|

Freenix 2000 USENIX Annual Technical Conference Paper

[Technical Index]

Webmin

A web-based system

administration tool for Unix

Abstract

This paper describes the design and

implementation of the Unix administration tool Webmin, available from

https://www.webmin.com/webmin/

. Webmin allows moderately experienced users to manage their Unix

system through a web browser interface, instead of editing

configuration files directly. The most recent version supports

Apache, Squid, BIND, Samba and many other servers and services. It

supports multiple operating systems and distributions, different

languages, multiple users each with different levels of access, and

SSL encryption.

The first part of the paper explains why

Webmin was developed and the initial design goals, and compares the

design to other similar tools such as Linuxconf. Subsequent sections

cover the design and implementation of the detailed multi-user

security model, the implementation of Webmin itself, how support for

multiple operating systems is handled and how internationalization

works. Finally, two Webmin modules are discussed in more detail and

various problems explained before the conclusion.

1 Introduction

For the

inexperienced user, Unix system administration can be daunting.

Almost all services have configuration files that must be edited

manually and often have complex formats. While these files are

usually well documented in man pages, it is often unclear

exactly how different sections and directives fit together.

Furthermore, a single misspelling or missing punctuation character

can ruin an entire configuration file.

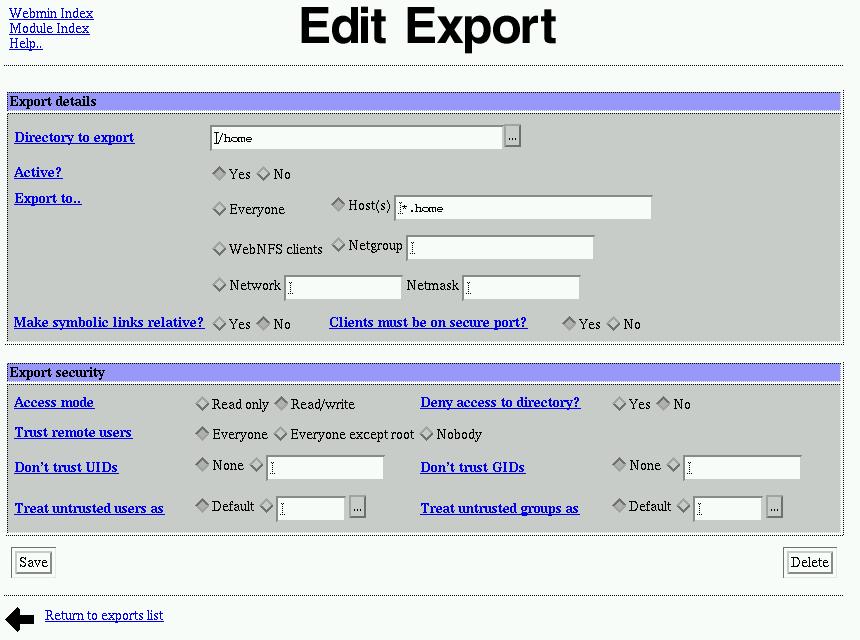

To make matters

worse, similar services have configuration files with different

structures and locations on different kinds of Unix systems. For

example, Solaris stores NFS exports in /etc/dfs/dfstab, while

Linux, FreeBSD and HPUX use /etc/exports - and all four use

different formats. For an inexperienced system administrator in

charge of several different types of systems, these inconsistencies

can make life difficult.

My aim in

writing a system administration tool was to solve both these

problems. It needed to provide a friendly user interface with basic

error checking, and consistency across the many different Unix

systems and distributions. Additional goals were completeness (all

reasonable options for the service being configured should be

settable) and non-destructiveness (comments and unknown options

should be unharmed).

This paper describes the design,

implementation and future of my system administration tool Webmin.

Section 2 explains the design of the system, section 3 the

implementation, section 4 covers two modules in detail, section 5

discusses problems encountered and finally section 6 concludes the

paper.

2 Design

2.1 System architecture

I decided early on that the easiest and

best administration user interface was one accessible through a web

browser. A web-based interface is platform independent, easy to

develop and accessible locally or over the network. I then began

writing CGI programs in perl to be run under an Apache webserver, but

eventually developed my own webserver written entirely in perl to

remove the dependency on Apache, which may not be available on users'

systems and dislikes running as root.

Perl was the natural choice of

implementation language for this project, as it has strong string

processing facilities for reading and updating configuration files,

and is available on every Unix platform that I might want my

administration tool to run on. Avoiding the need for compilation was

also an important goal, as some Unix variants do not even ship with a

compiler and there are many ways compilation can fail due to the lack

of a key library. With perl, all these problems have effectively been

already solved by the perl installation process.

While the web / perl / CGI architecture is

simple and easy to develop, it is not perfect. Because almost every

Webmin screen is generated by a CGI program, the web server must fork

a new process for each page, which can be slow on underpowered or

heavily loaded systems. This has been resolved in the most recent

versions by having the web server execute CGI programs in-process, in

a similar way to mod_perl. Response time can also be a problem when

managing distant servers, as every form submission must be processed

by the web server. The user interface capabilities of HTML are also

inferior to what is possible with a real user interface toolkit such

as Qt or Swing, although they can be improved somewhat through the

use of Javascript.

2.2 Alternative architectures and tools

I considered two other possible architectures before

deciding on the perl / CGI design :

A standard X11 application, written in C or

C++ and using Motif or Qt

This would have some advantages

from a user-interface point of view, as X applications have far more

controls and inputs available than web applications. However, C is

not a good language for writing string and file manipulation code in

and remote access would only be possible if the user was running an

X server. Because remote access was a major design goal, a

browser-based solution was preferable.

A Java applet client and server

This

option solves the remote access problem (because applets run in a

web browser), while still allowing complex user interfaces to be

developed. Unfortunately, at the time Webmin was designed Java

applets were still rather unreliable, especially large and complex

programs. In addition, Java's string manipulation capabilities are

not much better than C and far inferior to Perl.

When I started development in 1997, Webmin was not

the only administration tool for Unix system. Others available were :

Linuxconf

While today Linuxconf is a

very impressive tool with many of the same functions as Webmin, at

the time its development had only just begun. Its internal design is

different to Webmin in that instead of writing to config files

directly, it stores an internal list of changes, which is only

written out when the Activate Changes button is clicked. It

has a modular architecture like Webmin, though the modules are

shared libraries written in C++ rather than sets of CGI programs,

and it supports multiple languages for the user interface and help

screens.

Linuxconf's method of batching config file changes

has some advantages, such as the ability to have multiple related

changes applied simultaneously. The biggest disadvantage is the

possibility that changes made manually or by other tools could be

overwritten unexpectedly if Linuxconf's modifications have not been

applied for some time.

While it supports text, GTK and

browser-based user interfaces, most of the effort seems to have gone

into the GTK interface. This makes Linuxconf excellent for local

administration, but not as good for remote administration through a

web browser. Other problems are the lack of support for non-Linux

systems and the inability to handle multiple users with different

levels of permissions.

Redhat Control Panel

This is a

collection of small programs shipped with Redhat Linux for

configuring users, printers, networking and a few other services.

While it is good for those few services, it can only run as an X

application and only supports Redhat Linux config files.

SAM

This is a X/Motif administration

application shipped with the HP/UX operating system. Like the Redhat

control panel, it does not support remote access and only allows the

configuration of a few services such as NIS, users accounts and

networking.

2.3 Modules

Almost all of Webmin's functions are divided into

modules, each of which is a mostly independent set of CGI programs

responsible for managing some Unix feature or service. The programs

for each module are stored in a separate subdirectory below the base

Webmin directory (the webserver document root), and thus each module

is accessed by a URL like https://server:10000/module/

. Every module has some information associated with it, such as a

human-readable description, the operating systems it supports, and

the other modules that it depends upon.

When a user first logs in to the server, he will be

presented with a list of all the installed modules to which he has

access, with each module displayed as an icon from its directory.

Each module is displayed in one of five categories (Webmin, System,

Servers, Hardware and Others), with the module itself determining

which category it is in. This layout was adopted after the original

method of showing all modules on one page became too large and

cluttered.

The module system makes the distribution and addition

of new third-party modules simple. Third-party modules can be

distributed as Unix TAR files (normally with a .wbm

extension) for installation into existing Webmin servers. Because

each is fully self-contained, the installation process consists of

nothing more than untarring the module file and adding it to the

access list of the current user.

At the time of writing Webmin has 38 standard

modules, capable of configuring the Apache webserver, Unix users and

groups, Samba, Squid, Sendmail, NFS exports, disk partitions and

more. There are also 17 third-party modules for services such as

IPchains, Qmail, NetSaint and others.

2.4 User interface design

Because Webmin uses a web / CGI architecture, all

user interfaces are simply HTML pages and forms. The major goals in

designing the Webmin user interface were :

Consistency

I wanted all screens to

have a consistent look and feel, so that novice users could easily

find their way around. This meant using a standard color scheme,

title layout, footer and common interface elements, such as tables

of icons.

Simplicity

To make screens easy to use

(and to avoid the problem with large forms in some browsers), I

wanted to limit the amount of information and form inputs displayed

on each screen. To achieve this, many functions are broken down into

multiple screens although it would be possible to put all the

information on one page.

Compatibility

Because there are so

many web browser types and versions in use, I chose to use only the

lowest level of features possible. This meant no frames, DHTML,

Javascript or Java unless the there was no alternative (for example,

the File Manager feature is written in Java because it could not be

done any other way), or for adding non-vital features (such as the

optional file selection dialog in some screens).

2.5

Security

Because Webmin runs through a web server, the first

level of security is a standard HTTP login prompt displayed when the

user attempts to access the server. To prevent brute-force attacks,

Webmin can be configured to delay an increasing amount of time before

responding to each incorrect login. This will not defend against

sniffing the network for the password of a valid user, which is why

Webmin is also capable of running in SSL mode if the OpenSSL library

has been installed on the system it is running on.

A key feature of Webmin is support for multiple

users, each with different levels of access. The initial design only

supported granting each user either total access to a module, or no

access at all. This turned out to be inadequate however, as many

modules could be used in ways to gain root access and thus total

control of the system - for example, a Webmin user granted access to

all cron jobs could just create a job run as root and thus take over

the system.

The solution to this problem was the creation of an

additional more fine-grained level of security. This allowed the

granting to users only certain functions of each module, rather than

total control. For example, it is possible to give a Webmin user the

right to edit cron jobs only for selected Unix users, or the right

only to manage certain Apache virtual servers. This feature can be

very useful if a master administrator wants to delegate some tasks to

other admins, without giving them access to the entire system.

3 Implementation

3.1 Introduction

Webmin is implemented as a large number of perl CGI

programs, arranged into subdirectories called modules. Each module

handles the configuration of some Unix service, such as Apache, NFS

exports or cron. Each module has one or more libraries of common

functions, included by each CGI program with the require

command. Typically, these functions deal with the actual

configuration files, converting them to and from data structures used

by the actual programs. That way, there is a layer of abstraction

between most of the CGI programs and the system - although this

abstraction is not enforced, and is bypassed in some cases.

By abstracting the user

interface away from the actual configuration files, not only is much

repeated code avoided, but also the possibility is opened up for

modules to call each other. For example, the module fdisk

(Partitions on Local Disks) has a library fdisk-lib.pl that

contains functions for discovering the disks and partitions on Linux

systems. These functions are called by the raid (Linux RAID)

module to find disks available for inclusion into a RAID array, by

the lilo (Linux Bootup Configuration) module to display

bootable partitions, and by the mount (Disks and Filesystems)

module to display mountable partitions.

Webmin has its own

web server called miniserv that comes as part of the

distribution. Unlike a general-purpose webserver such as Apache, it

has very few features and only supports the retrieval of files and

the execution of CGI programs. Because it is written in Perl like the

rest of the Webmin programs, it has the ability to run CGIs

in-process without the need to fork and exec a new Perl

interpreter, in a similar manner to the mod_perl Apache

module. This provides a substantial speed increase on slow or low

memory systems.

3.2 Common functions

In addition to the

function library in each module, there is a file named web-lib.pl

in the top-level Webmin directory that contains functions used by all

modules. Every CGI program must require this library, either

directly or by via its module library. In addition, every CGI program

must call the function init_config

to read in the module configuration file, perform security checks and

set several global variables. Typically, this function is called by

the module's function library just after including web-lib.pl.

web-lib.pl

includes many different functions, which can be roughly broken down

into the following categories :

Standard user

interface functions for generating headers and footer, icon tables,

user and file dialogs and so on. These help provide a consistent

look across all Webmin screens.

File manipulation

functions for inserting, replacing and deleting lines in

configuration files.

Network functions,

for downloading files via FTP and HTTP.

Functions for making

'foreign' function calls. These are calls from CGI programs in one

module to functions in another module's library, done in such a way

that the called function has its environment set up just as if it

was being called by one of its own CGI programs.

Webmin-specific

functions for getting information about other modules, access

control, the Webmin version and so on.

Assorted convenience

functions, including CGI functions for reading form inputs into perl

variables.

3.3 Platform Independence

In order for Webmin to work on the many different

Unix variants and Linux distributions, it needs to know exactly which

operating system and version the user is running. This information is

determined at install time, either by asking the user or automatic

detection from the /etc/issue file or the output of uname.

Once the operating system is known, the appropriate configuration for

the OS is selected from each module and used to find and parse system

config files. Activate configuration files are stored in the

/etc/webmin directory, with

each module having its own subdirectory for its configuration file

and any other temporary files that it might create.

For example, the location of the Apache httpd.conf

file differs between every Linux distribution, and even between

different versions of the same distribution. Webmin can deal with

this though, as it knows where httpd.conf

is located on all the different operating systems and distributions

that it supports. Possible alternatives would be to ask the user

where every config files is (not very user friendly) or to find the

config files automatically by searching the entire filesystem (not

always possible, as many config files do not exist initially).

Because some operating

system behavior is too complex to encode in the simple Webmin config

files, some modules have separate Perl libraries for each OS. For

example, in the Disk Quotas module each OS library implements the

same set of functions, but in a different way to handle the different

ways quotas work on each operating system.

3.4 Internationalization

In order to support different languages, all the text

strings from most Webmin modules are no longer hard-coded into the

programs, but are instead stored in separate language files. Each

module has one file per supported language, the one to use being

selected by the user's current choice of language. When a program

needs to display some text or message, it uses a message code that is

looked up in the appropriate language file and converted to the

actual text is the correct language.

Because some words like Save,

Create and Default

are used by many modules, there is a master set of language files

that contain these messages for the use of all modules. These master

files also store messages used by the main Webmin menu and some

programs that are used by all modules.

The online help system also supports multiple

languages, with each help page stored in all the supported languages.

When a help page is requested, the file for the current language is

read and displayed. A similar selection process is also used for

displaying the module configuration page in the correct language.

With all translation in Webmin, if a message or page

is not available in the user's currently selected language then the

default language (currently English) will be used instead. This means

that partial translations can be contributed and are still useful,

and that the addition of new messages will not require the immediate

update of all language files.

3.5 Security Implementation

Because Webmin runs through a web server, the first

level of security is simply HTTP authentication enforced by the web

server using usernames and passwords from a standard Apache-style

users file. Because the server also enforces checks against

brute-force attacks and because the authentication protocol is

relatively simple, there is little chance of an attacker breaching

this level of security.

The second security level is enforced by module CGI

programs themselves, all of which check the HTTP username against the

list of allowed users for the module. This checking is done by the

common init_config function

which every program directly or indirectly calls. Because of this,

any program that does not check whether the current user is allowed

to access it could theoretically be a security hole. A better

alternative would be to have this level enforced by the webserver,

although that would complicate running Webmin under other webservers

such as Apache, as any change to the list of modules a user has

access to would require changing the Apache configuration as well.

The third security level

of fine-grained module access control is also enforced by the CGI

programs, but the complexity and variability of this access control

means that there is no common function that the programs can call.

Instead, each program checks a list of actions allowed by the current

user and displays an error message if the action the user requested

is unavailable. This means that the potential for accidentally

creating a security hole is much greater, but I see no other

alternative.

The Webmin webserver can also use the OpenSSL

and Net::SSLeay

libraries to encrypt communication between the server and browser

with SSL. Thanks to these libraries, the implementation of SSL is

relatively simple - the only difficulty is the provision of an SSL

certificate, which normally must be come from a trusted source like

Verisign, and associated with the hostname of the server. Because

Webmin's certificate is not valid, there is no defense against man in

the middle attacks that trick the user into thinking he is accessing

his Webmin server when he really is not.

4 Module Discussions

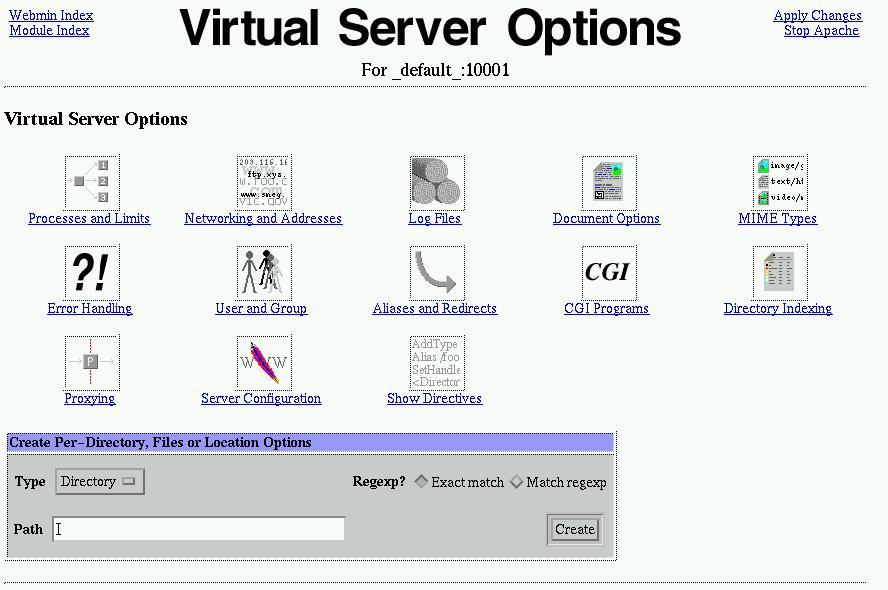

4.1 Apache Webserver

The Apache Webserver module is one of the most

complex, due to the massive number of configuration file directives

supported by Apache. My objective was to support all common Apache

versions, and as many different directives as possible. This was made

more complex by the large number of Apache modules, an unknown

combination of which could be compiled into each user's Apache

installation, and each of which could add several new directives.

Fortunately, it is possible to query an Apache

installation for version number, compiled in modules and dynamically

loaded modules. This information combined with the Webmin module's

built-in knowledge of the availability of each directive in each

Apache release makes it possible to edit the Apache config files

correctly. However, keeping up with the changes in each Apache

release can be difficult.

Once the supported

modules are known, a Perl library for each Apache module is read in,

each of which contains a function for editing and updating each

module directive. Each directive in each module is assigned a

category (such as Log Files

or Access Control), so

that when the user visits the Log Files submenu inputs

for all the directives in all modules related to that category are

displayed. This categorization system allows the large number

of directives to be broken down logically instead of all being

displayed on one huge page.

Because Apache supports subsections such as

<VirtualHost> or

<Directory>, the

user interface is further categorized to allow the editing of

directives in those sections, which are also broken down into

categories. This way even a large Apache configuration with many

virtual servers can be easy managed, and all supported directives can

be editing in all sections.

Because there are some

Apache directives (such as those in the mod_rewrite module)

that are too complex for Webmin to manage, the module also provides

support for manually editing parts of the config files. Comments and

unsupported directives such as these are not effected by the other

pages in the module.

4.2 Users and Groups

The Users and Groups module is designed to allowed

the creation, modification and deletion of Unix users and groups by

directly editing the /etc/passwd,

/etc/group and

/etc/shadow files.

This is complicated slightly by the difference in format and

existence of those files on different operating systems - for

example, some Linux distributions do not have an /etc/shadow

file at all, while some BSD-derived systems use the file

/etc/master.passwd as

their main source of user account information.

This functionality already

exists in many other administration tools however. What makes Webmin

unique in this area is the ability to update other parts of the

system when a user is created or modified. For example, you can

configure the Samba module to have a user added to Samba's encrypted

password file whenever a Unix user is added, something that normally

must be done manually. Similarly, the administrator can setup default

quotas to be assigned when new users are created.

5 Problems

After several years of development and use, I have

identified several design and implementation problems in Webmin :

Second and third level security

This

is still dependent on checking by individual CGI programs, and thus

security breaching are more likely than they should be. While the

second level is relatively secure and can be improved, there is no

easy way to improve the fine-grained third level of access control.

Only careful coding and close examination of the code by others can

help solve this problem.

Coding style

The development of Webmin

began when I was unfamiliar with Perl 5 features such as packages

and modules, and unfortunately the initial coding style has

continued through to this day. A good implementation would have made

each module a separate Perl module, allowing modules to call each

other using standard Perl syntax instead of the ugly foreign_

functions. The best long-term solution is to recode all the Webmin

modules as proper Perl modules, so that function calls between them

can be made with Perl's module::function

syntax.

Internationalization

Because

multi-language support was not part of the original design, several

older modules still have strings hard-coded into their programs.

Internationalization of these modules requires nothing more than

time and tedious work, as there is no reliable way this process

could be automated.

Keeping up with new releases

Because

new releases of servers such as Samba, Apache and Squid often have

new configuration directives or change the meanings of existing

ones, Webmin must keep up with the latest version of these programs.

In addition, new releases of operating systems and Linux

distributions which add new features and change the locations of

config files much also be kept track of. This is an unavoidable

task, but relatively easy if I download each new release of the

supported servers and install each new version of operating systems

and distributions to which Webmin has been ported. Fortunately,

programs such as VMware

make the testing of new PC-based operating systems relatively easy.

Documentation and help

Most modules

still lack online help, and there is no overall manual or

instructions on how to use Webmin. While most screens are relatively

self-explanatory to experienced system administrators, beginners

would benefit from a simple set of instructions on what DNS domains

are and how to set them up, how to create Unix accounts and so on.

6 Conclusion

From its initial releases that contained only a few

modules, Webmin has met its design goals and developed to support

many commonly used Unix services, becoming a useful and powerful

administration tool. This paper has covered the design and

implementation of Webmin, and should provide information for others

planning to develop similar tools or contribute to Webmin.

7 Availability

Webmin is distributed under a BSD-like license, and

thus is freely available. It can be downloaded from

https://www.webmin.com/webmin/

in .tar.gz , RPM and Solaris

package format. Several third-party modules contributed by others can

also be downloaded from the same URL.

|