Nate Kushman

Srikanth Kandula

Dina Katabi

Bruce M. Maggs

nkushman@mit.edu

kandula@mit.edu

dk@mit.edu

bmm@cs.cmu.edu

Our objective is to ensure that Internet domains stay connected as long as the underlying network is connected. Our solution, R-BGP works by pre-computing a few strategically chosen failover paths. R-BGP provably guarantees that a domain will not become disconnected from any destination as long as it will have a policy-compliant path to that destination after convergence. Surprisingly, this can be done using a few simple and practical modifications to BGP, and, like BGP, requires announcing only one path per neighbor. Simulations on the AS-level graph of the current Internet show that R-BGP reduces the number of domains that see transient disconnectivity resulting from a link failure from 22% for edge links and 14% for core links down to zero in both cases.

BGP often loses connectivity even when the underlying network continuously has a path between the sender and the receiver. Indeed, in the above studies, the underlying network continuously has such a path. The Internet topology is known for its high redundancy, even when considering only policy compliant interdomain paths [13,36]. Hence, transient disconnectivity due to protocol dynamics is unwarranted. The objective of this work is to ensure that Internet domains are continuously connected as long as policy compliant paths exist in the underlying network.

Past work in this area has focused purely on shrinking convergence times [9,18,29,34]. Such approaches, however, are intrinsically limited by the size of the Internet and the complexity of the BGP protocol.

We take a fundamentally different approach. We focus on protecting data forwarding. Instead of trying to reduce the period of convergence, we isolate the data plane from any harmful effects that convergence might cause. Specifically, while waiting for BGP to converge to the preferred route, we set the data plane to forward packets on pre-computed failover paths. Thus, packet forwarding can continue unaffected throughout convergence.

Our failover design addresses two important challenges: (a) Ensuring Low Overhead: The size and connectivity of the Internet make a naive advertisement of alternate failover paths unscalable. Announcing multiple paths to each neighbor could lead to explosion of the routing state, and announcing even a single failover path per neighbor could lead to excessive update traffic. Instead, in our design, a domain announces only one failover path to one strategic neighbor.

(b) Guaranteeing Continuous Connectivity: The real difficulty in using failover paths lies in ensuring connectivity while progressing from the failover state to the final converged state. Inconsistent state across Internet domains can cause forwarding loops, or lead domains to believe that no path to the destination exists even when such a path does exist. We address the consistency problem by annotating BGP updates with a small amount of information that prevents transient routing loops and ensures that forwarding is never updated based on inconsistent state.

Our solution, R-BGP (Resilient BGP), needs only a few simple and practical changes to current BGP. It pre-computes a few strategically chosen failover paths and maintains enough state consistency across domains to ensure continuous path availability. R-BGP has these properties:

We evaluate R-BGP using simulations over the actual Internet AS topology. Our empirical results show that, when a link fails, R-BGP reduces the number of domains temporarily disconnected by the dynamics of interdomain BGP from 22% for edge links and 14% for core links down to zero in both cases. Even in the worst case when multiple link failures affect both the primary and the corresponding failover path, R-BGP avoids 80% of the disconnectivity seen with BGP. Furthermore, R-BGP achieves this performance with message overhead comparable to BGP and reduced convergence times.

Ensuring that routing protocols recover from link failures with minimal losses is an important research problem with direct impact on application performance. Significant advances have been made in supporting sub-second recovery and guaranteed failover for intradomain routing in both IP and MPLS networks [11,28,32,33], but none of these solutions apply to the interdomain problem. The main contribution of this paper is to provide immediate recovery guarantees for interdomain routing, using scalable, practical and provably correct mechanisms.

BGP is a policy-based protocol. Rather than simply selecting the route with the shortest AS-path, routers use policies based on commercial incentives to select a route and to decide whether to propagate the selected route to their neighbors. The policies are usually guided by AS relationships, which are of two dominant types: customer-provider and peering [13]. In the former case, a customer pays its provider to connect to the Internet. In peering relationships, two ASes agree to exchange traffic on behalf of their respective customers free of charge. Most ASes follow two polices for routing traffic: ``prefer customer'' and ``valley-free''. Under the ``prefer customer'' routing policy, an AS always prefers routes received from its customers to those received from its peers or providers. Under the ``valley-free'' routing policy, customers do not transit traffic from one provider to another, and peers do not transit traffic from one peer to another.

Finally, BGP comes in two flavors: routers in different ASes exchange routes over an eBGP session, whereas routers within the same AS use iBGP.

Prior work on failover paths is mainly within the context of intradomain routing. For example, in MPLS networks, it is common to use MPLS fast re-route which routes around failed links using pre-computed MPLS tunnels [28]. In IP networks, there are a few proposals for achieving sub-second recovery when links within an AS fail [11,23,33], this work does not extend to the interdomain context because it assumes a monotonic routing metric, ignores AS policies, and requires strict timing constraints.

Lastly, prior work on failover paths in the interdomain context does not provide a general solution for continuous connectivity. The authors of [8] have proposed a technique for immediate BGP-recovery for dual-homed stub domains. Their solution, however, does not generalize to other types of domains, and requires out-of-band setup of many interdomain tunnels. Also, the authors of [36] propose a mechanism that allows neighboring ASes to negotiate multiple BGP routes, but in contrast to our work they do not use these routes to protect against transient disconnectivity or provide connectivity guarantees.

(a) Fast enough convergence is unlikely: Given the size of the Internet, it is difficult, if not impossible, to design an interdomain routing protocol that converges fast enough for real-time applications. The convergence time of BGP is limited both by the time it takes routers to process messages, and by rate-limiting timers instituted to reduce the number of update messages. There's an inherent trade-off between these two however: set the timers too low and convergence is limited by the time it takes routers to process the additional updates; set the timers too high and convergence is limited by the time it takes for the timers to expire. Currently, routers use a timer called the Minimum Route Advertise Interval (MRAI) to limit the time between back-to-back messages to the same neighbor for the same destination to 30 seconds, by default. Griffin et. al. [14] show that we cannot expect a net gain in convergence time by reducing this default, yet real-time applications such as VoIP and games cannot handle more than a couple seconds of disconnectivity, thus even a single MRAI of outage can be devastating for them [17].

(b) Focus on convergence limits innovation: Imposing strict timing constraints on convergence stifles innovations in interdomain routing. For example, it is desirable for interdomain routing to react to performance metrics by moving away from routes with bad performance [36]. However, such an adaptive protocol will likely spend longer time converging because it explores a larger space of paths and changes paths more often. A mechanism to protect the data-plane from loss during convergence will be a key component of any research into richer routing and traffic engineering options.

The rest of this paper details the problem and presents R-BGP (Resilient BGP), a few simple and practical modifications to BGP that ensure continuous AS-connectivity. We present R-BGP in the context of a single destination; this keeps the description simple but also complete, since BGP is a per-destination routing protocol. Further, we first describe the problem and solution at the AS level, referring to each AS as one entity and ignoring router-level details. Then in §7, we discuss router-level implementations.

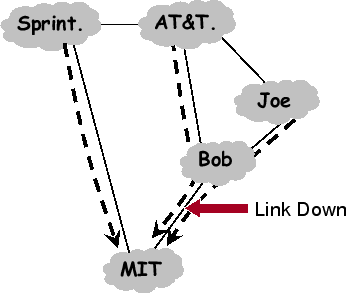

Consider the example in Fig. 1, where MIT buys service from both Sprint and a local provider Bob, who in turn buys service from AT&T and Joe. Traffic sent to MIT flows along the dashed arrows in the figure.

In BGP, an AS advertises only the path that the AS uses to reach the destination. Since all of Bob's neighbors are using his network to route to MIT, none of them announces a path to Bob, and Bob knows no alternate path to MIT. Thus, if the link between Bob and MIT fails, Bob can no longer forward packets to MIT and has to drop all packets, including those from AT&T and Joe. Eventually, Bob will withdraw his route to MIT, resulting in AT&T advertising the alternate path through Sprint. Now that Bob knows again a path to MIT, it resumes packet forwarding.

This is an example of a transient disconnectivity. Specifically, Bob has suffered temporary disconnectivity to MIT even when the underlying AS-graph contains an alternate path. Note that the harm of transient disconnectivity is not limited to the AS without a path. In this example, AT&T also suffers transient disconnectivity to MIT even though it knows of an alternate path.

In practice, transient disconnectivity is typical whenever routes

change, and might last for a few minutes [22,35]. This

delay stems from several causes. First, a usable path might not be

available at the immediate upstream AS forcing the withdrawal to

percolate through many ASes until reaching an AS that knows an

alternate path. Further, searching for a usable path involves

discarding many alternatives. For example, AT&T might first switch

to the customer route ``Joe

![]() Bob

Bob

![]() MIT'' but

will have to discard it when Joe reacts to Bob's withdrawal by

withdrawing his route. Finally, this delay is exacerbated because a

link failure creates a flurry of update messages for all destination

prefixes that were using the link, thus delaying processing at nearby

routers [7].

MIT'' but

will have to discard it when Joe reacts to Bob's withdrawal by

withdrawing his route. Finally, this delay is exacerbated because a

link failure creates a flurry of update messages for all destination

prefixes that were using the link, thus delaying processing at nearby

routers [7].

|

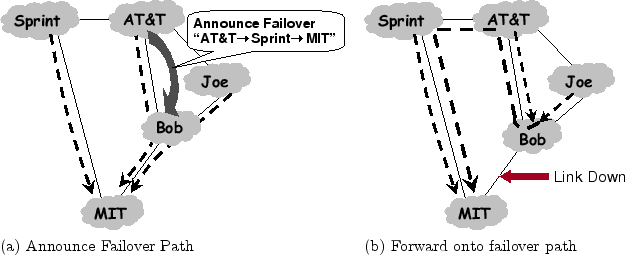

To achieve our goal, we use failover paths. Failover as an idea to solve the transient disconnectivity problem is conceptually simple; instead of searching for a new path to the destination after a link fails, as is the case in current BGP, pre-compute an alternate path before the link fails.

For example, in Fig. 1, with current BGP, Bob drops

MIT's packets when its link to MIT fails. During BGP convergence,

Bob learns of Sprint's path to MIT, uses it, and stops dropping

packets. In contrast, in a failover solution, AT&T advertises to

Bob the path ``AT&T

![]() Sprint

Sprint

![]() MIT'', labeled

as a failover path, as shown in Fig. 2a. As long as

Bob's link to MIT is operational, the failover path is not used, and

traffic follows standard BGP; but, if the link between Bob and MIT

fails, Bob immediately diverts MIT's traffic to the failover path,

i.e., he diverts the traffic to AT&T, who will forward it along the

failover path to Sprint. As shown in Fig. 2b, the

failover path saves Bob, Joe and AT&T from experiencing

transient disconnectivity to MIT.

MIT'', labeled

as a failover path, as shown in Fig. 2a. As long as

Bob's link to MIT is operational, the failover path is not used, and

traffic follows standard BGP; but, if the link between Bob and MIT

fails, Bob immediately diverts MIT's traffic to the failover path,

i.e., he diverts the traffic to AT&T, who will forward it along the

failover path to Sprint. As shown in Fig. 2b, the

failover path saves Bob, Joe and AT&T from experiencing

transient disconnectivity to MIT.

The conceptual simplicity of the failover idea hides three significant challenges.

|

Advertising failover paths adds little update message overhead because each domain advertises at most one path to each neighbor, just like current BGP. To see this, recognize that an AS should not advertise its best path to the neighbor currently used to reach that destination, since this path would be a loopy (unusable) path to this neighbor. BGP's poison-reverse policy ensures that a withdrawal be sent in this case. R-BGP replaces this poison-reverse withdrawal with an advertisement of the failover path, keeping the overhead at a minimum.

The above rule also simplifies the implementation of failover paths in a way that is secure and has little forwarding overhead. If an AS were to announce multiple paths to a neighbor, it will need an additional signaling mechanism, such as marking the packets, to identify which path to use to forward packets coming from that neighbor. Such signaling mechanisms can be expensive, as the IP header has no free bits, and may require additional security mechanisms. Since R-BGP offers the failover path only to the neighbor used to reach the destination, only packets from this neighbor are forwarded on the failover path. This requires no additional signaling, and no additional security mechanisms to prevent abuse. Finally, though the failover path advertisement rule may appear too restrictive, we will prove that it is enough to achieve continuous connectivity.

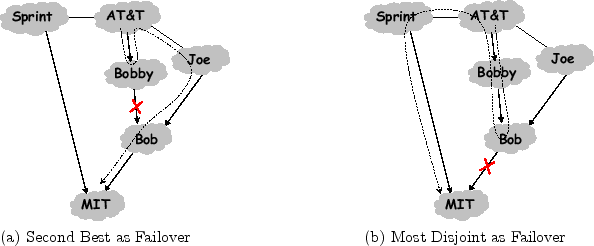

At first, it might seem that an AS should advertise the second-best route as a failover path, but it is likely that there is significant overlap between the primary and the second-best path, causing both paths to be unavailable at the same time. Consider the modified scenario in Fig. 3, where we inserted a new ISP, Bobby, between AT&T and Bob. Solid arrows represent primary paths to MIT and dotted lines represent failover paths. In this new scenario, AT&T's primary path goes through Bobby then Bob. Its second-best path is via Joe because ASes usually apply a ``prefer customer'' policy, and Joe is AT&T's customer whereas Sprint is AT&T's peer. Assume AT&T advertises its second-best path to Bobby, its next-hop AS on the primary, as a failover path. This failover path is useful if the link between Bobby and Bob fails, in which case Fig. 3a shows the path taken by the packets after the failure. The second-best path does not help, however, if the link between Bob and MIT fails. If AT&T had advertised the path via Sprint instead, it would have been possible to protect against either of the two failures. This leads us to the simple intuition - the more disjoint the failover path is from the primary, the more link failures it can protect against. Thus, our strategy for failover paths is:

MECHANISM 1 - FAILOVER PATHS: Advertise to the next-hop neighbor a failover path that, among the available paths, is the one most disjoint from the primary.

We note a few important subtleties. First, a domain must check all paths it knows, including failover paths, to pick the one most disjoint from its primary. For example, in Fig. 3b, Bobby's most disjoint path is the failover path he learned from AT&T, and hence he advertises this path to Bob. Note that it may not be policy compliant to advertise this path to the next-hop neighbor. The failover path, however, will only be used for a short period during convergence, and it is used to guarantee connectivity to the advertising AS. Thus, we believe most ASes are willing to advertise such paths. Regardless, we show experimentally, that even using only policy compliant paths still eliminates most transient disconnectivity.

Second, note that the disjointness of two paths is defined in term of their shared suffix. In particular, any destination based routing protocol, including BGP, creates a routing tree to reach the destination. Once two paths going to the destination meet at an AS, they do not diverge again because no AS will announce multiple routes to the same destination. This means that at convergence two paths to the destination can only have a common suffix. The smaller the length of this common suffix, the less likely the two paths will fail simultaneously. Lastly, if multiple paths are equally disjoint from the primary path, then the normal BGP algorithm is used to choose between them.

|

Let us go back again to the Bob-AT&T example introduced in Fig. 2 at the beginning of this section. When the link between Bob and MIT fails, Bob knows a failover path through AT&T. But Joe does not know any failover path; neither AT&T nor Bob sends through Joe, and thus none of them offers Joe a failover path.

We claim that it is not necessary for every AS to know a failover path for every link that can fail in order to achieve our goal. In fact, it suffices if each AS is responsible only for the links immediately downstream of it. The intuition for this is simple: if the AS immediately upstream of a failed link knows a failover path, packets of all upstream ASes are automatically protected. In the above example, as long as Bob knows a failover path for when the link Bob-MIT goes down, Joe's packets will see no loss. Further, in this example Joe is responsible for knowing a failover path only if the link between Joe and Bob fails, and AT&T is responsible for knowing a failover path only if the link between AT&T and Bob fails.

Thus, in order to achieve the first step in ensuring continuous connectivity, we need only show that Mechanism 1 ensures the AS immediately upstream of the down link always has a failover path on which to send packets. We show this by proving:

Lemma A.4 If any AS using a down link will have a path to the destination after convergence, then R-BGP guarantees that an AS which is using the down link and adjacent to it knows a failover path when the link fails.

The formal proof is in the appendix, but the intuition is simple. Let Bob be the AS immediately upstream of the failing link. One of two cases will apply.

To see how a routing loop can be formed during convergence, we

re-visit the previous example. In Fig. 4a, the link

Bob

![]() MIT is down and Bob has switched over to the

failover path through AT&T. Now, Bob has no path to announce to

AT&T or even to Joe because with normal BGP policies the path through

one provider (AT&T here) is not advertised to another provider. Hence,

Bob withdraws his route to MIT as in Fig. 4a.

Unfortunately, these BGP updates do not indicate the reason for the

withdrawal; so both AT&T and Joe believe that the other might

be still be able to route through Bob, and thus together they

mistakenly create a routing loop. In short, AT&T attempts to route

along ``Joe

MIT is down and Bob has switched over to the

failover path through AT&T. Now, Bob has no path to announce to

AT&T or even to Joe because with normal BGP policies the path through

one provider (AT&T here) is not advertised to another provider. Hence,

Bob withdraws his route to MIT as in Fig. 4a.

Unfortunately, these BGP updates do not indicate the reason for the

withdrawal; so both AT&T and Joe believe that the other might

be still be able to route through Bob, and thus together they

mistakenly create a routing loop. In short, AT&T attempts to route

along ``Joe

![]() Bob

Bob

![]() MIT'' while Joe attempts to route along ``AT&T

MIT'' while Joe attempts to route along ``AT&T

![]() Bob

Bob

![]() MIT''

causing the loop. Eventually, normal BGP will fix the loop but

packets to MIT will be stuck in the loop and suffer drops until then.

MIT''

causing the loop. Eventually, normal BGP will fix the loop but

packets to MIT will be stuck in the loop and suffer drops until then.

We observe that the routing loop could be avoided if AT&T and Joe could determine that Bob's withdrawal renders the old paths through each other unavailable. This is possible if Bob includes in its update to Joe and AT&T Root Cause Information (RCI) indicating that the link between Bob and MIT is no longer available, preventing Joe and AT&T from attempting to route on any paths that use this link. This leads to our second mechanism:

MECHANISM 2 - ROOT CAUSE INFORMATION: Include in each update message Root Cause Information indicating which other paths will not be available as a result of the same root cause event.

We defer the details of implementing RCI until §7.3. The idea of including in each update its root cause, however, is not new. Prior work [24,30] uses root cause information to reduce BGP convergence time and number of messages. R-BGP benefits from the reduced convergence time and reduced number of messages provided by RCI, but is novel in using RCI to prevent routing loops during convergence. Assuming the valley-free and prefer-customer policies, we prove that using RCI eliminates transient routing loops:

Lemma A.9

Consider a network that is in a converged state at time ![]() , when

a link fails, and converges again at

, when

a link fails, and converges again at ![]() . At no time between

. At no time between ![]() and

and ![]() do the forwarding tables contain any loops.

do the forwarding tables contain any loops.

The intuition underlying the proof is that loops occur because at least one AS tries to use an out-of-date route. RCI allows an AS to locally purge out-of-date routes, preventing the creation of transient loops. The details of the proof are in the Appendix.

MECHANISM 3A - USE OLD PRIMARY PATHS: When left without a usable primary path, the AS immediately upstream of a down link forwards along the failover path, and all other ASes continue to forward along their old primary path.

Thus, even though the path through Bob has been withdrawn, Joe can temporarily use the withdrawn path to forward packets to the destination.

Using old paths in this way, however, raises another question: How long can Joe use this old primary path? Ideally, Joe would use the old primary path until one of his neighbors announces a new path or he knows that he will not have a path after convergence. The first part is simple; If a neighbor announces a path, Joe just moves to the new path because, as we have just proven, RCI guarantees that this new path will be loop-free and will not traverse the down link.

The second part has a catch though- in current BGP an AS cannot tell whether a neighbor will eventually announce a path to him. This decision must be handled carefully, not waiting long enough may cause premature packet-loss, but waiting too long can create a deadlock state leaving an AS indefinitely forwarding along an old path. To precisely determine whether an AS will have a path after convergence requires an individual AS to ascertain a global property of the network using only the local information available to it. Griffin et al. have proven that even with access to the entire link state of the Internet, and all policies of all ASes, it is an NP-complete problem just to determine if the network will converge, without even attempting to determine the state to which it will converge [15].

The Internet has an inherent structure to it, however, and we take advantage of this structure to allow an AS to determine when it will know an available path. In particular, most paths on the Internet are valley-free [12], that is all ASes on the path pursue economic interests by offering the path only if it goes to or from a customer. Focusing on this common case of valley-free paths, allows R-BGP to provide the global guarantee of continuous connectivity, while using only local information available to each AS. We use the following Mechanism to communicate the required information to allow an AS to locally determine the global property of whether it will eventually have an available path:

MECHANISM 3B - ENSURING CONVERGENCE: An AS stops forwarding internally originated traffic along withdrawn primary paths or failover paths when explicit withdrawals have been received from all neighbors. An AS delays sending a withdrawal to a neighbor until it is sure it will not offer this neighbor a valley-free path at convergence.

To see how this works, suppose another neighbor John is using Joe to get to MIT as shown in Fig. 5b. After Bob withdraws his route from Joe, Joe knows no route to MIT, until AT&T announces a new path. Joe waits until AT&T withdraws its current path, which contains the down link, or replaces it by a new path before sending a withdrawal to John, thus ensuring continuous connectivity for John. In contrast, it sends a withdrawal to AT&T as soon as it hears the withdrawal from Bob, since it knows it will not have a valley-free path to offer AT&T at convergence. This prevents a deadlock where Joe and AT&T are waiting on each other to send withdrawals.

More generally, an AS knows it will not offer a valley-free path to a non-customer once it has heard withdrawals or advertisements of non-valley free paths from all customers. Additionally, it knows it will not offer a valley-free path to a customer once it has heard withdrawals or non-valley-free advertisements from all neighbors. To identify paths which are valley-free, advertisements include an additional bit indicating whether or not a path is valley-free.

Since valley-free paths are also loop-free, enforcing that delayed withdrawals only follow valley-free paths allows R-BGP to ensure continuous connectivity in the common case when ASes are following valley-free and prefer-customer policies, and still avoid deadlock regardless of policies. Formally, Mechanism 3b ensures:

Theorem A.10 Regardless of policies, in a converged state, no AS is deadlocked waiting to send an update, and no AS is forwarding packets along a withdrawn or failover path.

Lastly, note that to ensure continuous connectivity, ASes continue to forward traffic received from their neighbors.

Theorem A.11

Consider a network which is in a converged state at time ![]() , when a

link goes down, and converges again at

, when a

link goes down, and converges again at ![]() . Assuming the

valley-free, and prefer-customer policies, if an AS

. Assuming the

valley-free, and prefer-customer policies, if an AS ![]() knows a path

to destination

knows a path

to destination ![]() at times

at times ![]() and

and ![]() , then at any time between

, then at any time between

![]() and

and ![]() the forwarding tables contain a path from

the forwarding tables contain a path from ![]() to

to ![]() .

.

The proof of this theorem is in the Appendix. This last theorem is the culmination of R-BGP design. It proves that R-BGP achieves the goal stated at the beginning of this section. Specifically, R-BGP ensures that any two domains stay connected as long as the underlying AS-graph has a valley-free policy compliant path that goes between them.

We can optimize the forwarding memory overhead by combining the primary and failover tables entries into a single integrated forwarding table. Most high speed router architectures have a level of indirection between the destination IP look-up, and the forwarding entries which contain the next-hop information used to forward the packet. The memory in the forwarding table is typically dominated by the IP look-up portion, because this is usually stored as a tree in a relatively memory inefficient way in order to facilitate fast look-ups. Note that R-BGP does not increase the number of entries (prefixes) in the forwarding table, rather it stores two pieces of information for each prefix - the primary and the failover next hop information. Hence, both primary and failover forwarding entries can be merged into a single table, eliminating the overhead of storing a second tree. The look-up tree need only be extended to store at each leaf two indices into the table storing next-hop information, one for the primary next-hop information, and one for the failover next-hop information.

Furthermore, it is possible to completely eliminate any need for additional memory on the line cards of the router. To do so, one stores the failover table on a specialized dummy line card in the router with no physical interfaces of its own. All packets arriving on any failover virtual interface on the router would be sent to this dummy line card, which would perform the look-up in its copy of the failover table, and ensure the packet is forwarded accordingly. One line card per router should provide sufficient capacity as long as multiple links connected to a given AS do not fail at the same time. This is similar to line cards built to handle tunnel encapsulation and decapsulation at line speed [2,4].

When a router in (s1) receives a packet, it will receive the packet along a primary virtual interface. Since the primary virtual interface is associated with the primary forwarding table, the packet arrival will trigger a look-up in this forwarding table. For routers in (s1), the result of such a look-up will be the primary virtual interface towards the next-hop router on the primary path.

This continues until the packet reaches (s2), i.e., until it reaches the router immediately upstream of the down link. Since packets arrive at this router along a primary virtual interface they again trigger a look-up in the primary forwarding table. This router uses Bidirectional Forwarding Detection [19] to quickly detect the link failure and it populates all entries in its primary forwarding table that use the down link with the associated failover path entries instead. Thus, on this router, a look-up in the primary forwarding table will result in a failover virtual interface.

Thus, the packet will continue to be forwarded along failover virtual interfaces, with all look-ups performed on failover forwarding tables, until it reaches (s3), i.e., until it reaches a router that knows a primary path that does not contain the down link. This router will have an entry in its failover forwarding table that contains a primary virtual interface. From this point on to the destination, the packet will be forwarded along primary virtual interfaces, with look-ups performed only in primary forwarding tables.

Root Cause Information (RCI) is created and forwarded whenever a link changes state. Note that when a link changes state, at most one of the the two routers adjacent to the link, i.e., whichever router uses the link for the given destination, will generate an update to its primary path. This root cause router attaches its AS number, a router identifier and the new link state to all updates generated as a result of the link state change. This information is called Root Cause Information (RCI). Routers that change their routes as a result of receiving such an update message, copy the RCI in the received update into the update messages they generate. This allows any router whose paths are affected by this link state change to learn the unique root cause that triggered the series of update messages and purge other routes that include the down link from its routing table.

Encoding the appropriate link state change information is non-trivial, however, since updates triggered by different root cause events may propagate at different speeds. For example, if a link flaps (i.e., a link goes down and then immediately comes back up), the link down update may arrive at a router after an update from another neighbor announcing the link up event, causing the router to mistakenly assume the link is still down.

To solve this problem, R-BGP uses a monotonically increasing sequence number per BGP router and includes in the RCI both the identifier and the sequence number of the root-cause router. Further, in a router's BGP RIB, the AS-Path information includes for each AS in the AS-PATH, the egress router for that AS, and that router's sequence number. Upon receiving an update with RCI, the router purges a route if any of the route's AS-PATH entries matches both the AS and the router identifier in the update's RCI, and has a lower associated sequence number than the update's RCI. When an interdomain link goes down, all ASes on the affected AS-paths will receive updates with the root-cause router's RCI and will mark these paths as withdrawn. This is sufficient to prevent interdomain loops (Lemma A.9).

The algorithms used to produce the policies have some limitations. First, the algorithms sometimes produce provider-customer loops. It is well known that such loops do not exist in the Internet, and could lead to persistent BGP loops [12]. Thus, we eliminate them by finding the AS in the loop with the fewest neighbors, and removing the edge between this AS and the next AS in the loop (its customer). Second, when one ISP spans multiple AS numbers, the algorithm in [10] assign these ASes a sibling relationship. We treat sibling relationships as peer-peer, since treating them as anything else also leads to provider-customer loops.

(1) Dual-Homed Edge Domains: It is common in today's Internet for edge domains to be multi-homed. Multi-homing is sought after to improve resilience to access link failure. But how effective is such a backup approach in preventing transient disconnectivity? To answer this we look at the effect of taking down a link connected to a dual homed edge domain. For each of the 9200 dual-homed edge domains in our AS graph, we run a simulation, in which we take down one of the domain's two access links, and ask how many source ASes will experience transient disconnectivity to the domain. Specifically, we compare the performance of BGP and the R-BGP variants using the following metric: Among the sources that will be connected to the dual homed edge domain after BGP converges, what fraction will see disconnectivity during convergence? We also use this scenario to determine the performance of the various protocols when multiple links are taken down, and when a link comes back up at the same time that another goes down. Further, we quantify the relative overhead of the various versions of R-BGP by measuring the number of routing messages exchanged and the time to converge.

(2) Core Link Down: While the above scenario looks at access links, many more ASes can be affected when core links fail and so it's important to confirm that R-BGP avoids transient disconnectivity in these scenarios as well. We define a core link as a connection between two non-stub domains. In this scenario we compare the various protocols on the following metric: Among the AS pairs that were using the down core link, and will be connected after BGP converges, what fraction will see disconnectivity during convergence? For each of the 200 links that we tested, we ran 24142 simulations, one for each possible destination AS, and averaged the results across links.

![\includegraphics[width=4in, clip]{figures/barGraph-onedown.eps}](img11.png)

|

The figure also shows that all variants of R-BGP significantly increase resilience to transient disconnectivity. R-BGP performs adequately when working within the confines of current policies; using policy compliant most disjoint paths for failover allows disconnectivity in only 1.4% of the cases. This means that even if ASes are not willing to temporarily provide transit for their non-customers, R-BGP still avoids almost all disconnectivity. Announcing the second best path as a failover path, though does not perform as well, allowing 5.2% of the domains to be temporarily disconnected. This is because often there is much overlap in the best and the second-best paths, reducing the number of link failures that the failover paths cover. Still, even an R-BGP variant that uses the second best path for failover is significantly better than current BGP.

Again, considering the dual-homed edge domain scenario, Fig. 7 plots the cumulative distribution of the number of updates exchanged across each link in the graph, when routes converge after one of the two links of a dual-homed destination is brought down. The figure shows that 92% of interdomain links see at most one update during convergence for all protocols. R-BGP with most disjoint failover paths sends fewer messages than the other variants. Further, all variants of R-BGP send a number of messages comparable to BGP.

![\includegraphics[width=7in, clip]{figures/numupdates-camera.eps}](img12.png)

|

It might look surprising that R-BGP sometimes sends fewer updates than current BGP. This is due to the Root Cause Information (RCI) mechanism described in §6.2. In particular, when a link fails, current BGP may move to an alternate route that contains the same failed link and advertise this new route to neighboring ASes. RCI provides an AS with enough information to locally purge all routes that traverse the failed link, thus preventing such useless updates and significantly reducing path exploration. One may wonder whether RCI significantly decreases the number of messages and the failover advertisements eat most of this decrease, making the overall number of messages on par with BGP. This however is not the case. The number of messages with just RCI is only a bit smaller, but we omit these results here to enhance readability.

Fig 8 plots the cumulative distribution of the convergence time for each protocol when one link of a dual-homed domain is brought down. It shows that, on average, R-BGP tends to converge faster than BGP. Again this is because RCI eliminates unproductive path exploration during convergence. In our simulations, all R-BGP variants never took longer than 106s to converge, whereas BGP needed as long as 323s in certain cases. Again, RCI alone only does slightly better than R-BGP-it always converges within 96s, indicating that the overhead of the failover paths adds little to the convergence time.

![\includegraphics[width=7in, clip]{figures/updatetimes-camera.eps}](img13.png)

|

Fig. 9 shows that R-BGP reduces the number of disconnected sources from 32.9% to 6.8%, avoiding 80% of the disconnectivity seen with BGP. The intuition is that even though the failover path of the first failed link is broken, the failover path of the second failed link may still be operational, thus avoiding disconnectivity.

![\includegraphics[width=4in, clip]{figures/barGraph-twodown.eps}](img15.png) |

Specifically, we simulate the following worst case scenario for R-BGP. We pick one of the two access links of a dual-homed AS and bring down its preferred failover path by bringing down a link on that path. This triggers a change in the failover path. After the network has converged, we fail the access link of the dual-homed AS. At the same time, we bring up the previously failed link of most preferred failover path. This triggers a change in the failover path while it is in use.

Fig. 10 shows that despite ongoing convergence on the failover path, no packets are dropped when the primary path goes down. In contrast, BGP causes over 35% of the ASes to lose connectivity to the dual-homed AS. Surprisingly, this number is significantly larger than the percentage of AS disconnectivity caused by BGP when a single link goes down. The fact that two events occurred together increases BGP transient disconnectivity despite that one of the events is a link up. This surprising fact is consistent with prior results that show that BGP might experience disconnectivity even when a single link comes up [35].

![\includegraphics[width=4in, clip]{figures/barGraph-oneuponedown.eps}](img16.png) |

![\includegraphics[width=4in, clip]{figures/barGraph-random.eps}](img17.png) |

Additionally, note that R-BGP using most disjoint policy compliant paths sees the largest relative improvement, as we look at core link failures instead of edge link failures. To see why this is the case, note that if an AS remains disconnected after convergence, it cannot know a policy compliant failover path before the link fails but, if most disjoint paths, regardless of policy, are used the AS is guaranteed to have a failover path (Lemma A.4). Such persistently disconnected ASes and any AS that uses a path through such an AS will see transient disconnectivity when R-BGP restricts to most disjoint policy compliant failover paths. In our experiments, we see that persistently disconnected ASes tend to be long haul backbones like Abilene and GEANT that are primarily connected to stub ASes and don't have providers of their own. Such specialized long haul backbones are used more commonly by access networks that do not have a long haul backbone of their own in order to connect between regional offices. Since paths through a core link are less likely to involve this type of long haul backbone AS, a correspondingly smaller fraction of paths using a core link are affected by whether the most disjoint path is restricted to be policy compliant.

We model the network as a directed graph in which each node represents

a single-router autonomous system (AS). We analyze the scenario in

which BGP is in a converged state at time ![]() , then a link

, then a link ![]() goes

down, and finally BGP converges again at time

goes

down, and finally BGP converges again at time ![]() . We assume

that between times

. We assume

that between times ![]() and

and ![]() no other events occur, i.e., no

other links come up or go down. We also assume that during this time

no customer-provider-peer relationships between ASes change, and that

no AS changes its policy regarding which routes are preferred and to

whom those routes are advertised. Without loss of generality, we

analyze the available paths to one prefix

no other events occur, i.e., no

other links come up or go down. We also assume that during this time

no customer-provider-peer relationships between ASes change, and that

no AS changes its policy regarding which routes are preferred and to

whom those routes are advertised. Without loss of generality, we

analyze the available paths to one prefix ![]() during the transition.

We use

during the transition.

We use ![]() to denote the AS ``upstream'' of the failing link

to denote the AS ``upstream'' of the failing link ![]() ,

i.e., the AS which is forwarding packets for

,

i.e., the AS which is forwarding packets for ![]() along link

along link ![]() .

.

At various points in the analysis we make assumptions about routing policy. In order to state these assumptions, we must introduce several definitions. First, we assume that every edge in the network has a label indicating the relationship between its endpoints, either customer-to-provider, provider-to-customer, or peer-to-peer. Oppositely directed edges have reversed labels. We also assume that there are no cycles consisting entirely of customer-to-provider edges or provider-to-customer edges.

We say that a (directed) path in the network is valley free if a

link labeled either provider-to-customer or peer-to-peer can only be

followed by a link labeled provider-to-customer.

We say that an AS ![]() observes a valley-free policy if it never

advertises a path from a non-customer to a non-customer.

observes a valley-free policy if it never

advertises a path from a non-customer to a non-customer.

We say that an AS ![]() observes a prefer-customer policy, if

observes a prefer-customer policy, if ![]() always prefers a path that is advertised by a customer of

always prefers a path that is advertised by a customer of ![]() over a

path that is advertised to

over a

path that is advertised to ![]() by a provider or peer.

by a provider or peer.

The last definition is more subtle. We say that an AS ![]() follows a

widest-advertisement policy if the following holds. For a

prefix

follows a

widest-advertisement policy if the following holds. For a

prefix ![]() , if

, if ![]() is ever willing to advertise a primary path to a

neighbor

is ever willing to advertise a primary path to a

neighbor ![]() that it learned from another neighbor

that it learned from another neighbor ![]() , then whenever

, then whenever

![]() knows of any path through

knows of any path through ![]() , it must advertise some path to

, it must advertise some path to ![]() .

Note that this latter path advertised to

.

Note that this latter path advertised to ![]() need not have been

learned from

need not have been

learned from ![]() . Further, note all three policies are consistent;

ASes prefer customer paths, advertise the paths to the widest set of

neighbors and their policies lead to valley-free paths.

. Further, note all three policies are consistent;

ASes prefer customer paths, advertise the paths to the widest set of

neighbors and their policies lead to valley-free paths.

Note that, our proofs hold for any route change for which policies incompliant with the assumptions are not exercised during convergence. With our terminology settled, we now prove several lemmas on our way to the theorems.

The following lemma assumes the widest advertisement policy and shows

that if there is a path through ![]() from an AS

from an AS ![]() to destination

to destination ![]() before

before ![]() goes down, and

goes down, and ![]() has a path to

has a path to ![]() after convergence,

then

after convergence,

then ![]() knows a failover path when

knows a failover path when ![]() goes down.

goes down.

Lemma A.4 If any AS using a down link will have a path to the destination after convergence, then R-BGP guarantees that an AS which is using the down link and adjacent to it knows a failover path when the link fails.

The key to the proof is to show that since each AS in the sequence

![]() advertises a path to destination

advertises a path to destination ![]() to its predecessor at time

to its predecessor at time ![]() , it must also do so at time

, it must also do so at time ![]() .

The proof is by induction on the path, starting at

.

The proof is by induction on the path, starting at ![]() and moving

towards

and moving

towards ![]() . For the base case, we note that since

. For the base case, we note that since ![]() , which

hosts

, which

hosts ![]() , knows a path to

, knows a path to ![]() at time

at time ![]() and advertises a path to

and advertises a path to

![]() at time

at time ![]() , by the widest advertisement policy

, by the widest advertisement policy ![]() must advertise a route to

must advertise a route to ![]() at time

at time ![]() . By assumption, this

path does not use

. By assumption, this

path does not use ![]() (e.g., it could be the one AS hop path to

(e.g., it could be the one AS hop path to

![]() ). For the inductive case,

). For the inductive case, ![]() , where

, where

![]() receives a path from

receives a path from ![]() that does not use

that does not use ![]() , and since it

advertises a path to

, and since it

advertises a path to ![]() at time

at time ![]() ,

, ![]() must also

advertise one at time

must also

advertise one at time ![]() . As before, by assumption the path does not

use

. As before, by assumption the path does not

use ![]() .

.

Now we apply Lemma A.3. Note that by the definition

of ![]() ,

, ![]() does not use a path through

does not use a path through ![]() at time

at time ![]() . Since,

at time

. Since,

at time ![]() ,

, ![]() uses a path through

uses a path through ![]() and knows of a path from

and knows of a path from

![]() that does not, by Lemma A.3, at time

that does not, by Lemma A.3, at time ![]() AS

AS

![]() knows of a failover path that does not use

knows of a failover path that does not use ![]() .

.

![]()

Lemma A.9

Consider a network that is in a

converged state at time ![]() , when a link fails, and converges again at

, when a link fails, and converges again at

![]() . Assuming the valley-free, prefer-customer, and widest-advertisement

policies, at no time between

. Assuming the valley-free, prefer-customer, and widest-advertisement

policies, at no time between ![]() and

and ![]() do the forwarding tables

contain any loops.

do the forwarding tables

contain any loops.

Theorem A.10 Regardless of policies, in a converged state, no AS is deadlocked waiting to send an update, and no AS is forwarding packets along a withdrawn or failover path.

Theorem A.11

Consider a network which is in a converged state at time

![]() , when a link goes down, and converges again at

, when a link goes down, and converges again at ![]() .Assuming

the valley-free, and prefer-customer policies, if an AS

.Assuming

the valley-free, and prefer-customer policies, if an AS ![]() knows a

path to destination

knows a

path to destination ![]() at times

at times ![]() and

and ![]() , then at any time

between

, then at any time

between ![]() and

and ![]() the forwarding tables contain a path from

the forwarding tables contain a path from ![]() to

to ![]() .

.

Recognize that by following Mechanism 3, ![]() will continue to forward

it's own packets unless it recieves a withdrawal from all

neighbors. Thus we need only prove that

will continue to forward

it's own packets unless it recieves a withdrawal from all

neighbors. Thus we need only prove that ![]() has at least one neighbor from whom it never recieves a withdrawal.

has at least one neighbor from whom it never recieves a withdrawal.

To do this, we prove by induction, that between ![]() and

and ![]()

![]() will never receive a withdrawal from

will never receive a withdrawal from ![]() , the neighbor of

, the neighbor of ![]() through

whom

through

whom ![]() will forward at time

will forward at time ![]() . We say the path that

. We say the path that ![]() offers to

offers to ![]() at

at ![]() is

is

![]() , where

, where ![]() and

and ![]() originates

originates ![]() .

.

As the base case it's clear that since ![]() originates

originates ![]() and offers

a path to

and offers

a path to ![]() at

at ![]() , it must also do so from

, it must also do so from ![]() to

to

![]() , by our widest advertisement policy assumption.

Additionally, each AS,

, by our widest advertisement policy assumption.

Additionally, each AS, ![]() , advertises the path from

, advertises the path from ![]() to

to

![]() at

at ![]() and by induction

and by induction ![]() is advertised a path by

is advertised a path by

![]() from

from ![]() to

to ![]() . Thus,

. Thus, ![]() must continuously advertise

some path to

must continuously advertise

some path to ![]() from

from ![]() to

to ![]() by widest-advertisement

policy. Analogously,

by widest-advertisement

policy. Analogously, ![]() must offer

must offer ![]() a path for the entire period

between

a path for the entire period

between ![]() and

and ![]() . Thus we have shown that

. Thus we have shown that ![]() will never

receive a withdrawal from

will never

receive a withdrawal from ![]() between

between ![]() and

and ![]() , and so

, and so ![]() will continue to forward it's own packets.

will continue to forward it's own packets.

![]()

This document was generated using the LaTeX2HTML translator Version 2002-2-1 (1.71)

Copyright © 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996,

Nikos Drakos,

Computer Based Learning Unit, University of Leeds.

Copyright © 1997, 1998, 1999,

Ross Moore,

Mathematics Department, Macquarie University, Sydney.

The command line arguments were:

latex2html -split 0 -no_navigation -white -show_section_numbers paper

The translation was initiated by on 2007-02-28