Ari Juels

RSA Laboratories1

ajuels@rsa.com

Sid Stamm

Indiana University, Bloomington

sstamm@indiana.edu

Markus Jakobsson

Indiana University, Bloomington and RavenWhite Inc.

markus@indiana.edu

Key words:

authentication, click-fraud

A syndicator or publisher's server observes a ``click'' simply as a browser request for a URL associated with a particular ad. The server has no way to determine if a human initiated the action--and, if a human was involved, whether she acted knowingly and with honest intent. Syndicators typically seek to filter fraudulent or spurious clicks based on information such as the type of advertisement that was requested, the cost of the associated keyword, the IP address of the request and the recent number of requests from this address. In this paper, we propose an alternative approach. Rather than seeking to detect and eliminate fraudulent clicks, i.e., filtering out seemingly bad clicks, we consider ways of authenticating valid clicks, i.e., admitting only verifiably good ones. We refer to such validated clicks as premium clicks.

Our scheme involves a new entity, referred to as an attestor, that provides cryptographic credentials for clients that perform qualifying actions, such as purchases. These credentials allow the syndicator to distinguish premium clicks-corresponding to relatively low-risk clients-from other, general click traffic. Such classification of clicks strengthens a syndicator's heuristic isolation of fraud risks.

The premium-click techniques that we describe in this paper are complementary to existing, filter-based tools for validating clicks: The two approaches can can operate side by side.

Click-fraud is a type of abuse that exploits the lack of verifiable human engagement in PPC requests in order to fabricate ad traffic. It can take a number of forms. One virulent, automated type of click fraud involves a client that fraudulently simulates a click by means of a script or bot--or as the result of infection by a virus or Trojan. Such malware typically resides on the computer of the user from which the click will be generated, but can also in principle reside on access points and consumer routers [8,9,7]. Some click-fraud relies on real clicks, whether intentional or not. An example of the former is a so-called click-farm, which is a term denoting a group of low-wage workers who click for a living; another example involves deceiving or convincing users to click on advertisements. An example of an unintentional click is one generated by a malicious cursor-following script that places the banner right under the mouse cursor [6]. This can be done in a very small window to avoid detection. When the user clicks, the click would be interpreted as a click on the banner, and cause revenue generation to the attacker. A related abuse is manifested in an attack where publishers manipulate web pages such that honest visitors inadvertently trigger clicks [4]. This can be done for many common PPC schemes, and simply relies on the inclusion of a JavaScript component on the publisher's webpage, where the script reads the banner and performs a get request that corresponds to what would be performed if a user had initiated a click.

Click fraud can benefit a fraudster in at least three known ways: First of all, a fraudster can use click-fraud to inflate the revenue of a publisher. Second, a fraudster can employ click-fraud to inflate advertising costs for a commercial competitor. As advertisers generally specify caps on their daily advertising expenses, such fraud is essentially a denial-of-service attack. Third, a fraudster can modify the ranking of advertisements by a combination of impressions and clicks. An impression is the viewing of the banner, with no click; this causes the ranking of the associated advertisement to go down. This can be done to benefit own advertising programs at the cost of those of competitors, and to manipulate the price paid per click for selected keywords.

Syndicators can in principle derive financial benefit from click fraud in the short term, as they receive revenue for whatever clicks they deem ``valid.'' In the long term, however, as customers become sensitive to losses, and syndicators rely on third-party auditors to lend credibility to their operations, click fraud can jeopardize syndicator-adverstiser relationships. Thus syndicators ultimately have a strong incentive to eliminate fraudulent clicks. Today they employ a battery of filters to weed out suspicious clicks. These filters are trade secrets, as their disclosure might prompt new forms of fraud [10]. To give one example, though, it is likely that syndicators use IP tracing to determine if an implausible number of clicks is originating from a single source. While heuristic filters are fairly effective, they are of limited utility against sophisticated fraudsters, and subject to degraded performance as fraudsters learn to defeat them.

Our premium-click scheme has two distinctive aspects:

Under the model of premium clicks, there are additional tasks carried out: As a user performs a qualified action (such as a purchase), the corresponding attestation is embedded in his browser by an attestor. This attestation is released to the syndicator when the user clicks on a banner. The release can be initiated either by the syndicator or the advertiser. (Our prototype relies on syndicator triggering of coupon release.) The syndicator can pay attestors for their participation in a number of ways, ranging from a flat fee per time period to a payment that depends on the number of associated attestations that were recorded in a time interval. To avoid a situation where dishonest attestors issue larger number of attestations than the protocol prescribes (which would increase the earnings of the dishonest attestors), it is possible to appeal to standard auditing techniques.

Of course, our techniques do not prevent misuse of coupons by clients that are ``good,'' i.e., controlled by honest users, and then turn ``bad,'' e.g., become infected with malware. By identifying the sources of clicks, however, and making traffic caps more effective, coupons in our scheme still offer some protection against fraud even in such cases.

It is important to observe that existing filtering methods cannot in general employ cookies/coupons to detect fraudulent clicks. That is because filtering is an exclusionary process: It seeks to identify and eliminate ``bad'' clicks. If a cookie were used to mark and exclude certain types of ``bad'' users, fraudsters could simply remove the cookies from their browsers. In contrast, because our premium-click scheme is distinguishing, i.e., it only accepts ``good'' clicks, it can benefit from the use of cookies/coupons. Cookies serve to mark ``good'' users.

In a world of perfect transparency, in which a syndicator knew the (real-world) identity of all users clicking on ads, click fraud would be much more manageable. In such a world, it would be easier to identify misbehavior by a real user--e.g., implausibly many clicks--as well as clicks initiated by bogus users or bots. A syndicator could go further, and reference databases containing profiles on the users who clicked on its published ads. The syndicator could even create a highly refined pricing structure based on a user's predicted value as a potential consumer, with differential compensation for publishers. Our premium-click protocol diverges from this ideal in two senses:

We design our premium-click scheme to support outsourced PPC

advertising. It can equally well secure against click fraud when ads

are published directly on search engines: We need simply treat the

syndicator and publisher as the same entity.

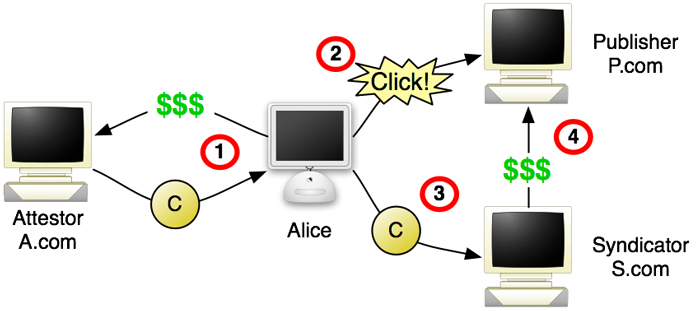

The steps in our scheme are as follows and are illustrated in

Figure 1. For simplicity, we assume a single

syndicator ![]() and attestor

and attestor ![]() . (We discuss the case of

multiple attestors in the appendix.)

. (We discuss the case of

multiple attestors in the appendix.)

|

Of course, the publisher might embed additional information in ![]() ,

e.g.,

a timestamp, etc. Moreover, a user's browser might in fact contain

multiple coupons

,

e.g.,

a timestamp, etc. Moreover, a user's browser might in fact contain

multiple coupons

![]() from different

attestors, a possibility that we discuss below. A single computer may

have multiple users, of course. If they each maintain a separate

account, then their individual browser instantiations will carry

user-specific coupons. When users share a browser, the browser may

carry coupons if at least one of the users is validated by an

attestor. While validation is not user-specific in this case, it is

still helpful: A shared machine with a valid user is considerably more

likely to see honest use than one without.

from different

attestors, a possibility that we discuss below. A single computer may

have multiple users, of course. If they each maintain a separate

account, then their individual browser instantiations will carry

user-specific coupons. When users share a browser, the browser may

carry coupons if at least one of the users is validated by an

attestor. While validation is not user-specific in this case, it is

still helpful: A shared machine with a valid user is considerably more

likely to see honest use than one without.

We now detail the technical foundations of our scheme. We assume here that the browser of a given user carries at most one coupon. We address the case of multiple coupons in the appendix.

Our first technical design choice is the transport medium for coupons. To ensure its correct association with the browser that created it, a coupon is best communicated as a cached browser value (rather than through a back channel). At the same time, it is important to ensure that coupons be set such that only the syndicator can retrieve them, and fraudsters cannot easily harvest them.

Third-party cookies are the most obvious way to instantiate coupons. A third-party cookie is one set for a domain other than the one being visited by the user; thus, a coupon could be set as a third-party cookie. Because third-party cookies have a history of abusive application, however, users regularly block them. First-party cookies are an alternative mechanism. If an attestor redirects users to the site of a syndicator and provides user-specific or session-specific information in the redirection, then the syndicator can implant a coupon in the form of a first-party cookie for its own, later use. Redirection of this kind, however, can be cumbersome, particularly if an attestor has relationships with multiple syndicators.

Cache cookies [5], particularly the TIF-based variety, offer an attractive alternative. An attestor can embed a coupon in a cache-cookie that is tagged for the site of a syndicator, i.e., exclusively readable by the syndicator. In their ability to be set for third-party sites, cache cookies are similar in functionality to third-party cookies. Cache cookies have a special, useful quirk, though: Any Web site visited by a user can cause them to be released to the site for which they are tagged. (Thus, as we shall see, it is important to authenticate the site initiating their release from a user's browser.) Cache cookies, moreover, function even in browsers where ordinary cookies have been blocked. Cache cookies are therefore our preferred medium for coupons.

Briefly, a TIF-based cache cookie works as follows. Suppose we wish to

set a cache cookie bearing value ![]() for release to Web site

www.S.com. The cache cookie, then, assumes the form of an HTML

page ABC.html that requests a resource from www.S.com bearing the

value

for release to Web site

www.S.com. The cache cookie, then, assumes the form of an HTML

page ABC.html that requests a resource from www.S.com bearing the

value ![]() . For example, ABC.html might display a GIF image of the

form http://www.S.com/

. For example, ABC.html might display a GIF image of the

form http://www.S.com/![]() .gif. Observe that any Web

site can create ABC.html and plant it in a visiting user's

browser. Similarly any Web site that knows the name of the

page/cache-cookie ABC.html can reference it, causing www.S.com to

receive a request for

.gif. Observe that any Web

site can create ABC.html and plant it in a visiting user's

browser. Similarly any Web site that knows the name of the

page/cache-cookie ABC.html can reference it, causing www.S.com to

receive a request for ![]() .gif. Only www.S.com, however, can

receive the cache cookie, i.e., the value

.gif. Only www.S.com, however, can

receive the cache cookie, i.e., the value ![]() , when it is

released from the browser.

, when it is

released from the browser.

Ensuring against fraudulent creation or use of coupons is a key challenge in our scheme. Only attestors should be able to construct valid coupons. Coupons must therefore carry a form of cryptographic authentication. While digital signatures can in principle offer a flexible way to authenticate coupons, their computational costs are probably prohibitively expensive for a high-traffic, potentially multi-site scheme of the type we propose here. Message-authentication codes (MACs), a symmetric-key analog of digital signatures, are a more practical alternative.3

Suppose that the attestor ![]() and syndicator

and syndicator ![]() share a

symmetric key

share a

symmetric key ![]() . (This key may be established out of band or using

existing secure channels.) Let

. (This key may be established out of band or using

existing secure channels.) Let ![]() represent a strong message

authentication code, e.g., HMAC [2], computed on a

suitably formed message

represent a strong message

authentication code, e.g., HMAC [2], computed on a

suitably formed message ![]() . It is infeasible for any third party,

e.g., an adversary, to generate a fresh MAC on any message

. It is infeasible for any third party,

e.g., an adversary, to generate a fresh MAC on any message

![]() . Consequently, if a coupon assumes the form

. Consequently, if a coupon assumes the form

![]() for a bitstring

for a bitstring ![]() that is unique to the visit of a

client to the site of an attestor, then the coupon can be copied, but

cannot be feasibly modified by a third party. The value

that is unique to the visit of a

client to the site of an attestor, then the coupon can be copied, but

cannot be feasibly modified by a third party. The value ![]() might be a

suitably long (say, 128-bit) random nonce generated by

might be a

suitably long (say, 128-bit) random nonce generated by ![]() . We

propose some privacy-protecting alternative formats for

. We

propose some privacy-protecting alternative formats for ![]() below.

below.

In addition to ensuring that a coupon is authentic, a syndicator must

also be able to determine what publisher caused it to be released and

is to receive payment for the associated click. Recall from above that

a coupon takes the form

![]() , where

, where

![]() is the identity of the publisher and

is the identity of the publisher and ![]() identifies

the advertisement clicked. In order to create a full coupon, we must

append

identifies

the advertisement clicked. In order to create a full coupon, we must

append ![]() and

and ![]() to

to ![]() as it is

released. To do so, we can enhance a cache cookie webpage X.html to

include the document referrer, i.e., the tag that identifies the

webpage that causes its release.

(In our scheme, this webpage is a URL on the syndicator,

www.S.com, where both

as it is

released. To do so, we can enhance a cache cookie webpage X.html to

include the document referrer, i.e., the tag that identifies the

webpage that causes its release.

(In our scheme, this webpage is a URL on the syndicator,

www.S.com, where both ![]() and

and ![]() are in the URL.)

For example, X.html might take

the following form:

are in the URL.)

For example, X.html might take

the following form:

<html><body>

<script language="JavaScript">

//Determine referring webpage r

// (URL contains ![]() and

and ![]() ):

):

var r = escape(document.referrer);

//Write HTML to release the coupon ![]() .gif:

.gif:

document.write('<img src="http://S.com/'

+ '![]() .gif?ref=' + r + '"/>');

.gif?ref=' + r + '"/>');

</script> </body> </html>

Now when the syndicator's site page with a URL containing

![]() and

and ![]() references X.html, the syndicator www.S.com receives a request for the resource

references X.html, the syndicator www.S.com receives a request for the resource

![]() .gif?ref=www.S.com%3fad%3d

.gif?ref=www.S.com%3fad%3d

![]() %26pub%3d

%26pub%3d

![]() (the value of the ref querystring variable in this resource request is the referrer, or page that triggered X.html to load, but encoded so it can appear in the URL). In essence, he receives a request for an image

(the value of the ref querystring variable in this resource request is the referrer, or page that triggered X.html to load, but encoded so it can appear in the URL). In essence, he receives a request for an image ![]() .gif, and is provided one querystring-style parameter containing the IDs of the advertisement and publisher.

This string conveys the full desired coupon data

.gif, and is provided one querystring-style parameter containing the IDs of the advertisement and publisher.

This string conveys the full desired coupon data

![]() .

.

Authentication alone is insufficient to guarantee valid coupon use. It is also imperative to confirm that a coupon is fresh, that is, that a client is not replaying it more rapidly than justified by ordinary use.

To ensure coupon freshness, a syndicator may maintain a data structure

![]() recording coupons received within a

recent period of time (as determined by syndicator policy). A record

recording coupons received within a

recent period of time (as determined by syndicator policy). A record

![]() can include an authentication value

can include an authentication value ![]() ,

publisher identity

,

publisher identity

![]() , ad identifier

, ad identifier ![]() ,

and a time of coupon receipt

,

and a time of coupon receipt ![]() .

.

When a new coupon

![]() is received at

time

is received at

time ![]() , the syndicator can check whether there exists a

, the syndicator can check whether there exists a

![]() with time-stamp

with time-stamp ![]() . If

. If

![]() , for some system parameter

, for some system parameter ![]() determined by syndicator policy, then the syndicator might reject

determined by syndicator policy, then the syndicator might reject ![]() as a replay. Similarly, the syndicator can set replay windows for

cross-domain and cross-advertisement clicks. For example, if

as a replay. Similarly, the syndicator can set replay windows for

cross-domain and cross-advertisement clicks. For example, if

![]() , where

, where

![]() , i.e., it appears that a given user has clicked on a

different ad on the same site as that represented by

, i.e., it appears that a given user has clicked on a

different ad on the same site as that represented by ![]() , the

syndicator might implement a different check

, the

syndicator might implement a different check

![]() to determine that a coupon is stale and should be

rejected. Since a second click on a given site is more likely

representative of true user intent than a ``doubleclick,'' we would

expect

to determine that a coupon is stale and should be

rejected. Since a second click on a given site is more likely

representative of true user intent than a ``doubleclick,'' we would

expect

![]() .

.

Of course, many different filtering policies are possible, as are many

different data structures and maintenance strategies for ![]() .

.

We implemented a prototype of our premium-click scheme. Four websites at separate IP addresses provide a simulated advertiser, publisher, attestor, and syndicator. The web sites are served by Apache 2.0.58, and server-side scripted with PHP 5.1.6. The database for click, ad, and coupon data is MySQL 5.0.26.

The cache cookie served by the attestor references an image hosted on

the syndicator. The URL used to request the image is created by

JavaScript when the cookie's HTML is rendered, and contains the secret

![]() (which is generated when the cache cookie is set) as well as

the referrer page, i.e., whichever page caused the cache cookie to

load. Later, when the cookie is loaded in conjunction with a click,

the URL of the referrer will reveal the ID of the publisher and the ID

of the advertisement that was clicked.

(which is generated when the cache cookie is set) as well as

the referrer page, i.e., whichever page caused the cache cookie to

load. Later, when the cookie is loaded in conjunction with a click,

the URL of the referrer will reveal the ID of the publisher and the ID

of the advertisement that was clicked.

The attestor needs to create and serve these cache cookies when the user logs in, so additional processing is required. However, creating a secret value takes very little time, and the cookie can be served in a hidden iframe. The result is no difference in experience for the user, and only a trivial amount of work for the attestor's servers.

In a production system, click analysis would be done after redirecting the client by adding it to a processing queue.

In deploying our premium-click scheme with multiple attestors,

![]() , it would be natural for a syndicator to share a unique key

, it would be natural for a syndicator to share a unique key ![]() with each attestor

with each attestor ![]() .

Given such independent attestor keys

.

Given such independent attestor keys ![]() , though, a coupon created by

, though, a coupon created by ![]() conveys and therefore reveals the fact that a user has visited the Web site of

conveys and therefore reveals the fact that a user has visited the Web site of ![]() . Observe, however, that in our scheme a publisher triggers the release of a coupon from the browser of a visiting user, but does not see the coupon. The syndicator receives the coupon, but does not directly interact with the user. In effect, the syndicator receives the coupon blindly.

While the syndicator does learn the IP address of the user, this is information that is typically already available: The only additional information that the syndicator learns is whether or not the user has received an attestation.

Thus, coupons naturally decouple information about the browsing patterns of users from the identities and browsing sessions of users. This is an important, privacy-preserving feature.

. Observe, however, that in our scheme a publisher triggers the release of a coupon from the browser of a visiting user, but does not see the coupon. The syndicator receives the coupon, but does not directly interact with the user. In effect, the syndicator receives the coupon blindly.

While the syndicator does learn the IP address of the user, this is information that is typically already available: The only additional information that the syndicator learns is whether or not the user has received an attestation.

Thus, coupons naturally decouple information about the browsing patterns of users from the identities and browsing sessions of users. This is an important, privacy-preserving feature.

Such decoupling occurs in the case when ads are outsourced, that is,

when the syndicator and publisher are separate. When the syndicator

and publisher are identical, i.e., when a search engine displays its

own advertisements, coupons may be linked to users, and therefore leak

potentially sensitive information. A couple of privacy-enhancing

measures are possible.

To limit the amount of leaked browsing implementation, our scheme may

employ a multiple-coupon technique discussed in depth in

Appendix A.

Alternatively, attestors may share a single key ![]() (or attestors may

have overlapping sets of keys). In this case, a MAC does not reveal

the identity of the attestor that created it. If a coupon

(or attestors may

have overlapping sets of keys). In this case, a MAC does not reveal

the identity of the attestor that created it. If a coupon

![]() is created, as we propose, with a random nonce

is created, as we propose, with a random nonce

![]() , then it conveys no information about a user's identity. In

principle, however, it would be possible for an attestor to embed a

user's identity in

, then it conveys no information about a user's identity. In

principle, however, it would be possible for an attestor to embed a

user's identity in ![]() , thereby transmitting it to the

syndicator. This transmission could even be covert: A ciphertext on a

user's identity, i.e., an encryption thereof, will have the appearance

of a random string. Proper auditing of the policy and operations of

the attestor or syndicator would presumably be sufficient in most

cases to ensure against collusive privacy infringements of this kind.

, thereby transmitting it to the

syndicator. This transmission could even be covert: A ciphertext on a

user's identity, i.e., an encryption thereof, will have the appearance

of a random string. Proper auditing of the policy and operations of

the attestor or syndicator would presumably be sufficient in most

cases to ensure against collusive privacy infringements of this kind.

As an alternative, ![]() might be based on distinctive, but verifiably

non-identifying values. For example,

might be based on distinctive, but verifiably

non-identifying values. For example, ![]() might include the IP

address5 and/or timestamp of the client to

which an attestor issues a coupon--perhaps supplemented by a small

counter value.6 A client could then verify that

might include the IP

address5 and/or timestamp of the client to

which an attestor issues a coupon--perhaps supplemented by a small

counter value.6 A client could then verify that ![]() was

properly formatted, and did not encode the user's identity. Of course,

was

properly formatted, and did not encode the user's identity. Of course,

![]() itself might then embed the user's identity. It is

possible, however, to eliminate the possibility of a covert channel in

the MAC by periodically refreshing

itself might then embed the user's identity. It is

possible, however, to eliminate the possibility of a covert channel in

the MAC by periodically refreshing ![]() and publicly revealing old values.

and publicly revealing old values.

Without possession of an attestor key, an adversary cannot feasibly forge new coupons, thanks to our use of MACs. An adversary could still bypass our scheme in several ways:

All of these attacks are possible in existing click-fraud schemes. The various techniques used to address them today are equally applicable to premium clicks. For example, a syndicator can direct its own client machines to a publisher's site to determine if the publisher is generating fraudulent clicks. Indeed, our premium-click scheme makes detection of misbehavior easier, as it permits a syndicator to ``mark'' a client coupon and therefore directly monitor the traffic generated by the client and even detect the emergence of stolen coupons.

An adversary can also try to exploit the special characteristics of our scheme as follows:

Since the syndicator is ultimately in control over deciding which clicks should be considered ``premium'' (and earns more when clicks are premium), publishers and advertisers may accuse the syndicator of improperly inflating the percentage of clicks considered premium. To solve this problem, an additional entity called an auditor can be contracted to watch the coupons that are released, and verify the premium-status judgement of the syndicator. The auditor would not be rewarded based on click traffic, so it would have no incentive to inflate or deflate the number of premium clicks from those that are legitimate.

The cache cookies set by attestors can be crafted so that, when an

advertisement's URL is clicked, the coupon

![]() is released both to the syndicator and to the auditor

who maintains an independent database. When the syndicator's numbers

are contested, the coupons recorded by the auditor can be used to

recompute the number of premium clicks for a given advertisement or

publisher, and compared to the syndicator's calculation.

is released both to the syndicator and to the auditor

who maintains an independent database. When the syndicator's numbers

are contested, the coupons recorded by the auditor can be used to

recompute the number of premium clicks for a given advertisement or

publisher, and compared to the syndicator's calculation.

In contrast to today's heuristic filtering methods for eliminating ``bad'' clicks, our premium-click scheme relies on a foundation of cryptographic authentication to validate ``good'' clicks. Premium clicks are by no means a cure-all for fraud, and are themselves subject to attack. The value of premium clicks lies in the way that they provide new, cryptographically authenticated visibility into click traffic, and thus a new, stronger platform for combating click fraud.

While premium clicks could in principle supplant current filtering schemes entirely, they are attractive in that they can be deployed in a complementary fashion alongside existing systems. We have proposed a new advertising model in which advertisers pay a higher charge for premium clicks. We believe that such a scheme might be launched experimentally by a syndicator with minimal impact on existing business and then expanded as its success warrants. Thus premium clicks promise offer not only a new approach to click fraud, but one with a practical path to fruition.

User privacy in our premium-click scheme depends upon how the value ![]() is formed, and on the number and content of the coupons cached in a user's browser. Let us now therefore consider a system with multiple attestors,

is formed, and on the number and content of the coupons cached in a user's browser. Let us now therefore consider a system with multiple attestors,

![]() . Each attestor

. Each attestor ![]() shares a key

shares a key ![]() with the syndicator. We now describe the technical challenges that arise with multiple attestors.

with the syndicator. We now describe the technical challenges that arise with multiple attestors.

The simplest way to circumvent these difficulties in our premium-clicks scheme is to manage only a single slot, that is, to maintain only a single cache cookie in a given user's browser. Only the cache cookie planted most recently by an attestor will then persist. Provided that the syndicator regards all attestors as having equal authority in validating users, this approach does not result in any service degradation.

If, however, the syndicator desires the ability to harvest multiple coupons, then attestors must use multiple slots. One possible approach is to maintain an individual slot for each attestor, i.e., to let ![]() . If the number of attestors is small, this may be workable. Alternatively, attestors may plant coupons in random slots, sometimes supplanting previous coupons, or subsets of attestors may share slots. The syndicator might, for example, assign different weight to attestors, according to the anticipated reliability of their attestations; attestors with the same rating might share a slot.

. If the number of attestors is small, this may be workable. Alternatively, attestors may plant coupons in random slots, sometimes supplanting previous coupons, or subsets of attestors may share slots. The syndicator might, for example, assign different weight to attestors, according to the anticipated reliability of their attestations; attestors with the same rating might share a slot.

It is preferable, therefore to create attestor keys ![]() in an independent manner. In this case, a coupon

in an independent manner. In this case, a coupon

![]() is cryptographically bound to the attestor that created it. That is, only attestor

is cryptographically bound to the attestor that created it. That is, only attestor ![]() , with its knowledge of

, with its knowledge of ![]() , can feasibly create

, can feasibly create ![]() of this form. To enable the syndicator to determine the correct key for verification of the MAC, the coupon must be supplemented with

of this form. To enable the syndicator to determine the correct key for verification of the MAC, the coupon must be supplemented with ![]() , the identity of the authenticator. For example, we might let

, the identity of the authenticator. For example, we might let

![]() , where

, where ![]() is a random nonce.

is a random nonce.