indicates how well the draining keeps up with the pouring.

If

,

the system operates within its capacity

and the foreground transaction performance is not be affected by background

cleaning activities.

If

,

the system operates within its capacity

and the foreground transaction performance is not be affected by background

cleaning activities.

If

, the system is overloaded,

transaction commits eventually block on free object cache space,

and clients experience commit delay.

, the system is overloaded,

transaction commits eventually block on free object cache space,

and clients experience commit delay.

Let  be the average cleaning time

per dirty database page. Apparently,

be the average cleaning time

per dirty database page. Apparently,

determines

determines  .

In Thresher,

.

In Thresher,  reflects, in addition to the database ireads and writes,

the cost of snapshot creation and snapshot discrimination.

Since snapshots are created on a separate disk

in parallel with the database cleaning, the cost of

snapshot-related activity can be partially ``hidden'' behind database

cleaning. Both the update workload,

and the compactness of snapshot representation affect

reflects, in addition to the database ireads and writes,

the cost of snapshot creation and snapshot discrimination.

Since snapshots are created on a separate disk

in parallel with the database cleaning, the cost of

snapshot-related activity can be partially ``hidden'' behind database

cleaning. Both the update workload,

and the compactness of snapshot representation affect  , and determine

how much can be hidden, i.e. non-disruptiveness.

, and determine

how much can be hidden, i.e. non-disruptiveness.

Overwriting ( ) is an update workload parameter, defined as

the percentage of repeated modifications to the same object or page.

) is an update workload parameter, defined as

the percentage of repeated modifications to the same object or page.

affects both

affects both  and

and  .

When overwriting increases, updates

cause less cleaning in the storage system because the object cache (MOB/VMOB) absorbs

repeated modifications, but high frequency

snapshots may need to archive most of the repeated modifications.

With less cleaning, it may be harder to

hide archiving behind cleaning, so snapshots may become more disruptive.

On the other hand,

workloads with repeated modifications reduce the amount of copying when lazy discrimination copies diffs.

For example, for a two-level discrimination policy that

retains one snapshot out of every hundred, of all the

repeated modifications to a given object

.

When overwriting increases, updates

cause less cleaning in the storage system because the object cache (MOB/VMOB) absorbs

repeated modifications, but high frequency

snapshots may need to archive most of the repeated modifications.

With less cleaning, it may be harder to

hide archiving behind cleaning, so snapshots may become more disruptive.

On the other hand,

workloads with repeated modifications reduce the amount of copying when lazy discrimination copies diffs.

For example, for a two-level discrimination policy that

retains one snapshot out of every hundred, of all the

repeated modifications to a given object  , archived for the

short-lived level-1 snapshots, only one (last) modification gets retained in the level-2 snapshots.

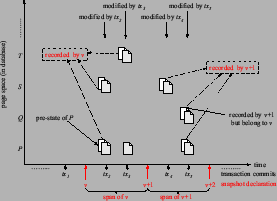

To gage the impact of discrimination on the non-disruptiveness,

we measure

, archived for the

short-lived level-1 snapshots, only one (last) modification gets retained in the level-2 snapshots.

To gage the impact of discrimination on the non-disruptiveness,

we measure  and

and  experimentally in a system with and without

discrimination for a range of workloads with low, medium and high

degree of overwriting, and analyze the resulting

experimentally in a system with and without

discrimination for a range of workloads with low, medium and high

degree of overwriting, and analyze the resulting  .

.

determines the maximum throughput of an I/O bound storage system.

Measuring the maximum throughput in a system with and without discrimination

could provide an end-to-end metric for gauging the impact of discrimination. We focus

on

determines the maximum throughput of an I/O bound storage system.

Measuring the maximum throughput in a system with and without discrimination

could provide an end-to-end metric for gauging the impact of discrimination. We focus

on  because it allows us to explain better the

complex dependency between workload parameters and cost of discrimination.

because it allows us to explain better the

complex dependency between workload parameters and cost of discrimination.

The effectiveness of diff-based representation in reducing copying cost

depends on the compactness of the representation.

We characterize compactness by a relative snapshot retention metric  ,

defined as the size of snapshot state written into the archive

for a given snapshot history length

,

defined as the size of snapshot state written into the archive

for a given snapshot history length  , relative to the size of

the snapshot state for

, relative to the size of

the snapshot state for  captured in full snapshot pages.

captured in full snapshot pages.

for the page-based representation.

for the page-based representation.

of the diff-based representation has two contributing components,

of the diff-based representation has two contributing components,  for the checkpoints, and

for the checkpoints, and  for the diffs.

Density (

for the diffs.

Density ( ), a workload parameter defined as the fraction

of the page that gets modified by an update, determines

), a workload parameter defined as the fraction

of the page that gets modified by an update, determines  .

For example, in a static update workload where any

time a page is updated, the same half of the page gets

modified,

.

For example, in a static update workload where any

time a page is updated, the same half of the page gets

modified,

.

.

depends on the frequency of checkpoints,

determined by

depends on the frequency of checkpoints,

determined by  - the number of snapshots declared in the history interval corresponding to one log repetition.

In workloads with overwriting, increasing

- the number of snapshots declared in the history interval corresponding to one log repetition.

In workloads with overwriting, increasing  decreases

decreases  since checkpoints are

page-based snapshots that record the first pre-state

for each page modified in the log repetition.

Increasing

since checkpoints are

page-based snapshots that record the first pre-state

for each page modified in the log repetition.

Increasing  by increasing

by increasing  , the number of diff extents in a log repetition, raises the

snapshot page reconstruction cost for BITE. Increasing

, the number of diff extents in a log repetition, raises the

snapshot page reconstruction cost for BITE. Increasing  without

increasing

without

increasing  requires additional server memory for the cleaner to sort diffs when assembling

diff pages.

requires additional server memory for the cleaner to sort diffs when assembling

diff pages.

Diff-based representation will not be compact

if transactions modify all the objects in a page.

Common update workloads have sparse modifications because most applications

modify far fewer objects than they read.

We determine the compactness of the diff-based representation

by measuring  and

and  for workloads with expected medium and low update density.

for workloads with expected medium and low update density.

6 Experimental evaluation

Thresher implements in SNAP [12] the techniques

we have described, and also support for recovery during normal operation

without the failure recovery procedure.

This allows us to evaluate system

performance in the absence of failures.

Comparing the performance of Thresher and SNAP

reveals a meaningful snapshot discrimination cost

because SNAP is very efficient: even at high snapshot frequencies

it has low impact on the storage system [12].

6.0.0.1 Workloads.

To study the impact of the workload we

use the standard multiuser OO7 benchmark [2] for object storage systems.

We omit the benchmark definition for lack of space.

An OO7 transaction includes a read-only traversal (T1), or a read-write traversal (T2a or T2b). The traversals T2a and T2b generate workloads with fixed amount of object

overwriting and density. We have implemented extended traversal summarized below that allow us to control these parameters.

To control the degree of overwriting,

we use a variant traversal T2a' [12],

that extends T2a to update a randomly selected AtomicPart

object of a CompositePart instead of always modifying

the same (root) object in T2a.

Like T2a, each T2a' traversal modifies 500 objects.

The desired amount of overwriting is achieved by adjusting

the object update history in a sequence of T2a' traversals.

Workload parameter  controls the amount of overwriting.

Our experiments use three settings for

controls the amount of overwriting.

Our experiments use three settings for  , corresponding

to low (0.08), medium (0.30) and very high (0.50) degree of overwriting.

, corresponding

to low (0.08), medium (0.30) and very high (0.50) degree of overwriting.

To control density, we developed

a variant of traversal T2a', called T2f (also modifies 500 objects),

that allows to determine  , the average number of modified

AtomicPart objects on a dirty page when the dirty page is written back to database

(on average, a page in OO7 has 27 such objects).

Unlike T2a' which modifies

one AtomicPart in the CompositePart,

T2f modifies a group of AtomicPart objects around

the chosen one. Denote by T2f-

, the average number of modified

AtomicPart objects on a dirty page when the dirty page is written back to database

(on average, a page in OO7 has 27 such objects).

Unlike T2a' which modifies

one AtomicPart in the CompositePart,

T2f modifies a group of AtomicPart objects around

the chosen one. Denote by T2f- the workload with group of size g.

T2f-1 is essentially T2a'.

the workload with group of size g.

T2f-1 is essentially T2a'.

The workload density  is controlled by specifying the size of the group.

In addition, since repeated T2f-g traversals update multiple objects on each data

page due to write-absorption provided by MOB,

T2f-g, like T2a', also controls the overwriting between traversals.

We specify the size of the group, and the desired overwriting,

and experimentally determine

is controlled by specifying the size of the group.

In addition, since repeated T2f-g traversals update multiple objects on each data

page due to write-absorption provided by MOB,

T2f-g, like T2a', also controls the overwriting between traversals.

We specify the size of the group, and the desired overwriting,

and experimentally determine  in the resulting workload.

For example,

given 2MB of VMOB (the standard configuration in Thor and SNAP

for single-client workload),

the measured

in the resulting workload.

For example,

given 2MB of VMOB (the standard configuration in Thor and SNAP

for single-client workload),

the measured  of multiple T2f-1 is 7.6

(medium

of multiple T2f-1 is 7.6

(medium  , transaction 50% on private module, 50% on public module).

T2f-180 that modifies almost every AtomicPart in a module, has

, transaction 50% on private module, 50% on public module).

T2f-180 that modifies almost every AtomicPart in a module, has  = 26,

yielding almost the highest possible workload density for OO7 benchmark.

Our experiments use workloads corresponding to three settings of density

= 26,

yielding almost the highest possible workload density for OO7 benchmark.

Our experiments use workloads corresponding to three settings of density  ,

low (T2f-1,

,

low (T2f-1, =7.6), medium (T2f-26,

=7.6), medium (T2f-26, =16)

and very high (T2f-180,

=16)

and very high (T2f-180, =26)

Unless otherwise specified, a medium overwriting rate is being used.

=26)

Unless otherwise specified, a medium overwriting rate is being used.

6.0.0.2 Experimental configuration.

We use two experimental system configurations.

The single-client experiments run with snapshot frequency 1,

declaring a snapshot after each transaction, in a 3-user OO7 database (185MB in size).

The multi-client scalability experiments run with snapshot frequency 10

in a large database (140GB in size).

The size of a single private client module is the same in both configurations.

All the reported results show the mean of at least three trials

with maximum standard deviation at  .

.

The storage system server runs on a Linux (kernel 2.4.20) workstation with

dual 64-bit Xeon 3Ghz CPU, 1GB RAM.

Two Seagate Cheetah disks (model ST3146707LC, 10000 rpm, 4.7ms avg seek, Ultra320 SCSI)

directly attach to the server via LSI Fusion MPT adapter.

The database and the archive reside on separate raw hard disks.

The implementation uses Linux raw devices and direct I/O

to bypass file system cache.

The client(s) run on workstations with single P3 850Mhz CPU and 512MB of RAM.

The clients and server are inter-connected via a 100Mbps switched network.

In single-client experiments, the server is

configured with 18 MB of page cache ( of the database size), and a 2MB MOB in Thor.

In multi-client experiments, the server is configured with 30MB of page cache

and 8-11MB of MOB in Thor.

The snapshot systems are configured with slightly more memory [12] for VMOB

so that the same number of dirty database pages is generated in all

snapshot systems, normalizing the

of the database size), and a 2MB MOB in Thor.

In multi-client experiments, the server is configured with 30MB of page cache

and 8-11MB of MOB in Thor.

The snapshot systems are configured with slightly more memory [12] for VMOB

so that the same number of dirty database pages is generated in all

snapshot systems, normalizing the  comparison to Thor.

comparison to Thor.

6.1 Experimental results

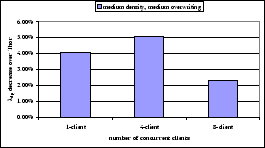

We analyze in turn, the performance of eager segregation,

lazy segregation, hybrid representation, and BITE under a single-client workload,

and then evaluate system scalability under a multiple concurrent client workload.

6.1.1.1 Eager segregation.

Compared to SNAP, the cost of eager discrimination in Thresher

includes the cost of creating VPTs for higher-level snapshots.

Table 1 shows  in Thresher for a two-level eager rank-tree with inter-level retention fraction

fraction

in Thresher for a two-level eager rank-tree with inter-level retention fraction

fraction  set to one snapshot in 200, 400, 800, and 1600.

set to one snapshot in 200, 400, 800, and 1600.

Table 1:

: eager segregation

: eager segregation

| f |

200 |

400 |

800 |

1600 |

|

5.08ms |

5.07ms |

5.10ms |

5.08ms |

The  in SNAP is 5.07ms.

Not surprisingly, the results

show no noticeable change, regardless of retention fraction.

The small incremental page tables contribute a very small fraction (0.02% to 0.14% ) of the overall

archiving cost even for the lowest-level snapshots, rendering eager segregation essentially free of cost.

This result is important, because

eager segregation is used to reduce the cost of lazy segregation and hybrid representation.

in SNAP is 5.07ms.

Not surprisingly, the results

show no noticeable change, regardless of retention fraction.

The small incremental page tables contribute a very small fraction (0.02% to 0.14% ) of the overall

archiving cost even for the lowest-level snapshots, rendering eager segregation essentially free of cost.

This result is important, because

eager segregation is used to reduce the cost of lazy segregation and hybrid representation.

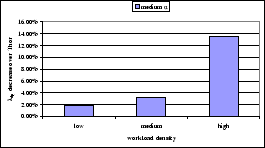

6.1.1.2 Lazy segregation.

We analyzed the cost of lazy segregation for a 2-level rank-tree by comparing the cleaning costs,

and the resulting  in four different system configurations,

Thresher with lazily segregated diff-based snapshots (``Lazy''),

Thresher with unsegregated diff-based snapshots (``Diff''), page-based (unsegregated) snapshots(``SNAP''), and

storage system without snapshots (``Thor''), under

workloads with a wide range of density and overwriting parameters.

in four different system configurations,

Thresher with lazily segregated diff-based snapshots (``Lazy''),

Thresher with unsegregated diff-based snapshots (``Diff''), page-based (unsegregated) snapshots(``SNAP''), and

storage system without snapshots (``Thor''), under

workloads with a wide range of density and overwriting parameters.

Table 2:

Lazy segregation and overwriting

|

|

|

|

|

| low |

|

|

|

|

| |

Lazy |

5.30ms |

0.13ms |

2.24 |

| |

Diff |

5.28ms |

0.08ms |

2.26 |

| |

SNAP |

5.37ms |

|

2.24 |

| |

Thor |

5.22ms |

|

2.30 |

| medium |

|

|

|

|

| |

Lazy |

4.98ms |

0.15ms |

3.67 |

| |

Diff |

5.02ms |

0.10ms |

3.69 |

| |

SNAP |

5.07ms |

|

3.72 |

| |

Thor |

4.98ms |

|

3.79 |

| high |

|

|

|

|

| |

Lazy |

4.80ms |

0.21ms |

4.58 |

| |

Diff |

4.80ms |

0.14ms |

4.66 |

| |

SNAP |

4.87ms |

|

4.61 |

| |

Thor |

4.61ms |

|

4.83 |

The complete results, omitted

for lack of space, can be found in [16].

Here we focus on the low and medium overwriting and density parameter values we expect to be more common.

A key factor affecting the cleaning costs in the diff-based systems

is the compactness of the diff-based representation.

A diff-based system configured

with a 4MB sorting buffer,

with medium overwriting,

has a very low

(0.5% - 2%) for the low density workload (

(0.5% - 2%) for the low density workload ( is 0.3%).

For medium density workload (

is 0.3%).

For medium density workload ( is 3.7%),

the larger diffs fill sorting buffer faster but

is 3.7%),

the larger diffs fill sorting buffer faster but

decreases from 10.1% to 4.8% when

decreases from 10.1% to 4.8% when  increases

from 2 to 4 diff extents.

These results point to the space saving benefits offered by the diff-based representation.

increases

from 2 to 4 diff extents.

These results point to the space saving benefits offered by the diff-based representation.

Table 2 shows the cleaning costs and  for all four systems

for medium density workload with low, medium, and high overwriting.

The

for all four systems

for medium density workload with low, medium, and high overwriting.

The  measured in the Lazy and Diff systems includes the database