We survey, evaluate, and compare a variety of approaches to the variable-sized precinct auditing problem, including the SAFE method [11] which is based on theory developed for equal-sized precincts. We introduce new methods such as the negative-exponential method ``NEGEXP'' that select precincts independently for auditing with predetermined probabilities, and the ``PPEBWR'' method that uses a sequence of rounds to select precincts with replacement according to some predetermined probability distribution that may depend on error bounds for each precinct (hence the name PPEBWR: probability proportional to error bounds, with replacement), where the error bounds may depend on the sizes of the precincts, or on how the votes were cast in each precinct.

We give experimental results showing that NEGEXP and PPEBWR can dramatically reduce (by a factor or two or three) the cost of auditing compared to methods such as SAFE that depend on the use of uniform sampling. Sampling so that larger precincts are audited with appropriately larger probability can yield large reductions in expected number of votes counted in an audit.

We also present the optimal auditing strategy, which is nicely representable as a linear programming problem but only efficiently computable for small elections (fewer than a dozen precincts). We conclude with some recommendations for practice.

Post-election audits are an essential tool for ensuring the integrity of election outcomes. They can detect, with high probability, both errors due to machine mis-programming and errors due to malicious manipulation of electronic vote totals. By using statistical samples, they are quite efficient and economical. This paper explores auditing approaches that achieve improved efficiency (sometimes by a factor of two or three, measured in terms of the number of votes counted) over previous methods.

Suppose we have an election with ![]() precincts,

precincts, ![]() , ...,

, ...,

![]() . Let

. Let ![]() denote the number of voters who voted in precinct

denote the number of voters who voted in precinct

![]() ; we call

; we call ![]() the ``size'' of the precinct

the ``size'' of the precinct ![]() . Let the total

number of such voters be

. Let the total

number of such voters be ![]() . Assume without loss of

generality that

. Assume without loss of

generality that

![]() .

.

We focus on auditing precincts as opposed to votes because this is the common form of auditing encountered in practice. If one is interested in sampling votes, then the results in Aslam et al. [1] apply because the votes can be modeled as precincts of equal size (in particular, of size one). In this paper, we are interested in the more general problem, that is, when precincts have different sizes.

Precinct sizes can vary dramatically, sometimes by an order of magnitude or more. See Figure 2.

Methods for auditing elections must, if they are to be efficient and effective, take such precinct size variations into account.

Suppose further that in precinct ![]() we have both electronic records

and paper records for each voter. The electronic records are easy to

tally. For the purposes of this paper, the paper records are used only as a

source of authoritative information when the electronic records are

audited. They may be considered more authoritative since the voters

may have verified them directly. In practice, more care is needed,

since the electronic records could reasonably be judged as more

authoritative in situations where the paper records were obviously

damaged or lost and the electronic records appear undamaged.

we have both electronic records

and paper records for each voter. The electronic records are easy to

tally. For the purposes of this paper, the paper records are used only as a

source of authoritative information when the electronic records are

audited. They may be considered more authoritative since the voters

may have verified them directly. In practice, more care is needed,

since the electronic records could reasonably be judged as more

authoritative in situations where the paper records were obviously

damaged or lost and the electronic records appear undamaged.

Auditing is desirable since a malicious party, the ``adversary,'' may have manipulated some of the electronic tallies so that a favored candidate appears to have won the election. It is also possible for a simple software bug caused the electronic tallies to be inaccurate. However, we focus on detecting malicious adversarial behavior because it is the more challenging task.

A precinct can be ``audited'' by re-counting by hand the paper records of that precinct to confirm that they match the electronic totals for that precinct. We ignore here the important fact that hand-counting may be inaccurate, and assume that any discrepancies are due to fraud on the part of the adversary. In practice, the discrepancy might have to be larger than some prespecified threshold to trigger a conclusion of fraud in that precinct.

See the overviews [8,13,6] for information about current election auditing procedures. In this paper we ignore many of the complexities of real elections; these complexities are addressed in other papers. We do so in order to focus on our central issue: how to select a sample of precincts to audit when the precincts have different sizes. See Neff [12], Cordero et al. [5], Saltman [17], Dopp et al. [7], and Aslam et al. [1], for additional discussion of the mathematics of auditing, and additional references to the literature.

We begin with an overview of the auditor's general approach in Section 2. In Section 3 we review the adversary's objectives and capabilities. Section 4 then reviews the auditor's strategy. Some known results for auditing when all precincts have equal size are discussed in Section 5. We next review in Section 6 the ``SAFE'' method, which deals with variable-sized precincts using the mathematics developed for equal-sized precincts, by first deriving a lower bound on the number of precincts that must have been corrupted, if the election outcome was changed. Section 7 introduces basic auditing methods, where each precinct is chosen independently according to a precomputed probability distribution. A particularly attractive basic auditing method is introduced in Section 8; this method is called the ``negative-exponential'' (NEGEXP) auditing method. We then consider audits where precincts are not chosen independently. Section 9 introduces the method of sampling with probability proportional to error bounds, with replacement (PPEBWR); a special case of this procedure is PPSWR, ``sampling with probability proportional to size, with replacement.'' Section 10 discusses vote-dependent auditing, where the probability of auditing a precinct depends on the actual vote counts for each candidate. Section 11 gives experimental results using data from Ohio and Minnesota. Section 12 presents a method based on linear programming for determining an optimal auditing procedure, which unfortunately appears to be computationally too expensive for practical use. Section 13 closes with discussion and recommendations for practice.

We assume here that the election is a winner-take-all (plurality)

election from a field of ![]() candidates.

candidates.

After the election, the auditor randomly selects a sample of precincts for the post-election audit. In each selected precinct the paper ballots are counted by hand; the totals obtained in this manner are then compared with the electronic tallies. We assume that the paper ballots are maintained securely and that they can be accurately counted during the post-election audit.

The auditor wishes to assure himself (and everyone else) that the level of error and/or fraud in the election is likely to be low or nonexistent, or at least insufficient to have changed the election outcome. If the audit finds no (significant) discrepancies between the electronic and paper tallies, the auditor announces that no fraud was discovered, and the election results may be certified by the appropriate election official.

However, if significant discrepancies are found between the electronic and paper tallies, additional investigations may be appropriate. For example, state law may require a full recount of the paper ballots. Stark [19] gives procedures for incrementally auditing larger and larger samples when discrepancies are found, until the desired level of confidence in the election outcome is achieved.

When planning the audit, the auditor knows the number ![]() of reported (electronic)

votes for each candidate

of reported (electronic)

votes for each candidate ![]() in precinct

in precinct ![]() , and

the total size

, and

the total size ![]() (total number of votes cast) of each

precinct

(total number of votes cast) of each

precinct ![]() . The auditor also knows the reported margin of victory, denoted

. The auditor also knows the reported margin of victory, denoted

![]() of the winning candidate over the runner-up--this is the

difference between the number of votes reported for the apparently

victorious candidate and the number of votes reported for the

runner-up. Larger audits are appropriate when the margins of victory

are smaller (see, e.g., Norden et al. [13]).

of the winning candidate over the runner-up--this is the

difference between the number of votes reported for the apparently

victorious candidate and the number of votes reported for the

runner-up. Larger audits are appropriate when the margins of victory

are smaller (see, e.g., Norden et al. [13]).

We believe that the audit should be designed to achieve a pre-specified level of confidence in the election outcome, i.e., when an election is ultimately certified, one should be confident, in a statistically quantifiable manner, that the election outcome is correct. It is the correct (and efficient) approach. Naive methods that audit a fixed fraction of precincts tend to waste money when the margin of victory is large, and provide poor confidence in the election outcome when the margin of victory is small. See McCarthy et al. [11].

In order to ensure that an election outcome is correct, one must

be able to detect levels of fraud sufficient to change the outcome

of the election.

We thus assume the auditor desires to test at a certain

significance level ![]() that error or fraud is unlikely to have affected

the election outcome. A well-designed audit can reduce the likelihood

that significant fraud or error has gone undetected. A significance

level of

that error or fraud is unlikely to have affected

the election outcome. A well-designed audit can reduce the likelihood

that significant fraud or error has gone undetected. A significance

level of ![]() means that the chance that error large enough

to have changed the election outcome will go undetected is one in

twenty.

means that the chance that error large enough

to have changed the election outcome will go undetected is one in

twenty.

Let ![]() denote the ``confidence level'' of the audit, where

denote the ``confidence level'' of the audit, where

![]() Thus, a test at significance level

Thus, a test at significance level ![]() provides a confidence level

of

provides a confidence level

of ![]() . This is independent of the way fraud was

committed (at the level of the machine, precinct, vote or other) because we only model the overall fraud in our formulas.

We follow Stark [19] in adopting as our null hypothesis

``the (electronic) election outcome is incorrect'', so that

. This is independent of the way fraud was

committed (at the level of the machine, precinct, vote or other) because we only model the overall fraud in our formulas.

We follow Stark [19] in adopting as our null hypothesis

``the (electronic) election outcome is incorrect'', so that ![]() is an upper bound on the probability that the null hypothesis will be

rejected (i.e. that the electronic outcome will be accepted) when the

null hypothesis is true (the electronic outcome is wrong).

is an upper bound on the probability that the null hypothesis will be

rejected (i.e. that the electronic outcome will be accepted) when the

null hypothesis is true (the electronic outcome is wrong).

Depending on the precinct sizes, the reported votes for each candidate, and thus the reported margin of victory, the auditor determines how to select an appropriately-sized random sample of precincts for auditing.

We explore three methods by which the auditor chooses a sample:

If all precincts have the same size, one may measure the cost of performing an audit in terms of the (expected) number of precincts audited. If precincts have a variety of sizes, the (expected) number of votes counted appears to be a better measure of auditing cost. The auditing cost is most reasonably measured in person-hours, which will be proportional to the number of votes recounted. The overall cost may have a constant additive term for each precinct (a setup cost), but this should be small compared to the cost to audit the votes.

We assume the adversary wishes to corrupt enough of the electronic

tallies so that his favored candidate

wins the most votes according to the reported electronic tallies.

Without loss

of generality, we'll let candidate ![]() be the adversary's favored

candidate. The adversary tries to do his manipulations in such a way as to

minimize the chance that his changes to the electronic tallies

will be caught during the post-election audit.

be the adversary's favored

candidate. The adversary tries to do his manipulations in such a way as to

minimize the chance that his changes to the electronic tallies

will be caught during the post-election audit.

Let ![]() denote the actual number of (paper) votes for

candidate

denote the actual number of (paper) votes for

candidate ![]() in precinct

in precinct ![]() , and let

, and let ![]() denote the

reported number of (electronic) votes for candidate

denote the

reported number of (electronic) votes for candidate ![]() in

precinct

in

precinct ![]() . With no adversarial manipulation, we will have

. With no adversarial manipulation, we will have

![]() for all

for all ![]() and

and ![]() . We ignore in this paper small explainable

discrepancies that can be handled by slight modifications to the

procedures discussed here.

. We ignore in this paper small explainable

discrepancies that can be handled by slight modifications to the

procedures discussed here.

We thus have for all ![]() :

:

![]() the total number of paper votes cast in precinct

the total number of paper votes cast in precinct ![]() is equal to the

number of electronic votes cast in precinct

is equal to the

number of electronic votes cast in precinct ![]() ; this number is

; this number is ![]() ,

the ``size'' of precinct

,

the ``size'' of precinct ![]() . (Our techniques can perhaps be extended to handle

situations where such reconciliation is not done; we have not yet examined

this question closely.)

. (Our techniques can perhaps be extended to handle

situations where such reconciliation is not done; we have not yet examined

this question closely.)

Let ![]() denote the total actual number of votes for candidate

denote the total actual number of votes for candidate ![]() :

:

![]() and let

and let ![]() denote the total number of votes reported for candidate

denote the total number of votes reported for candidate ![]() :

:

![]() The adversary's favored candidate, candidate

The adversary's favored candidate, candidate ![]() , will be the

winner of the electronic report totals if

, will be the

winner of the electronic report totals if

![]()

We assume for now that the election is really between candidate ![]() and candidate

and candidate ![]() , so that the adversary's objective is to ensure that

candidate

, so that the adversary's objective is to ensure that

candidate ![]() is reported to win the election and that candidate

is reported to win the election and that candidate ![]() is not.

There may be other candidates in the race, but for the moment we'll

assume that they are minor candidates. It is also convenient to

consider ``invalid'' and ``undervote'' to be such ``minor candidates''

when doing the tallying.

is not.

There may be other candidates in the race, but for the moment we'll

assume that they are minor candidates. It is also convenient to

consider ``invalid'' and ``undervote'' to be such ``minor candidates''

when doing the tallying.

The adversary can manipulate the election in favor of his or her desired candidate by

shifting the electronic tallies from one candidate to another. He or she might

move votes from some candidate to candidate ![]() . Or move votes from

candidate

. Or move votes from

candidate ![]() to some other candidate. These manipulations can change

the election outcome, and yield a false ``margin of victory.'' The

margin of victory plays a key role in our analysis.

to some other candidate. These manipulations can change

the election outcome, and yield a false ``margin of victory.'' The

margin of victory plays a key role in our analysis.

Let ![]() denote the ``actual margin of victory'' (in votes) of

candidate

denote the ``actual margin of victory'' (in votes) of

candidate ![]() over candidate

over candidate ![]() :

:

![]() Let

Let ![]() denote the ``reported margin of victory'' (in votes) for

candidate

denote the ``reported margin of victory'' (in votes) for

candidate ![]() over candidate

over candidate ![]() :

:

![]() Note that

Note that ![]() will be known to the auditor at the beginning of the audit,

but that

will be known to the auditor at the beginning of the audit,

but that ![]() will not.

will not.

The adversary may be in a situation initially where ![]() (i.e.

(i.e. ![]() ); that is,

his or her favored candidate, candidate

); that is,

his or her favored candidate, candidate ![]() , has lost to candidate

, has lost to candidate ![]() . The

adversary must, in order to change the election outcome, manipulate

the (electronic) votes so that

. The

adversary must, in order to change the election outcome, manipulate

the (electronic) votes so that ![]() (i.e. so that

(i.e. so that ![]() ) and do so in a way that goes undetected.

) and do so in a way that goes undetected.

The ``error'' ![]() in favor of candidate

in favor of candidate ![]() introduced in the margin of victory computation

in precinct

introduced in the margin of victory computation

in precinct ![]() by the adversary's manipulations

is (in votes):

by the adversary's manipulations

is (in votes):

An upper bound on the amount by which the adversary can improve

the margin of victory in favor of his candidate in precinct ![]() is:

is:

Let ![]() denote the total error (in votes, from all precincts)

introduced in the margin of victory computation by the adversary:

denote the total error (in votes, from all precincts)

introduced in the margin of victory computation by the adversary:

![]() Clearly,

Clearly,

![]() That is, the reported margin of victory is equal to the actual margin of victory,

plus the error introduced by the adversary.

That is, the reported margin of victory is equal to the actual margin of victory,

plus the error introduced by the adversary.

The adversary has to introduce enough error ![]() so that the reported

margin of victory

so that the reported

margin of victory ![]() becomes positive, even though the initial

(actual) margin of victory

becomes positive, even though the initial

(actual) margin of victory ![]() is negative. Thus, the

amount of error introduced satisfies both of the inequalities:

is negative. Thus, the

amount of error introduced satisfies both of the inequalities:

![]() and

and

![]() The second inequality is of most interest to the auditor, since

at the beginning of the audit the auditor knows

The second inequality is of most interest to the auditor, since

at the beginning of the audit the auditor knows ![]() but

not

but

not ![]() . For convenience, we shall use

. For convenience, we shall use

![]() in the sequel, and let

in the sequel, and let ![]() denote the fraction of votes represented

by the margin of victory:

denote the fraction of votes represented

by the margin of victory:

![]() (recall that

(recall that ![]() denotes the total number of votes cast:

denotes the total number of votes cast: ![]() ).

).

We assume here that the adversary wishes to change the election

outcome while minimizing the probability of detection--that

is, while minimizing the chance that one or more of the precincts

chosen have been corrupted. If the post-election audit fails to find any error, the adversary's

candidate might be declared the winner, while in fact some other

candidate (e.g. candidate ![]() ) actually should have won.

) actually should have won.

The adversary might not be willing to corrupt all available votes in a

precinct; this would generate too much suspicion.

Dopp and Stenger [7] suggest that the adversary might

not dare to flip more than a fraction ![]() of the votes in a precinct.

The value

of the votes in a precinct.

The value ![]() is also denoted WPM in the literature, and called

the Within-Precinct-Miscount.

is also denoted WPM in the literature, and called

the Within-Precinct-Miscount.

Our auditing methods in this paper depend heavily on the use of such upper bounds

on ![]() , that is, on the maximum amount by which the adversary can change the margin of victory in each precinct. We use

, that is, on the maximum amount by which the adversary can change the margin of victory in each precinct. We use ![]() to denote such an upper bound on

to denote such an upper bound on ![]() .

Following Dopp and Stenger, we would have as an upper bound

.

Following Dopp and Stenger, we would have as an upper bound ![]() for

for

![]() :

:

We may also presume that the adversary knows the general form of the auditing method. Indeed, the auditing method may be mandated by law, or described in public documents. While the adversary may not know which specific precincts will be chosen for auditing, because they are determined by rolls of the dice or other random means, the adversary is assumed to know the method by which those precincts will be chosen, and thus to know the probability that any particular precinct will be chosen for auditing.

We let ![]() denote the set of corrupted precincts, and

let

denote the set of corrupted precincts, and

let ![]() denote the number

denote the number

![]() of corrupted precincts.

In this discussion, we assumed that ``reconciliation'' is performed when the election is

over, confirming that the number of votes recorded electronically is

equal to the number of votes recorded on paper; an adversary would

presumably not try to make these totals differ, but only shift

the electronic tallies to favor his candidate at the expense of

other candidates. If ``reconciliation'' is not performed and an adversary reduces the number of

votes cast in a precinct that is, say, known to be favorable to the opponent, our techniques can still discover the fraud

within the desired confidence level. This happens if the resulting change in the margin of victory (expressed in votes) is at most the error bound

of corrupted precincts.

In this discussion, we assumed that ``reconciliation'' is performed when the election is

over, confirming that the number of votes recorded electronically is

equal to the number of votes recorded on paper; an adversary would

presumably not try to make these totals differ, but only shift

the electronic tallies to favor his candidate at the expense of

other candidates. If ``reconciliation'' is not performed and an adversary reduces the number of

votes cast in a precinct that is, say, known to be favorable to the opponent, our techniques can still discover the fraud

within the desired confidence level. This happens if the resulting change in the margin of victory (expressed in votes) is at most the error bound ![]() of the resulting precinct. This condition holds when the adversary decreases the total number of votes cast in the precinct by at most a factor of

of the resulting precinct. This condition holds when the adversary decreases the total number of votes cast in the precinct by at most a factor of ![]() (

(![]() for

for ![]() ). Arguably, if the final number of votes cast is reduced even more, such a dramatic corruption should be detected.

). Arguably, if the final number of votes cast is reduced even more, such a dramatic corruption should be detected.

There are many different ways to perform an audit; see Norden et al. [13] for discussion. In this paper we focus on how the sample is selected; an auditing method is one of following five types:

A fixed audit determines the amount of auditing to do by fiat--e.g., it selects a fixed number of precincts (or votes) to be counted (or perhaps a fixed percentage, instead of a fixed number). It does not pay attention to the precinct sizes, the reported margin of victory, or the reported vote counts. Fixed audits are simple to understand, but are frequently very costly or statistically weak.

If an audit is not a fixed audit, it is an adjustable audit--the size of the audit is adjustable according to various parameters of the election. There are four types of adjustable audits, in order of increasing utilization of available parameter information.

The first (and simplest) type of adjustable audit is a

margin-dependent audit. Here the selection of precincts to be

audited depends only on the reported margin of victory ![]() . An

election that is a landslide (with a very large margin of victory)

results in smaller audit sample sizes than an election that is tight.

. An

election that is a landslide (with a very large margin of victory)

results in smaller audit sample sizes than an election that is tight.

In order for an audit to provide a guaranteed level of confidence in the election outcome while still being efficient (it does not audit significantly more votes/precincts than needed), it must be margin-dependent (or better). The remaining three types of adjustable audits are refinements of the margin-dependent audit. Margin-dependent audits have been proposed by Saltman [17], Lobdill [10], Dopp and Stenger [7], McCarthy et al. [11], among others.

The second type of adjustable audit is a size-dependent audit.

Here the selection of precincts to be audited depends not only on the

reported margin of victory ![]() but also on the precinct sizes

but also on the precinct sizes ![]() .

A size-dependent audit audits larger precincts with

higher probability and audits small precincts with smaller probability.

This reflects the fact that the larger precincts are

``juicier targets'' for the adversary. Overall, the total amount

of auditing work performed may easily be less than for an audit that

does not take precinct sizes into account.

.

A size-dependent audit audits larger precincts with

higher probability and audits small precincts with smaller probability.

This reflects the fact that the larger precincts are

``juicier targets'' for the adversary. Overall, the total amount

of auditing work performed may easily be less than for an audit that

does not take precinct sizes into account.

The third type of adjustable audit is a vote-dependent audit.

Here the selection of precincts to be audited depends not only on the

reported margin of victory ![]() and the precinct sizes

and the precinct sizes ![]() ,

but also on the reported vote counts

,

but also on the reported vote counts ![]() .

A vote-dependent audit can reflect the intuition that if precinct

.

A vote-dependent audit can reflect the intuition that if precinct ![]() reports more votes for candidate

reports more votes for candidate ![]() (the reported winner)

than precinct

(the reported winner)

than precinct ![]() reports, then precinct

reports, then precinct ![]() should perhaps

be audited with higher probability, since it may have experienced

a larger amount of fraud. See Section 10;

also see Calandrino et al. [3].

should perhaps

be audited with higher probability, since it may have experienced

a larger amount of fraud. See Section 10;

also see Calandrino et al. [3].

The fourth type of adjustable audit is a history-dependent audit.

Here the selection of precincts to be audited depends not only on the reported

margin of victory ![]() , the precinct sizes

, the precinct sizes ![]() , and the reported

vote counts

, and the reported

vote counts ![]() , but also on records of similar data for previous elections.

A precinct whose reported vote counts are at odds with those from previous

similar elections becomes more likely to be audited.

, but also on records of similar data for previous elections.

A precinct whose reported vote counts are at odds with those from previous

similar elections becomes more likely to be audited.

Here we consider what we call an

error-bound-dependent audit, where the

auditor computes for each precinct ![]() an error bound

an error bound ![]() on the error (change in margin of

victory) that the adversary could have made in that precinct.

An error-dependent audit is a special case of

a size-dependent audit, if the error bound for precinct

on the error (change in margin of

victory) that the adversary could have made in that precinct.

An error-dependent audit is a special case of

a size-dependent audit, if the error bound for precinct ![]() depends only the size

depends only the size ![]() of the precinct, as in the

Linear Error Bound Assumption of equation (2)

where the error bound is simply proportional to the precinct size. The linear error bound assumption leads, for example, to sampling

strategies of the form ``probability proportional size,'' as we shall

see, since our ``probability proportional to error bound'' strategy

becomes ``probability proportional to size'' when ``error bound is

proportional to size.''

of the precinct, as in the

Linear Error Bound Assumption of equation (2)

where the error bound is simply proportional to the precinct size. The linear error bound assumption leads, for example, to sampling

strategies of the form ``probability proportional size,'' as we shall

see, since our ``probability proportional to error bound'' strategy

becomes ``probability proportional to size'' when ``error bound is

proportional to size.''

However, the error-dependent audit could be a special case of

a vote-dependent audit, if the error bound ![]() depends on

the votes cast in precinct

depends on

the votes cast in precinct ![]() . We explore this possibility

in Section 10. In any case, it

is useful to formally ``decouple'' the

error bound from the precinct size; we let

. We explore this possibility

in Section 10. In any case, it

is useful to formally ``decouple'' the

error bound from the precinct size; we let

![]() denote the sum of these error bounds.

denote the sum of these error bounds.

The post-election audit involves the following steps.

We do not discuss triggers and escalation in this paper, although such discussion is very important and needs to be included in any complete treatment of post-election auditing (see Stark [19]).

How should the auditor select precincts to audit? The auditor wishes to maximize the probability of detection:

the probability that the auditor audits at least one bad precinct

(with nonzero error ![]() ), if there is sufficient error to have

changed the election outcome. The auditor's method should be randomized, as is usual in game

theory; this unpredictability prevents the adversary from knowing in

advance which precincts will be audited.

), if there is sufficient error to have

changed the election outcome. The auditor's method should be randomized, as is usual in game

theory; this unpredictability prevents the adversary from knowing in

advance which precincts will be audited.

We first review auditing procedures to use when all precincts have the same size. We then proceed to discuss the case of interest in this paper, that is, when precincts have a variety of sizes.

This section briefly reviews the situation when all ![]() of the precincts have the same size

of the precincts have the same size ![]() (so

(so ![]() ).

We adopt the Linear Error Bound Assumption (

).

We adopt the Linear Error Bound Assumption (![]() )

of equation (2)

in this section. Let

)

of equation (2)

in this section. Let ![]() denote the number of precincts that have been corrupted. Since an adversary who changed the election outcome must have

introduced sufficient error,

denote the number of precincts that have been corrupted. Since an adversary who changed the election outcome must have

introduced sufficient error,

![]() so that (see Dopp et al. [7])

so that (see Dopp et al. [7])

![]() is the minimum number of precincts the adversary could have corrupted.

is the minimum number of precincts the adversary could have corrupted.

When all precincts have the same size, the auditor should pick an

appropriate number ![]() of distinct precincts uniformly at random to

audit. See Neff [12], Saltman [17], or Aslam et

al. [1] for discussion and procedures for calculating

appropriate audit sample sizes.

of distinct precincts uniformly at random to

audit. See Neff [12], Saltman [17], or Aslam et

al. [1] for discussion and procedures for calculating

appropriate audit sample sizes.

The probability of detecting at least one corrupted precinct in

a sample of size ![]() is

is

![]() By choosing

By choosing ![]() so that

so that

Rivest [16]

suggests approximating equation (3)

by a ``Rule of Thumb'':

![]() one over the (fractional) margin of victory

one over the (fractional) margin of victory ![]() . For

equal-sized precincts (with

. For

equal-sized precincts (with ![]() ), this gives

remarkably good results, corresponding to a confidence

level of at least

), this gives

remarkably good results, corresponding to a confidence

level of at least ![]() .

.

The ``SAFE'' auditing method by McCarthy et al. [11] is perhaps the best-known approach to auditing elections; it adapts the approach for handling equal-sized precincts discussed above to handle variable-sized precincts.

In 2006 Stanislevic [18] presented a conservative way of handling precincts of different sizes; this approach was also developed independently by Dopp et al. [7]. This method is the basis for the SAFE auditing procedure.

It assumes that the adversary corrupts the larger precincts first,

yielding a lower bound on the number ![]() of precincts that

must have been corrupted if the election outcome was changed. The

auditor can then use

of precincts that

must have been corrupted if the election outcome was changed. The

auditor can then use ![]() in an auditing method that

samples precincts uniformly. More precisely, the auditor knows that

if the adversary changed the election outcome, he or she must have corrupted

at least

in an auditing method that

samples precincts uniformly. More precisely, the auditor knows that

if the adversary changed the election outcome, he or she must have corrupted

at least ![]() precincts, where

precincts, where ![]() is the least integer

such that

is the least integer

such that

![]() (Recall our assumption that

(Recall our assumption that

![]() .)

Then the auditor draws a sample of size

.)

Then the auditor draws a sample of size ![]() precincts uniformly, where

precincts uniformly, where ![]() satisfies (3); this ensures a probability

of at least

satisfies (3); this ensures a probability

of at least ![]() that a corrupted precinct will be sampled,

if the adversary produced enough fraud to have changed the election outcome.

that a corrupted precinct will be sampled,

if the adversary produced enough fraud to have changed the election outcome.

This section reviews ``basic'' auditing methods, where each precinct is audited independently with a precinct-specific probability determined by the auditor. Many interesting auditing procedures are basic auditing procedures. We try restricting our attention to ``basic'' methods in an effort to make some of the math simpler; although we shall see in Section 9 that the math is actually fairly simple for some non-basic methods.

This section assumes that the auditor will audit each precinct ![]() independently with some probability

independently with some probability ![]() , where

, where ![]() . The

auditing method is thus determined by the vector

. The

auditing method is thus determined by the vector

![]() . The probabilities

. The probabilities ![]() sum to the

expected number of precincts audited; they do not normally

sum to

sum to the

expected number of precincts audited; they do not normally

sum to ![]() because commonly we audit more than one precinct. The expected workload (i.e., the

expected number of votes to be counted) is

because commonly we audit more than one precinct. The expected workload (i.e., the

expected number of votes to be counted) is

| (4) |

In the basic auditing procedures we describe in this paper, the chance

of auditing a precinct is independent of the error introduced into

that precinct by the adversary. Thus, we can assume that the

adversary makes the maximum change possible in each corrupted

precinct: ![]() . This helps the adversary reduce the number

of precincts corrupted and reduces the chance of him being caught

during an audit.

. This helps the adversary reduce the number

of precincts corrupted and reduces the chance of him being caught

during an audit.

A basic auditing method is not difficult to implement in practice in

an open and transparent way. A table is printed giving for each

precinct ![]() its corresponding probability

its corresponding probability ![]() of being audited.

For each precinct

of being audited.

For each precinct ![]() ,

four ten-sided dice are rolled to give a four-digit decimal

number

,

four ten-sided dice are rolled to give a four-digit decimal

number

![]() . Here

. Here ![]() is the digit from the

is the digit from the ![]() -th

dice roll. If

-th

dice roll. If ![]() , then precinct

, then precinct ![]() is audited; otherwise

it is not. The probability table and a video-tape of the dice-rolling

are published. See [5] for more discussion on the

use of dice.

is audited; otherwise

it is not. The probability table and a video-tape of the dice-rolling

are published. See [5] for more discussion on the

use of dice.

One very nice aspect of basic auditing methods is that we can easily

compute the exact significance level for ![]() .

Given

.

Given ![]() , one can use a dynamic programming algorithm to

compute the probability of detecting an adversary who changes the

margin by

, one can use a dynamic programming algorithm to

compute the probability of detecting an adversary who changes the

margin by ![]() votes or more. This algorithm, and applications of it

to heuristically compute optimal basic auditing strategies, are

given by Rivest [15].

votes or more. This algorithm, and applications of it

to heuristically compute optimal basic auditing strategies, are

given by Rivest [15].

This section presents the ``negative exponential'' auditing method NEGEXP, which appears to have near-optimal efficiency, and which is quite simple and elegant. Depending on the details of the audit being performed, either NEGEXP or the PPEBWR of the next section may be the better practical choice.

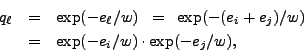

The ``negative-exponential'' auditing method (NEGEXP) is a heuristic basic auditing method. Intuitively, the probability that a precinct is audited is one minus a negative exponential function of the error bound for a precinct. See Figure 1.

The ``value'' to the adversary of corrupting precinct ![]() is assumed

to be

is assumed

to be ![]() , the known upper bound on the amount of error (in the

margin of victory) that can be introduced in precinct

, the known upper bound on the amount of error (in the

margin of victory) that can be introduced in precinct ![]() . In a

typical situation

. In a

typical situation ![]() might be proportional to

might be proportional to ![]() ; this is the

Linear Error Bound Assumption.

; this is the

Linear Error Bound Assumption.

Intuitively, the auditor wants to make the adversary's risk of detection grow with the ``value'' a precinct has to the adversary; this motivates the adversary to leave untouched those precincts with large error bounds. The adversary thus ends up having to corrupt a larger number of smaller precincts, which increases his or her chance of being caught in a random sample.

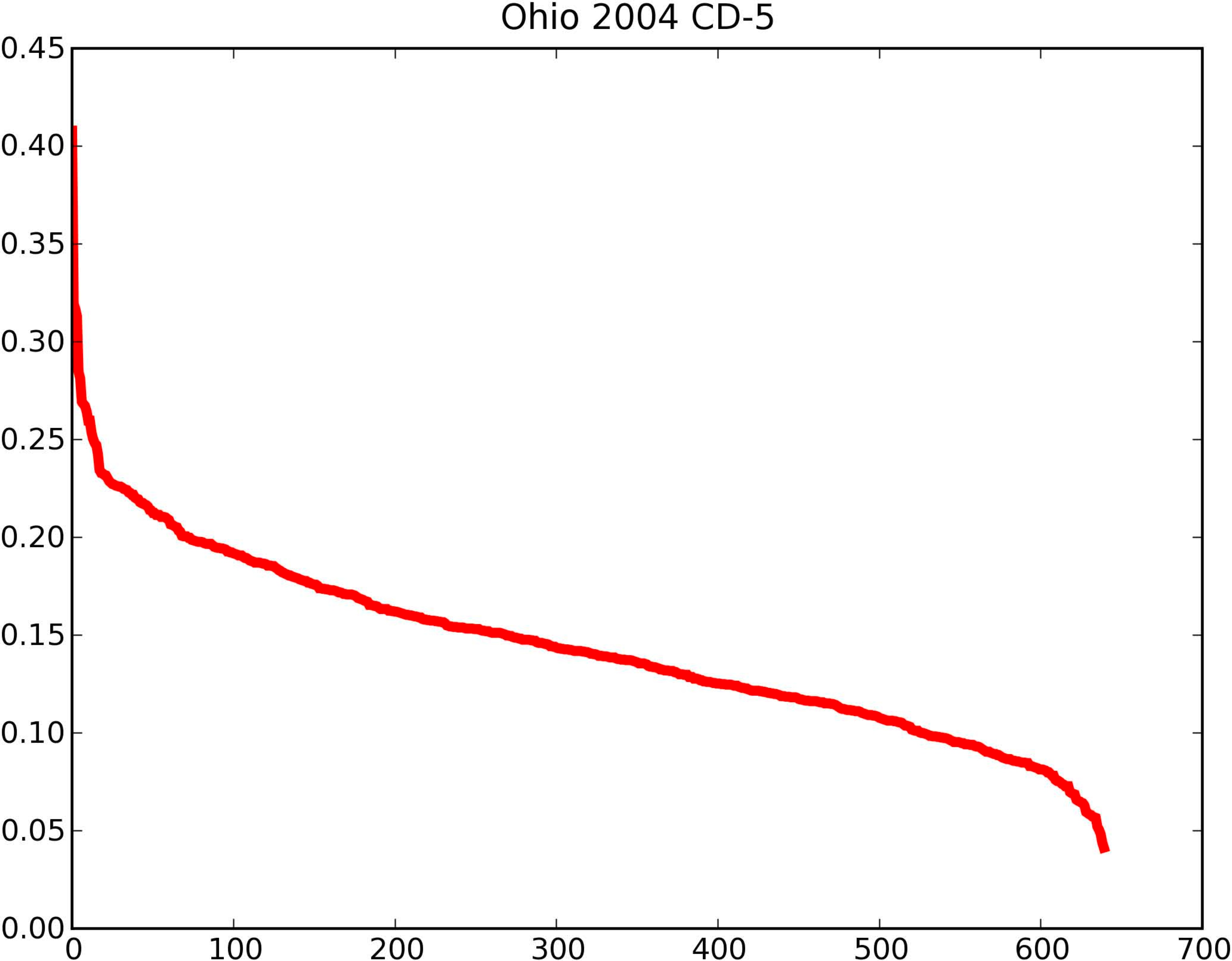

The motivation for the NEGEXP method is the following strategy for

the auditor: determine auditing probabilities so that

the chance of auditing at least one precinct from the set of corrupted precincts

depends only on the total error bound of that set of precincts.

For example, the adversary will then be

indifferent between corrupting a single precinct with error bound

![]() or corrupting two precincts with respective error bounds

or corrupting two precincts with respective error bounds

![]() and

and ![]() . The chance of being caught on

. The chance of being caught on

![]() or being caught on at least one of

or being caught on at least one of ![]() and

and ![]() should be the same.

should be the same.

This implies that the auditor does not audit

each ![]() with probability

with probability ![]() , where

, where

Our NEGEXP auditing method thus yields, from (5),

With the NEGEXP method, as the error bound ![]() increases, the probability of auditing

increases, the probability of auditing ![]() increases, starting off

at

increases, starting off

at ![]() for

for ![]() and increasing as

and increasing as ![]() increases, and levelling

off approaching

increases, and levelling

off approaching ![]() asymptotically for large

asymptotically for large ![]() . The chance of

auditing

. The chance of

auditing ![]() passes

passes

![]() as

as ![]() exceeds

exceeds ![]() .

.

|

The value ![]() can be thought of as approximating a ``threshold''

value: precincts with

can be thought of as approximating a ``threshold''

value: precincts with ![]() larger than

larger than ![]() have a fairly high probability of

being audited, while those smaller than

have a fairly high probability of

being audited, while those smaller than ![]() have a smaller chance of

being audited. As

have a smaller chance of

being audited. As ![]() decreases, the auditing gets more stringent:

more precincts are likely to be audited.

decreases, the auditing gets more stringent:

more precincts are likely to be audited.

An auditor may choose to use the NEGEXP auditing

method of equation (6), and choose ![]() to achieve an audit with a given significance level.

to achieve an audit with a given significance level.

The design of NEGEXP makes this easy, since

NEGEXP has the property

that for any set ![]() of precincts that the adversary may choose to

corrupt satisfying

of precincts that the adversary may choose to

corrupt satisfying

![]() the chance of detection is at least

the chance of detection is at least

This holds no matter what set of precincts, ![]() , the adversary chooses.

, the adversary chooses.

How can an auditor audit enough to achieve a given significance level? The relationship of equation (7)

gives a very nice way for the auditor

to choose ![]() : by choosing

: by choosing

| (9) |

| (10) |

This completes our description of the NEGEXP auditing method. Section 11 presents experimental results for this method. In the next section, we describe a different method (PPEBWR), which turns out to be nearly identical (but slightly better) in efficiency to the NEGEXP method, and which in some circumstances may be easier to work with, although it is somewhat less flexible.

This section presents the ``PPEBWR'' (sampling with probability proportional to error bound, with replacement) auditing strategy. It is simple to implement, and does at least as well as the NEGEXP method. Indeed, the PPEBWR is an excellent method in many respects, and we recommend its use, although the NEGEXP may be more useful when additional flexibility is required (e.g. having multiple races with overlapping jurisdictions).

Consider auditing an election with non-uniform error bounds

![]() where

where

![]() . Let

. Let ![]() be the

(minimum) level of error one wishes to detect;

be the

(minimum) level of error one wishes to detect; ![]() is the margin of

victory. Consider the following sampling-with-replacement procedure.

Form a sampling distribution

is the margin of

victory. Consider the following sampling-with-replacement procedure.

Form a sampling distribution ![]() over the precincts:

over the precincts:

While the per-round probabilities ![]() are

proportional to size, the overall probabilities

are

proportional to size, the overall probabilities ![]() are generally

not: note that as

are generally

not: note that as ![]() gets large the overall

probability of selection of each precinct approaches

gets large the overall

probability of selection of each precinct approaches ![]() . Actually,

the overall probabilities

. Actually,

the overall probabilities ![]() turn out to be nearly identical (but slightly

less) than those computed by the NEGEXP method.

turn out to be nearly identical (but slightly

less) than those computed by the NEGEXP method.

We now show how to determine the number ![]() of rounds for a desired

audit significance level

of rounds for a desired

audit significance level ![]() . Any set of precincts whose

total error bound is at least

. Any set of precincts whose

total error bound is at least ![]() will have probability weight at

least

will have probability weight at

least ![]() . Similar to the derivation in (12) where we replace

. Similar to the derivation in (12) where we replace ![]() by

by ![]() , the probability that at least one such precinct is detected is at least

, the probability that at least one such precinct is detected is at least

We can show that the probability ![]() with which any

given precinct

with which any

given precinct ![]() is audited is slightly smaller than the

negative-exponential audit probability leading to a slightly more efficient

sample size. Our experimental results have

shown that the difference in audit sizes of the two methods is nevertheless small.

is audited is slightly smaller than the

negative-exponential audit probability leading to a slightly more efficient

sample size. Our experimental results have

shown that the difference in audit sizes of the two methods is nevertheless small.

The costs of the PPEBWR strategy are easy to compute.

The expected number of precincts audited is

![]() and the expected number of votes audited is

and the expected number of votes audited is

![]()

Note that in both NEGEXP and PPEBWR the confidence level achieved is at least

![]() no matters what strategy the adversary follows (within the assumptions made). This includes the best possible strategy in which the adversary is aware of our auditing scheme and minimizes his detection probability; he/she still cannot lower this probability beyond

no matters what strategy the adversary follows (within the assumptions made). This includes the best possible strategy in which the adversary is aware of our auditing scheme and minimizes his detection probability; he/she still cannot lower this probability beyond ![]() .

.

This section drops the assumption that

error bounds are proportional to precinct size,

i.e., that

![]() How else can the auditor obtain a bound on the

error? Instead of having a size-dependent audit, he or she may

have a vote-dependent audit, using the fact that

How else can the auditor obtain a bound on the

error? Instead of having a size-dependent audit, he or she may

have a vote-dependent audit, using the fact that

![]() if

if

If we are unsure who the ``runner-up'' is,

we can take the maximum bound over any such ``runner-up'':

![]() Note that the ``candidates'' used for the ``invalid'' or ``undervote''

tallies should be excluded--they cannot be winners or runners-up.

These bounds

Note that the ``candidates'' used for the ``invalid'' or ``undervote''

tallies should be excluded--they cannot be winners or runners-up.

These bounds ![]() will usually be larger than those obtained via a

within-shift bound

will usually be larger than those obtained via a

within-shift bound ![]() , thus giving worse results.

However, in a two-candidate race if a precinct votes almost entirely

for the electronic runner-up, the new bound may be smaller.

, thus giving worse results.

However, in a two-candidate race if a precinct votes almost entirely

for the electronic runner-up, the new bound may be smaller.

Stark [19, Section 3.1] suggests ``pooling'' several obviously losing candidates to create an obviously losing ``pseudo-candidate'' to reduce the error bounds; this can also be applied here.

We illustrate and compare the previously described methods for handling variable-sized precincts using data from Ohio. These results show that taking precinct size into account (e.g. by using NEGEXP or PPSWR) can result in dramatic reductions in auditing cost, compared to methods (such as SAFE) that do not.

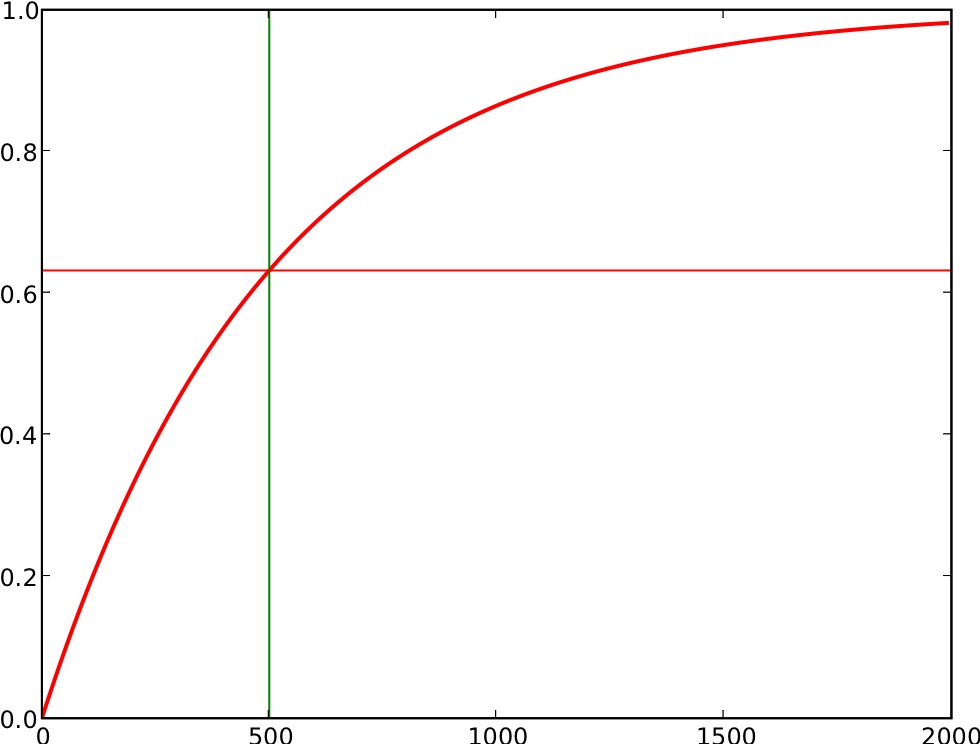

Mark Lindeman kindly supplied a dataset of precinct vote counts (sizes)

for the Ohio congressional district 5 race (OH-05) in 2004.

A total of ![]() votes were cast in 640 precincts, whose sizes ranged

from 1637 (largest) to 132 (smallest), a difference

by a factor of more than 12. See Figure 2.

votes were cast in 640 precincts, whose sizes ranged

from 1637 (largest) to 132 (smallest), a difference

by a factor of more than 12. See Figure 2.

|

Let us assume a margin of victory of ![]() :

:

![]() .

Assume the adversary changes at most

.

Assume the adversary changes at most ![]() of a precinct's votes,

and assume a confidence level of

of a precinct's votes,

and assume a confidence level of ![]() (

(![]() ).

).

If the precincts were equal-sized, the Rule of

Thumb [16] would suggest auditing ![]() precincts.

The more accurate APR formula (3) suggests auditing 93

precincts (here

precincts.

The more accurate APR formula (3) suggests auditing 93

precincts (here ![]() precincts). The expected workload would

be 45852 votes counted. But the precincts are quite far from being

equal-sized. If we sample 93 precincts uniformly (using the APR recommendation

inappropriately here, since the precincts are variable-sized), we now

only achieve a 67% confidence of detecting at least one corrupted

precinct, when the adversary has changed enough votes to change the

election outcome. The reason is that all of the corruption can fit in

the 7 largest precincts now.

precincts). The expected workload would

be 45852 votes counted. But the precincts are quite far from being

equal-sized. If we sample 93 precincts uniformly (using the APR recommendation

inappropriately here, since the precincts are variable-sized), we now

only achieve a 67% confidence of detecting at least one corrupted

precinct, when the adversary has changed enough votes to change the

election outcome. The reason is that all of the corruption can fit in

the 7 largest precincts now.

The SAFE auditing method [11]

would determine that ![]() (reduced from

(reduced from ![]() for the uniform case,

since now the adversary need only corrupt the 7 largest precincts to change

the election outcome). Using a uniform sampling procedure to have at least

a 92% chance of picking one of those 7 precincts (or any corrupted precinct)

requires a sample size of 193 precincts (chosen uniformly), and an expected

workload of 95,155 votes to recount.

for the uniform case,

since now the adversary need only corrupt the 7 largest precincts to change

the election outcome). Using a uniform sampling procedure to have at least

a 92% chance of picking one of those 7 precincts (or any corrupted precinct)

requires a sample size of 193 precincts (chosen uniformly), and an expected

workload of 95,155 votes to recount.

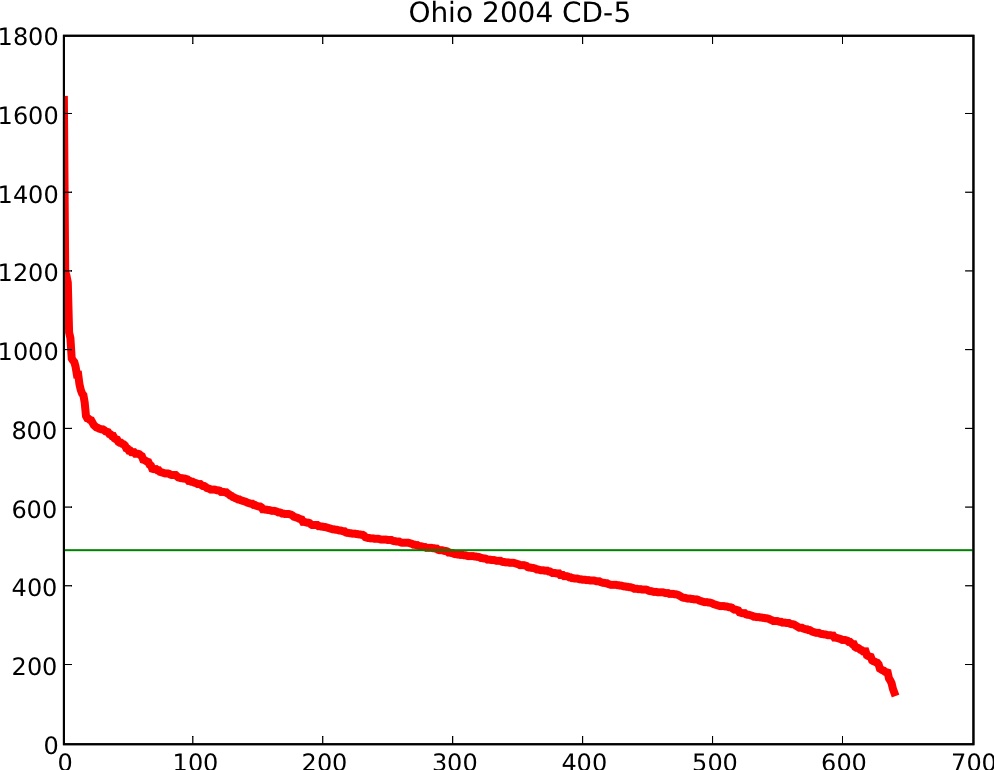

With the NEGEXP method, larger precincts are sampled

with greater probability. The adversary is thus prodded to disperse

his corruption more broadly, and thus needs to use more precincts,

which makes detecting the corruption easier for the auditor. The

NEGEXP method computes

![]() , and

audits a precinct of size

, and

audits a precinct of size ![]() with probability

with probability

![]() .

The largest precinct is audited with probability 0.408, while the

smallest is audited with probability 0.041.

The expected number of precincts selected for auditing is only 92.6, and

the expected workload is only 50,937 votes counted.

.

The largest precinct is audited with probability 0.408, while the

smallest is audited with probability 0.041.

The expected number of precincts selected for auditing is only 92.6, and

the expected workload is only 50,937 votes counted.

The PPEBWR method gave results almost identical to those for the NEGEXP method. The expected number of distinct precincts sampled was 91.6, and the expected workload was 50402 votes counted. Each precinct was sampled with a probability within 0.0031 of the corresponding probability for the NEGEXP method.

We see that for this example the NEGEXP method (or the PPEBWR method) is approximately twice as efficient (in terms of votes counted) as the SAFE method, for the same confidence level.

The program and datasets for our experiments are available at https://people.csail.mit.edu/rivest/pps/varsize.py, https://people.csail.mit.edu/rivest/pps/oh5votesonly.txt (Ohio).

The SAFE method may often be a poor choice when there are variable-precinct-sizes, particularly when there are a few very large precincts. One really needs a method that is tuned to variable-sized precincts by using variable auditing probabilities, rather than a method that uses uniform sampling probabilities.

The optimal auditing method can be represented as a

probability distribution assigning a probability ![]() to each

subset

to each

subset ![]() , where

, where ![]() indicates the probability that the

auditor will choose the subset of precincts,

indicates the probability that the

auditor will choose the subset of precincts, ![]() , for auditing. Since

there are

, for auditing. Since

there are ![]() such subsets, representing these probabilities

explicitly takes space exponential in

such subsets, representing these probabilities

explicitly takes space exponential in ![]() .

.

The optimal strategy can be found with linear programming, if the

number ![]() of precincts is not too large (say a dozen at most).

The linear programming formulation requires that

for each

subset

of precincts is not too large (say a dozen at most).

The linear programming formulation requires that

for each

subset ![]() of total error bound

of total error bound ![]() or more votes, the sum of the

probabilities of the subsets

or more votes, the sum of the

probabilities of the subsets ![]() having nonnegative intersection with

having nonnegative intersection with

![]() needs to be at least

needs to be at least ![]() .

.

![\begin{displaymath}

(\forall B)\left[

\left(\sum_{i\in B}e_i \ge M\right)

...

...t(\sum_{S:S\cap B \neq \phi}p_S \ge 1-\alpha\right)

\right]

\end{displaymath}](img168.png)

Finally, the objective function to be minimized is

the

expected number of votes to be recounted:

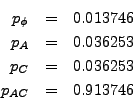

For example, suppose we have ![]() precincts

precincts ![]() with sizes

with sizes

![]() and error bounds

and error bounds

![]() ,

an adversarial corruption target

of

,

an adversarial corruption target

of ![]() votes, and a target significance level of

votes, and a target significance level of ![]() .

Then an optimal auditing strategy, when

the auditor is charged on a per-vote-recounted basis, is:

.

Then an optimal auditing strategy, when

the auditor is charged on a per-vote-recounted basis, is:

This approach is the ``gold standard'' for auditing with variable-sized precincts, in the sense that it definitely provides the most efficient procedure in terms of the stated optimization criterion. (We note that it is easy to refine this approach to handle the following variations: (1) an optimization criterion that is some linear combination of precincts counted and ballots counted and (2) a requirement that exactly (or at least, or at most) a certain number of precincts be audited.)

However, as noted, it may yield an auditing strategy with as many as

![]() potential actions (subsets to be audited) for the auditor, and so is not

efficient enough for real use, except for very small elections.

potential actions (subsets to be audited) for the auditor, and so is not

efficient enough for real use, except for very small elections.

We recommend the use of the PPEBWR method for use in an audit in a simple election. It gives the most efficient audit, for a given confidence level, of the audit methods studied here (other than the optimal method, which is too inefficient for practical use). Figure 3 summarizes the PPEBWR audit procedure recommended for use.

In an election containing multiple races (possibly with overlapping jurisdictions), the NEGEXP method is the more flexible. See Section 13.2 for discussion.

If the error bounds are computed using only the Linear Error Bound Assumption,

so that ![]() , then the probability of picking precinct

, then the probability of picking precinct ![]() is just

is just

![]() , so that we are picking with ``probability proportional to size''--this

is then the PPSWR procedure.

When the Linear Error Bound Assumption is used, one is assuming that

errors larger than

, so that we are picking with ``probability proportional to size''--this

is then the PPSWR procedure.

When the Linear Error Bound Assumption is used, one is assuming that

errors larger than ![]() in a precinct will be noticed and caught

``by other means''; one should ensure that this indeed happens.

(Letting runners-up pick precincts to audit could be such a mechanism.)

in a precinct will be noticed and caught

``by other means''; one should ensure that this indeed happens.

(Letting runners-up pick precincts to audit could be such a mechanism.)

Other considerations may result in interesting and reasonable modifications. Letting runners-up pick precincts to audit is probably helpful, although these precincts should then be ignored during the PPEBWR portion of the audit.

The ``escalation'' procedure for enlarging the audit when significant

discrepancies are found is (intentionally) left rather unspecified

here. We recommend reading Stark [19] for guidance. At one

extreme, one can perform a full recount of all votes cast. More

reasonably, one can utilize a staged procedure, where the error budget

![]() is allocated among the stages; only if enough new

discrepancies are discovered in one stage does auditing proceed to the

next.

is allocated among the stages; only if enough new

discrepancies are discovered in one stage does auditing proceed to the

next.

Figure 4 summarizes the NEGEXP audit procedure recommended for use. The NEGEXP method seems intrinsically more flexible than the PPEBWR method.

NEGEXP can handle multiple races with overlapping jurisdictions such that each precinct is audited at most once even when it is marked for auditing in multiple races. As with any basic auditing method, each precinct is audited independently with a precinct-specific probability. Assume that when a precinct is audited, we audit all races voted on in that precinct. Since the results for each race may imply a different auditing probability for the precinct, it suffices to audit the precinct with the maximum of the probabilities corresponding to the different races.

In a similar manner, the NEGEXP method can be used when the

auditing probabilities need to be changed (e.g. because of the effect

of late-reporting jurisdictions). Assume that the auditing probability

changes from ![]() to

to ![]() . If the precinct was audited in the first audit, nothing additional needs to be done.

If the precinct was not audited and

. If the precinct was audited in the first audit, nothing additional needs to be done.

If the precinct was not audited and ![]() , nothing needs to be done because we already audited the precinct

with a larger probability than we need to. Otherwise (when

, nothing needs to be done because we already audited the precinct

with a larger probability than we need to. Otherwise (when ![]() ), a dice-roll with probability

), a dice-roll with probability ![]() should be used to determine if the precinct should now be audited. The additional dice-roll ensures that the overall probability of auditing the precinct in discussion is

should be used to determine if the precinct should now be audited. The additional dice-roll ensures that the overall probability of auditing the precinct in discussion is ![]() , the final auditing probability.

, the final auditing probability.

It would be preferable in general, rather than having to deal with precincts of widely differing sizes, if one could somehow group the records for the larger precincts into ``bins'' for ``pseudo-precincts'' of some smaller standard size. (One can do this for say paper absentee ballots, by dividing the paper ballots into nominal standard precinct-sized batches before scanning them.) It is harder to do this if you have DRE's with wide disparities between the number of voters voting on each such machine. See Neff [12] and Wand [22] for further discussion.

We have presented two useful post-election auditing procedures: a powerful and flexible ``negative-exponential'' (NEGEXP) method, and a slightly more efficient ``sampling with probability proportional to size, with replacement'' (PPEBWR) method.

Thanks to Mark Lindeman for helpful discussions and the Ohio dataset. Thanks also to Kathy Dopp, Andy Drucker, Silvio Micali, Howard Stanislevic, Christos Papadimitriou, and Jerry Lobdill for constructive suggestions. Thanks to Phil Stark for his detailed feedback and pointers to the financial auditing literature.

This document was generated using the LaTeX2HTML translator Version 2002-2-1 (1.71)

Copyright © 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996,

Nikos Drakos,

Computer Based Learning Unit, University of Leeds.

Copyright © 1997, 1998, 1999,

Ross Moore,

Mathematics Department, Macquarie University, Sydney.

The command line arguments were:

latex2html -split 0 -show_section_numbers -local_icons -no_navigation varsize.tex

The translation was initiated by Raluca Ada Popa on 2008-06-30