2007 USENIX Annual Technical Conference

Pp. 171–184 of the Proceedings

Using Provenance to Aid in Personal File Search

Sam Shah⋆ Craig A. N. Soules † Gregory R. Ganger‡ Brian D. Noble⋆

⋆

University of Michigan †HP Labs ‡Carnegie Mellon University

As the scope of personal data grows, it becomes increasingly

difficult to find what we need when we need it. Desktop

search tools provide a potential answer, but most existing

tools are incomplete solutions: they index content, but

fail to capture dynamic relationships from the user’s

context. One emerging solution to this is context-enhanced

search, a technique that reorders and extends the results of

content-only search using contextual information. Within this

framework, we propose using strict causality, rather than

temporal locality, the current state of the art, to direct

contextual searches. Causality more accurately identifies data

flow between files, reducing the false-positives created by

context-switching and background noise. Further, unlike

previous work, we conduct an online user study with a

fully-functioning implementation to evaluate user-perceived

search quality directly. Search results generated by our

causality mechanism are rated a statistically-significant

17% higher on average over all queries than by using

content-only search or context-enhanced search with

temporal locality.

1 Introduction

Personal data has become increasingly hard to manage, find,

and retrieve as its scope has grown. As storage capacity

continues to increase, the number of files belonging to an

individual user, whether a home or corporate desktop user,

has increased accordingly [7]. The principle challenge is no

longer efficiently storing this data, but rather organizing it.

To reduce the friction users experience in finding their data,

many personal search tools have emerged. These tools build

a content index and allow keyword search across this

index. Despite their growing prevalence, most of these tools are,

however, incomplete solutions: they index content, not

context. They capture only static, syntactic relationships, not

dynamic, semantic ones. To see why this is important,

consider the difference between compiler optimization

and branch prediction. The compiler has access only to

the code, while the processor can see how that code is

commonly used. Just as run-time information leads to

significant performance optimizations, users find contextual

and semantic information useful in searching their own

repositories [22].

Context-enhanced search is beginning to receive attention,

but it is unclear what dynamic information is most useful in

assisting search. Soules and Ganger [21] developed a

system, named Connections, that uses temporal locality to

capture the provenance of data: for each new file written, the

set of files read “recently” form a kinship or relation

graph, which Connections uses to extend search results

generated by traditional static, content-based indexing

tools. Temporal locality is likely to capture many true

relationships, but may also capture spurious, coincidental

ones. For example, a user who listens to music while

authoring a document in her word processor may or may not

consider the two “related” when searching for a specific

document.

To capture the benefit of temporal locality while avoiding

its pitfall, we provide a different mechanism to deduce

provenance: causality. That is, we use data flow through and

between applications to impart a more accurate relation

graph. We show that this yields more desirable search results

than either content-only indexing or kinship induced by

temporal locality.

Our context-enhancing search has been implemented

for Windows platforms. As part of our evaluation, we

conduct a user study with this prototype implementation

to measure a user’s perceived search quality directly.

To accomplish this, we adapt two common techniques

from the social sciences and human-computer interaction

to the area of personal file search. First, we conduct

a randomized, controlled trial to gauge the end-to-end

effects of our indexing technique. Second, we conduct

a repeated measures experiment, where users evaluate the

different indexing techniques side-by-side, locally on their

own machines. This style of experiment is methodogically

superior as it measures quality directly while preserving

privacy of user data and actions.

The results indicate that our causal provenance algorithm

fares better than using temporal locality or pure content-only

search, being rated a statistically-significant 17% higher, on

average, than the other algorithms by users with minimal

space and time overheads. Further, as part of our study,

we also provide some statistics about personal search

behavior.

The contributions of this paper are:

- The identification of causality as a useful

mechanism to inform contextual indexing tools and

a description of a prototype system for capturing it.

- An exploration of the search behavior of a

population of 27 users over a period of one month.

- A user study, including a methodology for

evaluating personal search systems, demonstrating

that causality-enhanced indexing provides higher

quality search results than either those based on

temporal locality or those using content information

only.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2, we give an overview of related work. Section 3

describes how our system deduces and uses kinship

relationships, with Section 4 outlining our prototype

implementation. Section 5 motivates and presents our

evaluation and user study and Section 6 explores the search

behavior of our sample population. Finally, Section 7

concludes.

2 Related Work

There are various static indexing tools for one’s filespace.

Instead of strict hierarchal naming, the semantic file

system [10] allows assignment of attributes to files,

facilitating search over these attributes. Since most users are

averse to ascribing keywords to their files, the semantic

file system provides transducers to distill file contents

into keywords. The semantic file system focuses on the

mechanism to store attributes, not on content analysis to

distill these attributes.

There are several content-based search tools available

today, including Google Desktop Search, Windows Desktop

Search and Yahoo! Desktop Search, among others.

These systems extract a file’s content into an index, permitting search across this index. While the details of

such systems are opaque, it is likely they use forefront

technologies from the information retrieval community.

Several such advanced research systems exist, Indri [1]

being a prime example. These tools are orthogonal to our

system in that they all analyze static data with well-defined

types to generate an index, ignoring crucial contextual

information that establishes semantic relationships between

files.

The seminal work in using gathered context to aid in file

search is by Soules and Ganger [21] in the form of a file

system search tool named Connections. Connections

identifies temporal relationships between files and uses that

information to expand and reorder traditional content-only

search results, improving average precision and recall

compared to Indri. We use some component algorithms from

Connections (§3.2) and compare against its temporal locality

approach (§3.1.1).

Our notion of provenance is a subset of that used by the

provenance-aware storage system (PASS) [17]. PASS

attempts to capture a complete lineage of a file, including the

system environment and user- and application-specified

annotations of provenance. A PASS filesystem, if available,

would negate the need for our relation graph. Indeed, the

technique used by PASS to capture system-level provenance

is very similar to our causality algorithm (§3.1.2).

Several systems leverage other forms of context for file

organization and search. Phlat [5] is a user interface for

personal search, running on Windows Desktop Search, that

also provides a mechanism for tagging or classifying

of data. The user can search and filter by contextual

cues such as date and person. Our system provides a

simpler UI, permitting search by keywords only (§4), but

could use Phlat’s interface in the future. Another system,

called “Stuff I’ve Seen” [8], remembers previously seen

information, providing an interface that allows a user to

search their historical information using contextual cues.

The Haystack project [12] is a personal information

manager that organizes data, and operations on data, in a

context-sensitive manner. Lifestreams [9] provides an

interface that uses time as its indexing and presentation

mechanism, essentially ordering results by last access time.

Our provenance techniques could enhance these systems

through automated clustering of semantically-related

items.

3 Architecture

Our architecture matches that of Soules and Ganger [21]: we

augment traditional content search using kinship relations

between files. After the user enters keywords in our search

tool, the tool runs traditional content-only search using those

keywords—the content-only phase—and then uses the

previously constructed relation graph to reorder these results

and identify additional hits—the context-enhancing

phase. These new results are then returned to the user.

Background tasks run on the user’s machine to periodically

index a file’s content for the content-only phase and to

monitor system events to build the relation graph for the

context-enhancing phase. This section describes how the

system deduces and uses these relationships to re-rank

results.

3.1 Inferring Kinship Relationships

A kinship relation, f → f ′ where f and f ′ are files on a

user’s system, indicates that f is an ancestor of f ′, implying

that f may have played a role in the origin of f ′. These

relationships are encoded in the relation graph, which is used

to reorder and extend search results in the context-enhancing

phase.

We evaluate two methods of deducing these kinship

relations: temporal locality and causality. Both methods

classify the source file of a read as input and the destination

file of a write as output by inferring user task behavior from

observed actions.

3.1.1 Temporal Locality Algorithm

The temporal locality algorithm, as employed in

Soules and Ganger [21], infers relations by maintaining a

sliding relation window of files accessed within the previous

t seconds system-wide. Any write operation within this

window is tied to any previous read operation within the

window. This is known as the read/write operational filter

with directed links in Soules and Ganger [21], which was

found the most effective of several considered.

Consider the sequence of system events shown in

Figure 1. There are three processes, A, B, and C, running

concurrently. C reads files u and v, A reads files x and y. B

reads w and copies data to A through a clipboard IPC action

initiated by the user. Following this, A then writes file

z.

The relation window at z’s write contains reads of y, w,

and v. The temporal locality algorithm is process agnostic

and views reads and writes system-wide, distinguishing only

between users. The algorithm thus returns the relations

{y → z,w → z,v → z}.

The relation window attempts to capture the transient

nature of a user task. Too long a window will cause unrelated

tasks to be grouped, but too short a window will cause

relationships to be missed.

3.1.2 Causality Algorithm

Rather than using a sliding window to deduce user tasks, this

paper proposes viewing each process as a filter that mutates

its input to produce some output. This causality algorithm

tracks how input flows—at the granularity of processes—to

construct kinship relations, determining what output is

causally related to which inputs.

Specifically, whenever a write event occurs, the following

relations are formed:

(a) Any previous files read within the same process are

tied to the current file being written;

(b) Further, the algorithm tracks IPC transmits and

its corresponding receives, forming additional

relationships by assessing the transitive closure

of file system events formed across these IPC

boundaries. That is, for each relation f → f ′, there is a directed left-to-right

path in the time diagram starting at a read event of file f and

ending at the write of file f ′. There is no temporal bound

within this algorithm.

Reconsidering Figure 1, A reads x and y to generate z; the

causality algorithm produces the relations {x → z,y → z}

via condition (a). B produces no output files given its read

of w, but the copy-and-paste operation represents an IPC

transmit from B with a corresponding receive in A. By

condition (b), this causes the relation w → z to be made.

C’s reads are dismissed as they do not influence the write of

z or any other data.

Causality forms fewer relationships than temporal locality,

avoiding many false relationships. Unrelated tasks happening

concurrently are more likely to be deemed related under

temporal locality, while causality is more conservative. Further, when a user switches between disparate tasks,

the temporary period where incorrect relations form

under temporal locality is mitigated by the causality

algorithm.

A user working on a spreadsheet with her music player in

the background may form spurious relationships between her

music files and her document under temporal locality, but not

under causality; those tasks are distinct processes and no

data is shared. Additionally, if she switches to her email

client and saves an attachment, her spreadsheet may be

an ancestor of that attachment under temporal locality

if the file system events coincide within the relation

window.

Long-lived processes are a mixed bag. A user opening a

document in a word processor, writing for the afternoon, then

saving it under a new name would lose the association with

the original document under temporal locality, but not

causality. A user working with her text editor to author

several unrelated documents within the same process would

have spurious relations formed with causality, but perhaps

not with temporal locality.

Causality can fare worse under situations where data

transfer occurs through hidden channels due to loss of real

context. This is most evident when a user exercises her

brain as the “clipboard,” such as when she reads a value

off a spreadsheet and then keys it manually into her

document. As future work, we are investigating using

window focus to demarcate user tasks [18] as a means to

group related processes together and capture these hidden

channels.

3.1.3 Relation Graph

Relations formed are encoded in the relation graph: a

directed graph whose vertices represent files on a user’s

system with edges constituting a kinship relation between

files and the weight of that edge representing the strength of

the bond. The edge’s direction represents an input file to an

output file.

For each relation of the form f → f ′, the relation graph

consists of an edge from vertex f to vertex f ′ with the edge

weight equalling the count of f → f ′ relations seen. To

prevent heavy weightings due to consecutive writes to a

single file, successive write events are coalesced into a single

event in both algorithms.

3.2 Reranking and Extending Results

After a query is issued, the tool first runs traditional

content-only search using keywords given by the user, then

uses the relation graph to reorder results and identify

additional hits. This basic architecture is identical to that of

Soules and Ganger [21].

Each content-only result is assigned its relevance score as

its initial rank value. The relation graph is then traversed

breadth-first for each content-only result. The path length, P ,

is the maximum number of steps taken from any starting

node in the graph during this traversal. Limiting the number

of steps is necessary to avoid inclusion of weak, distant

relationships and to allow our algorithm to complete in a

reasonable amount of time.

Further, because incorrect lightly-weighted edges may

form, an edge’s weight must provide some minimum

support: it must make up a minimum fraction of the source’s

outgoing weight or the sink’s incoming weight. Edges below

this weight cutoff are pruned.

The tool runs the following algorithm, called basic BFS,

for P iterations. Let Em be the set of all incoming edges to

node m, with enm ∈ Em being a given edge from n to m

and γ(enm) being the fraction of the outgoing edge weight

for that edge. wn0 is the initial value, its content-only score,

of node n. α dictates how much trust is placed in each

specific weighting of an edge. At the i-th iteration of the

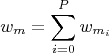

algorithm:

![∑ [ ]

wmi = wni-1 ⋅ γ(enm)⋅α + (1- α)

enm ∈Em](images/usenix071x.png) | (1a) |

After all P runs of the algorithm, the total weight of each

node is:

| (1b) |

In (1a), heavily-weighted relationships and nodes with

multiple paths push more of their weight to node m. This

matches user activity as files frequently used together will

receive a higher rank; infrequently seen sequences will

receive a lower rank. The final result list sorts by (1b) from

highest to lowest value.

As an example, consider a search for “project budget

requirements” that yields a content-only phase result of

budget.xls with weight wa0 = 1.0. Assume that during the

context-enhancing phase, with parameters P=3, α=0.75 and

no weight cutoff, the relation graph shown in Figure 2 is

loaded from disk. Take node expenserep.doc, abbreviated as

d. The node’s initial weight is wd0 = 0 as it is absent from

the content-only phase results. The algorithm proceeds as

follows for P iterations:

| wd1 | = wa0 ⋅ γ(ead) ⋅ α + (1 - α) γ(ead) ⋅ α + (1 - α)![]](images/usenix075x.png) | | by (1a) | | | |

| | = 1.0 ⋅ (7∕10) ⋅ 0.75 + 0.25 (7∕10) ⋅ 0.75 + 0.25![]](images/usenix077x.png) = 0.775 = 0.775 | | | |

| | wd2 | = 0 | | as wa1=0 | | | |

| | wd3 | = 0 | | as wa2=0 | | | |

| | Finally, the total weight of node d is: | |

| | wd | = 0 + 0.775 + 0 + 0 = 0.775 | | by (1b) | | | | |

The final ordered result list, with terminal weights in

parentheses, is: budget.xls (1.0), expenserep.doc (0.775),

memo1.doc (0.475) and memo2.doc (0.475). In this

example, both memo files have identical terminal weights;

ties are broken arbitrarily.

Though straightforward, this breadth-first reordering and

extension mechanism proves effective [21]. We are also

investigating using machine learning techniques for more

accurately inferring semantic order.

4 Implementation Our implementation runs on Windows NT-based systems.

We use a binary rewriting technique [11] to trace all file

system and interprocess communication calls. We chose such

a user space solution as it allows tracking high-level calls in

the Win32 API.

-

File System Operations

- Opening and closing files (e.g.,

CreateFile, __lopen, __lcreat, CloseHandle); reading

and writing files (e.g., ReadFile,

WriteFile, ReadFileEx, . . . ); moving, copying, and

unlinking files (e.g., MoveFile, CopyFile, DeleteFile,

. . . ).

-

IPC Operations

- Clipboard (DDE), mailslots, named

pipes.

-

Other

- Process creation and destruction: CreateProcess,

ExitProcess.

-

Not interposed

- Sockets, data

copy (i.e., WM_COPYDATA messages), file mapping

(a.k.a. shared memory), Microsoft RPC, COM.

|

| Table 1: | System calls which our tool interposes on. We

trace both the ANSI and Unicode versions of these calls. |

|

When a user first logs in, our implementation instruments

all running processes, interposing on our candidate set

of system calls as listed in Table 1. It also hooks the

CreateProcess call, which will instrument any subsequently

launched executables. Care was required to not falsely trip

anti-spyware tools. Each instrumented process reports its

system call behavior to our background collection daemon,

which uses idle CPU seconds, via the mailslots IPC

mechanism. For performance reasons, each process

amortizes 32K or 30 seconds worth of events across a single

message. The collection daemon contemporaneously creates

two relation graphs: one using temporal locality (§3.1.1) and

one using causality (§3.1.2).

If a file is deleted, its node in the relation graph becomes a

zombie: it relinquishes its name but maintains its current

weight. The basic BFS algorithm uses a zombie’s weight in

its calculations, but a zombie can never be returned in the

search result list. We currently do not prune zombies from

the relation graph.

Content indexing is done using Google Desktop Search

(GDS) with its exposed API. We expect GDS to use

state-of-the-art information retrieval techniques to conduct

its searches. We chose GDS over other content indexing

tools, such as Indri [1], because of its support for more file

types. All queries enter through our interface: only GDS’s

indexing component remains active, its search interface is

turned off. GDS also indexes email and web pages, but we

prune these from the result set. In the future, we intend to

examine email and web work habits and metadata to further

enhance search.

A complication arises, however. GDS allows sorting by

relevance, but it does not expose the actual relevance scores.

These are necessary as they form the initial values of the

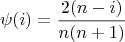

basic BFS algorithm (§3.2). We use:

| (2) |

to seed the initial values of the algorithm. Here, n is the total

number of results for a query, and i is the result’s position in

the result list. Equation (2) is a strict linear progression with relevance values constrained such that the sum of the values

is unity, roughly matching the results one would expect from

a TF/IDF-type system [3]. Soules [20] found that equation

(2)performs nearly as well as real relevance scores: (2)

produces a 10% improvement across all recall levels in

Soules’s study, while real relevance scores produce a 15%

improvement.

Users interact with our search system through an icon in

the system tray. When conducting a search, a frame, shown

in Figure 3, appears, allowing the user to specify her query

keywords in a small text box. Search results in batches of ten

appear in the upper part of the frame. A snippet of each

search result, if available, is presented, along with options to

preview the item before opening. Previewing is supported by

accessing that file type’s ActiveX control, as is done in web

browsers.

In most desktop search applications, ours included, the

search system is available to users immediately after

installation. Because the content indexer works during idle

time and little to no activity state has been captured to build

our relation graph when first installed, search results during

this initial indexing period are usually quite hapless. We

warn users that during this initial indexing period that their

search results are incomplete.

Our implementation uses a relation window of 30 seconds

and basic BFS with a weight cutoff of 0.1% and parameters

P = 3 and α = 0.75. These parameters were validated by

Soules and Ganger [21].

To prevent excessively long search times, we restrict

the context-enhancing phase to 5 seconds and return

intermediate results from basic BFS. Although, as shown in

our evaluation (§5.3.3), we rarely hit this limit. Due to our

unoptimized implementation, we expect a commercial

implementation to perform slightly better than our results

would suggest.

5 User Study/Evaluation

Our evaluation has four parts: first, we explain the

importance of conducting a user study as our primary

method of evaluation. Second, we describe a controlled trial

coupled with a rating task to assess user satisfaction. The

results indicate that our causality algorithm is indeed an

improvement over content-only indexing, while temporal

locality is statistically indistinguishable. Third, we evaluate

the time and space overheads of our causality algorithm,

finding that both are reasonable. Fourth, we dissect user

elicited feedback of our tool.

5.1 Experimental Approach

Traditional search tools use a corpus of data where queries

are generated and oracle result sets are constructed by

experts [3]. Two metrics, precision (minimizing false

positives) and recall (minimizing false negatives) are then

applied against this oracle set for evaluation. Personal file search systems, however, are extremely

difficult to study in the laboratory for a variety of reasons.

First, as these systems exercise a user’s own content, there is

only one oracle: that particular user. All aspects of the

experiment, including query generation and result set

evaluation, must be completed by the user with their

own files. Second, a user’s search history and corpus is

private. Since the experimenter lacks knowledge of each

user’s data, it’s nearly impossible to create a generic set

of tasks that each user could perform. Third, studying

context-enhanced search is further complicated by the

need to capture a user’s activity state for a significant

length of time, usually a month or more, to develop

our dynamic indices—an impractical feat for an in-lab

experiment.

In lieu of these difficulties with in-lab evaluation,

Soules and Ganger [21] constructed a corpus of data

by tracing six users for a period of six months. At the

conclusion of their study, participants were asked to submit

queries and to form an oracle set of results for those queries.

Since each user must act as an oracle for their system, they

are loathe to examine every file on their machine to build this

oracle. Instead, results from different search techniques were

combined to build a good set of candidates, a technique

known as pooling [3]. Each search system can then be

compared against each oracle set using precision and

recall.

While an excellent initial evaluation, such a scheme may

exhibit observational bias: users will likely alter their

behavior knowing their work habits are being recorded. For

instance, a user may be less inclined to use her system as she

normally would for she may wish to conceal the presence of

some files. It is quite tough to find users who would be

willing to compromise their privacy by sharing their activity

and query history in such a manner.

Further, to generate an oracle set using pooling, we need a

means to navigate the result space beyond that returned from

content-only search. That is, we need to use results from

contextual indexing tools to generate the additional pooled

results. However, the lack of availability of alternative

contextual indexing tools means that pooling may be biased

toward the contextual search tool under evaluation, as

that tool is the only one generating the extra pooled

results.

We also care to evaluate the utility of our tool beyond the

metrics of precision and recall. Precision and recall fail to

gauge the differences in orderings between sets of results.

That is, two identical sets of results presented in different

order will likely be qualitatively very different. Further, while

large gains in mean average precision are detectable to the

user, nominal improvements remain inconclusive [2]. We

would like a more robust measurement that evaluates a user’s

perception of search quality.

For these reasons, we conduct a user study and deploy an

actual tool participants can use. First, we run a pre-post

measures randomized controlled trial to ascertain if users

perceive end-to-end differences between content-only search

and our causality algorithm with basic BFS. Second, we

conduct a repeated measures experiment to qualitatively

measure search quality: we ask users to rate search orderings

of their previously executed queries constructed by

content-only search and of results from our different

dynamic techniques.

5.1.1 Background

We present a terse primer here on the two techniques we

use in our user study. For more information on these

methods, the interested reader should consult Bernard [4] or

Krathwohl [14].

A pre-post measures randomized controlled trial is a study

in which individuals are allocated at random to receive one

of several interventions. One of these interventions is the

standard of comparison, known as the “control,”

the other interventions are referred to as “treatments.”

Measurements are taken at the beginning of the study, the

pre-measure, and at the end, the post-measure. Any change

between the treatments, accounting for the control, can be

inferred as a product of the treatment. In this setup,

the control group handles threats to validity; that any

exhibited change is caused by some other event than the

treatment. For instance, administering a treatment can

produce a psychological effect in the subject where the act

of participation in the study results in the illusion that

the treatment is better. This is known as the placebo

effect.

Consider that we have a new CPU scheduling algorithm

that makes interactive applications feel more responsive

and we wish to gauge any user-perceived difference in

performance against the standard scheduler. To accomplish

this, we segment our population randomly into two groups,

one which uses the standard scheduler, the control group, and

the other receives our improved scheduler, the treatment

group. Neither group knows which one they belong to. At the

beginning of the study, the pre-measure, we ask users to

estimate the responsiveness of their applications with a

questionnaire. It’s traditional to use a Likert scale in which

respondents specify their level of agreement to a given

statement. The number of points on an n-point Likert

scale corresponds to an integer level of measurement,

where 1 to n represents the lowest to highest rating. At

the end of the study, the post-measure, we repeat the

same questionnaire. If the pre- and post-measures in

the treatment group are statistically different than the

pre- and post-measures in the control group, we can

conclude our new scheduler algorithm is rated better by users.

Sometimes it is necessary or useful to take more than one

observation on a subject, either over time or over many

treatments if the treatments can be applied independently.

This is known as a repeated measures experiment. In our

scheduler example, we may wish to first survey our subject,

randomly select an algorithm to use and have the subject run

the algorithm for some time period. We can then survey our

subject again and repeat. In this case, we have more than one

observation on a subject, with each subject acting as its own

control.

Traditionally, one uses ANOVA to test the statistical

significance of hypotheses among two or more means

without increasing the α (false positive) error rate that occurs

with using multiple t-tests. With repeated measures data, care

is required as the residuals aren’t uniform across the

subjects: some subjects will show more variation on some

measurements than on others. Since we generally regard the

subjects in the study as a random sample from the population

at large and we wish to model the variation induced

in the response by these different subjects, we make

the subjects a random effect. An ANOVA model with

both fixed and random effects is called a mixed-effects

model [19].

5.1.2 Randomized Controlled Trial

In our study, we randomly segment the population into a

control group, whose searches return content-only results,

and a treatment group, whose searches return results

reordered and extended by basic BFS using a relation graph

made with the causality algorithm.

To reduce observational bias and protect privacy, our

tool doesn’t track a user’s history, corpus, or queries,

instead reporting aggregate data only. During recruitment,

upon installation, and when performing queries, we

specifically state to users that no personal data is shared

during our experiment. We hope this frees participants to

use their machines normally and issue queries without

hindrance.

The interface of both systems is identical. To prevent

the inefficiency of our unoptimized context-enhancing

implementation from unduly influencing the treatment group,

both groups run our extended search, but the control group

throws away those results and uses content-only results

exclusively.

The experiment is double-blind: neither the participants

nor the researchers knew who belonged to which group. This

was necessary to minimize the observer-expectancy effect;

that unconscious bias on the part of the researchers may

appear during any potential support queries, questions, or

follow ups. The blinding process was computer controlled.

Evaluation is based on pre- and post-measure questionnaires

where participants are asked to report on their behavior using

5-point Likert scale questions. For example, “When I need to

find a file, it is easy for me to do so quickly.” Differences in

the pre- and post-measures against the control group

indicate the overall effect our causality algorithm has

in helping users find their files. We also ask several

additional questions during the pre-survey portion to

understand the demographics of our population and

during the post-survey to elicit user feedback on our

tool.

We pre-test each survey instrument on a small sample of a

half-dozen potential users who are then excluded from

participating in our study. We encourage each pre-tester

to ask questions and utilize “think-alouds,” where the

participant narrates her thought process as she’s taking the

survey. Pre-testing is extremely crucial as it weeds out poorly

worded, ambiguous, or overly technical elements from

surveys. For example, the first iteration of our survey

contained the question, “I often spend a non-trivial amount

of time looking for a file on my computer.” Here, the word

“non-trivial” is not only equivocal, it is confusing. A more

understandable question would be to set an exact time span:

“I often spend 2 minutes or more a day looking for a file on

my computer.”

We also conducted a pilot study with a small purposive

sample of colleagues who have trouble finding their files.

This allowed us to vet our tool and receive feedback on our

study design. Naturally, we exclude these individuals and

this data from our overall study.

5.1.3 Rating Task

We wish to evaluate the n different dynamic algorithms

against each other. Segmenting the study population into n

randomized groups can make finding and managing a large

enough sample difficult. More importantly, as we will show,

controlled experiments on broad measurements for personal

search behavior are statistically indistinguishable between

groups; we believe users have difficultly judging subtle

differences in search systems.

To that end, we also perform a repeated measures

experiment. As we can safely run each algorithm

independently, we contemporaneously construct relation graphs

using both the temporal locality and causality algorithms in

both groups. At the conclusion of the study, we choose up to

k queries at random that were previously successfully

executed by the user and re-execute them. Different views, in

random order, showing each different algorithm’s results are

presented; the user rates each of them independently

using a 5-point Likert scale. We use these ratings to

determine user-perceived differences in each search algorithm.

We define “successfully executed” to be queries where the

user selected at least one result after execution. To prevent

users from rating identical, singular result lists—which

would give us no information—we further limit the list of

successful queries by only considering queries where at least

one pair of algorithms differs in their orderings. With this

additional constraint, we exclude an additional 2 queries

from being rated.

The rating task occurs at the end of the study and not

immediately after a query as we eschew increasing the

cognitive burden users experience when searching. If

users knew they had to perform a task after each search,

they might avoid searches because they anticipate that

additional task. Worse, they might perfunctorily complete

the task if they are busy. In a longer study, it would be

beneficial to perform this rating task at periodic intervals to

prevent a disconnect with the query’s previous intent in the

user’s mind. Previous work has shown a precipitous drop

in a user’s ability to recall computing events after one

month [6].

Finally, we re-execute each query rather than present

results using algorithm state from when the query was first

executed. The user’s contextual state will likely be disparate

between when the query was executed and at the time of the

experiment; any previous results could be invalid and may

potentially cause confusion.

In our experiment, we chose k=7 queries to be rated by

the user. We anecdotally found this to provide a reasonable

number of data points without incurring user fatigue. Four

algorithms were evaluated: content-only, causality, temporal

locality and a “random-ranking” algorithm, which consists

of randomizing the top 20 results of the content-only

method.

5.2 Experimental Results

Our study ran during June and July 2006, starting with

75 participants, all undergraduate or graduate students at the

University of Michigan, recruited from non-computer

science fields. Each participant was required to run our

software for at least 30 days, a period allowing a reasonable

amount of activity to be observed while still maintaining a

low participant attrition rate. Of the initial 75 participants,

27 (36%), consisting of 15 men and 12 women, completed

the full study. This is more than four times the number of

Soules and Ganger [21]. Those who successfully completed

the study received modest compensation.

To prevent cheating, our system tracks its installation,

regularly reporting if it’s operational. We are confident that

we identify users who attempt to run our tool for shorter than

the requisite 30 days. Further, to prevent users from

creating multiple identities, participants must supply their

institutional identification number to be compensated. In

all, we excluded 4 users from the initial 75 because of

cheating.

5.2.1 Randomized Controlled Trial

Evaluating end-to-end effects, as in our controlled trial,

yields inconclusive results. Figure 4 shows box-and-whisker

plots of 5-point Likert ratings for key survey questions

delineated by control and treatment group. For those

unfamiliar: on a box-and-whiskers plot, the median for each

dataset is indicated by the center dot, the first and third

quartiles, the 25th and 75th percentiles respectively—the

middle of the data—are represented by the box. The lines

extending from the box, known as the whisker, represent 1.5

times this interquartile range and any points beyond the

whisker represent outliers. The box-and-whiskers plot is a

convenient method to show not only the location of

responses, but also their variability.

Figure 4(a) is the pre- and post-measures difference on a

Likert rating on search behavior: “When I need to find a

file, it is easy for me to do so quickly.” Sub figures (b)

and (c) are post-survey questions on if the tool would

change their behavior in organizing their files (i.e., “I

would likely put less effort in organizing my files if I

had this tool available”) or whether this tool should be

bundled as part of every machine (i.e., “this tool should

be essential for any computer”). With all measures,

the results are statistically insignificant between the

control and treatment groups (t25 = -0.2876,p=0.776;

t25 = 0.0123,p=0.9903; t25 = -0.4995,p=0.621,

respectively).

We also consider search behavior between the groups.

Figure 5 shows the rank of the file selected after performing

a query. Those in the treatment group select items higher in

the list than those in the control group, although not

significantly (t51 = 1.759;p=0.0850).

We divide query execution into sessions, each session

representing a series of semantically related queries.

Following Cutrell et al. [5], we define a session to comprise

queries that have an inter-arrival rate of less than 5 minutes.

The session length is the number of queries in a session, or,

alternatively, the query retry rate. As Figure 6 shows, the

treatment group has a shorter average session length

(t97 = 2.136,p=0.042), with geometric mean session lengths

of 1.30 versus 1.66 queries per session, respectively. 13.5%

and 19.0% of sessions in the control and treatment groups,

respectively, ended with a user opening or previewing an

item.

This data is, however, inconclusive. While at first blush it

may appear that with the causality algorithm users are

selecting higher ranked items and performing fewer queries

for the same informational need, it could be just as well

that users give up earlier. That is, perhaps users fail to

select lower ranked items in the treatment group because

those items are irrelevant. Perhaps users in the treatment

group fail to find what they’re looking for and cease

retrying, leading to a shorter session length. In hindsight, it

would have been beneficial to ask users if their query was

successful when the search window was closed. If we had

such data available, we could ascertain whether shorter

session lengths and opening higher ranked items were

a product of finding your data faster or of giving up

faster.

The lack of statistically significant end-to-end effects

stems from the relatively low sample size coupled with the

heterogeneity of our participants. To achieve statistical

significance, our study would require over 300 participants to

afford the standard type II error of β = 0.2 (power t-test,

Δ = 0.2,σ = 0.877,α = 0.05). Attaining such a high

level of replication is prohibitively expensive given our

resources. Instead, our evaluation focuses on our rating

task.

5.2.2 Rating Task

The rating task yielded more conclusive results. 16 out

of our 27 participants rated an aggregate total of 34

queries, an average of 2.13 queries per subject (σ=1.63).

These 34 rated queries likely represent a better candidate

selection of queries due to our “successfully executed”

precondition (§5.1.3): we only ask users to rate queries

where they selected at least one item from the result set for

that search. 11 participants failed to rate any queries: 3 users

failed to issue any, the remaining 8 failed to select at least

one item from one of their searches.

Those remaining 8 issued an average of 1.41 queries

(σ=2.48), well below the sample average of 6.74 queries

(σ=6.91). These likely represent failed searches, but it is

possible that users employ search results in other ways. For

example, the preview of the item might have been sufficient

to solve the user’s information need or the user’s interest may

have been in the file’s path. Of those queries issued

by the remaining 8, users previewed at least one item

17% of the time but never opened the file’s containing

directory through our interface. To confirm our suspicions

about failed search behavior, again it would have been

beneficial to ask users as to whether their search was

successful.

Figure 7 shows a box-and-whiskers plot of each subject’s

ratings for each of the different algorithms. Subjects who

rated no queries are omitted from the plot for brevity. Some

cursory observations across all subjects are that the causality

algorithm usually performs at or above content-only,

with the exception of subjects U3 and U16. Temporal

locality is on par or better than content-only for half of the

subjects, but is rated exceptionally poorly, less than a

2, for a quarter of subjects (U3, U9, U13 and U16).

Surprisingly, while the expectation is for random to be

exceedingly poor, it is often only rated a notch below other

algorithms.

Rigorous evaluation requires care as we have multiple

observations on the same subject for different queries—a

repeated measures experiment. Observations on different

subjects can be treated as independent, but observations on

the same subject cannot. Thus, we develop a mixed-effects

ANOVA model [19] to test the statistical significance of our

hypotheses.

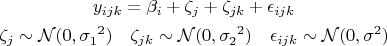

Let yijk denote the rating of the i-th algorithm by the j-th

subject for the k-th query. Our model includes three

categorical predictors: the subject (16 levels), the algorithm

(4 levels), and the queries (34 levels). For the subjects, there

is no particular interest in these individuals; rather, the goal

is to study the person-to-person variability in all persons’

opinions. For each query evaluated by each subject, we wish

to study the query-to-query variability within each subject’s

ratings. The algorithm is a fixed effect (βi), each subject then

is a random effect (ζj) with each query being a nested

random effect (ζjk). Another way to reach the same

conclusion is to note that if the experiment were repeated, thesame four algorithms would be used, since they are part of

the experimental design, but another random sample would

yield a different set of individuals and a different set of

queries executed by those individuals. Our model therefore

is:  |

(3)

|

| | | 95% Conf. Int.

| | Algorithm | βi | Lower | Upper | p-value† |

|

|

|

|

| | Content only | 3.545 | 3.158 | 3.932 |

| Causality | 4.133 | 3.746 | 4.520 | 0.0042 |

| Temp. locality | 3.368 | 2.982 | 3.755 | 0.3812 |

| Random | 2.280 | 1.893 | 2.667 | <0.0001 |

|

|

|

|

| | σ1 | 0.3829 | 0.1763 | 0.8313 |

| σ2 | 0.4860 | 0.2935 | 0.8046 |

| σ | 0.8149 | 0.7104 | 0.9347 |

| |

†In comparison to content-only.

| Table 2: | Maximum likelihood estimate of the

mixed-effects model given in equation (3). |

|

A maximum likelihood fit of (3) is presented in Table 2.

Each βi represents the mean across the population

for algorithm i. The temporal locality algorithm is

statistically indistinguishable from content-only search

(t99 = -0.880,p=0.3812), while the causality algorithm is

rated, on average, about 17% better (t99 = 2.93,p=0.0042).

Random-ranking is rated about 36% worse on average

(t99 = -6.304,p<0.0001).

Why is temporal locality statistically indistinguishable

from content-only? Based on informal interviews, we purport

the cause of these poor ratings is temporal locality’s

tendency to build relationships that exhibit post-hoc errors:

the fallacy of believing that temporal succession implies a

causal relation.

For example, U16 was a CAD user that only worked on a

handful of files for most of the tracing period (a design she

was working on). The temporal locality algorithm caused

these files to form supernodes in the relation graph; every

other file was related to them. Under results generated by

the temporal locality algorithm, each of her queries

included her CAD files bubbled to the top of the results list.

U9 was mostly working on his dissertation and every

file, as well as some of his music, was lightly related to

each other. The temporal locality algorithm created a

relation graph with 21,376 links with geometric mean

weight of 1.48 (σl=0.688); the causality algorithm,

an order of magnitude fewer, with 1,345 links and a

geometric mean weight of 9.79 (σl=1.512). In his case, it

appears that the temporal algorithm naïvely creates many

lightly-weighted superfluous relations compared with the

causality algorithm.

A user’s work habits will affect the utility of provenance

analysis techniques. Temporal locality’s tendency to

generate large numbers of lightweight false-positive

relationships can be detrimental in many cases, making more

conservative techniques such as causality more broadly

applicable.

The random reordering shares equivalent precision and

recall values as content-only search, but is rated about 35.7%

worse on average. We expect a random ordering to do

phenomenally worse, but hypothesize that personal search

tools are still in their infancy. That is, attention in the

research community has been placed on web search, and

only recently has desktop search become a priority.

There is appreciable room for improvement. It may

also be that users are simply content with having their

desired result on the first page and are apathetic to each

result’s relative ordering within that page. More work is

required to understand a user’s perception of search

orderings.

We further analyze any interactions between other

covariates such as the demographics of participants or user

features (e.g., size of disk, number of files, folder depth). Wefind these covariates either to be statistically insignificant or

to overfit our model.

5.3 Performance

Our results indicate that our causality algorithm increases

user satisfaction of personal file search. However, such a

system is only effective if minimum additional system

resources are required for building, storing, and traversing

the relation graph created by this algorithm. We eschew

discussion of content indexing overheads as these are already

known [16].

5.3.1 Tracing Performance

We measure the impact building the relation graph has on

foreground performance with the Postmark synthetic

benchmark [13]. Postmark is designed to measure file

system performance in small-file Internet server applications

such as email servers. It creates a large set of continually

changing files, measuring the transaction rates for a

workload of many small reads, writes, and deletes. While not

representative of real user activity in desktop systems,

Postmark represents a particularly harsh setup for our

collection daemon: many read and write events to a

multitude of files inside a single process. Essentially,

Postmark’s workload creates a densely-connected relation

graph.

We run 5 trials of Postmark, with and without tracing, with

50,000 transactions and 10,000 simultaneous files on an IBM

Thinkpad X24 laptop with a 1.13 GHz Pentium III-M CPU

and 640 MB of RAM, a modest machine by today’s

standards. The results are shown in Figure 8(a). Under

tracing, Postmark runs between 7.0% and 13.6% slower

(95% conf. int.; t8=7.211,p<0.001). Figure 8(b) shows a

c.d.f. of Postmark’s transaction times with and without

tracing across a single run. There is a relatively constant

attenuation under tracing, which reflects the IPC overhead of

our collection daemon and the additional disk utilization due

to relation graph updates. This additional slowdown caused

by relation graph construction is in line with other Win32

tracing and logging systems [15].

5.3.2 Space Requirements

We examine the additional space required by our relation

graphs. During the user study, the tool logged the size of

each relation graph every 15 minutes. Figure 9 shows

relation graph growth over time for the heaviest user

in our sample, U3. Each relation graph grows linearly

(r2 = 0.861 and r2 = 0.881 for causality and temporal

locality, respectively). While the worst case graph growth is

O(F2), where F is the number of files on a user’s system,

these graphs are generally very spare: most files only

have relationships to a handful of other files as a user’s

working set at any given time is very small. In one year, we

expect the causality relation graph for U3 to grow to

about 44 MB; in five years, 220 MB. This is paltry

compared to the size of modern disks and represents an

exceedingly small fraction of the user’s working set.

These results suggest that relation graph size isn’t an

obstacle.

5.3.3 Search Performance

The time to answer a query must be within reasonable

bounds for users to find the system usable. In our

implementation (§4), we bound the context-enhancing phase

to a maximum of 5 seconds.

For every query issued during the user study, we log

the elapsed wall clock time in the content-only and

context-enhancing phases. Figure 10 shows these results.

Half of all queries are answered within 0.8 seconds,

three-quarters within 2.8 seconds, but there is a heavy tail.

The context-enhancing phase takes about 67% of the entire

search process on average. We believe these current search

times are within acceptable limits.

Recall that the context-enhancing phase consists of two

distinct subphases: first, the loading of the relation graph,

followed by execution of the basic BFS algorithm (§3.2). To

understand the performance impact of these subphases,

previous queries issued by the author were re-executed, for 5

trials each under a cold cache, with the relation graph from a

6-month trace. Figure 11 shows the time spent for each

query based on the number of edges from the relation graph

loaded for that query. For non-empty graphs, loading the

relation graph took, on average, between 3.6% and 49.9%

longer (95% conf. int.) than the basic BFS subphase (paired

t15 = -2.470,p=0.026).

Both loading the relation graph and basic BFS execution

support linear increase models (r2 = 0.948 and r2 = 0.937,

respectively). This is apparent as each subphase requires both

Ω(F2) space and time, where F is the number of files on a

user’s system. As these are lower bounds, the only way to

save space and time would be to ignore some relationships. If

we could predict a priori which relationships were most

relevant, we could calculate, at the expense of accuracy,

equation (1a) for those pairs. Further, we could cluster those

relevant nodes together on disk, minimizing disk I/Os during

graph reads.

5.4 User Feedback

| Question | μ | σ |

|

|

| | I would prefer an interface that shows more information. | 3.84 | 1.34 |

| I find it easy to think of the correct search keywords. | 3.69 | 0.85 |

| I would prefer if I could look over all my machines. | 3.46 | 1.39 |

| This tool should be essential for any computer. | 3.30 | 1.25 |

| I like the interface. | 3.15 | 1.40 |

|

|

| | I would prefer if my email and web pages are included in the search results. | 3.00 | 1.58 |

| I would likely put less effort in organizing my files if I had this tool available. | 2.92 | 1.12 |

| |

| Table 3: | Additional 5-point Likert ratings asked

of treatment group users at the end of the study

period (N = 13). |

|

During the post-survey phase of our study, our questionnaire

contained additional 5-point Likert ratings. A tabulation of

subject’s responses for the treatment group are shown in

Table 3. While it’s difficult to draw concrete answers due to

the high standard deviations, we can develop some general

observations.

An area for improvement is the user interface. Our

results are presented in a list view (Figure 3), but using

more advanced search interfaces, such as Phlat [5],

that allow filtering through contextual cues may be more

useful. Different presentations, particularly timeline

visualizations, such as in Lifestreams [9], may better

harness users’ memory for their content. There is

a relatively strong positive correlation (ρ = 0.698) between

liking the interface and finding the tool essential; a better

interface will likely make the tool more palatable for

users.

Based on informal interviews, we found that participants

used our search tool as an auxiliary method of finding

content: they first look through their directory hierarchy for a

particular file, switching to keyword search after a few

moments of failed hunting. Participants neglect to use our

search tool as a first-class mechanism for finding content. A

system that is integrated into the OS, including availability

from within application “open” dialogs, may cause a

shift in user’s attitudes toward using search to find their

files.

We found it surprising that users wished to exclude email

and web pages from their search results; two-thirds of users

rate this question a three or below. Our consultations reveal

that many of these users dislike a homogeneous list of

dissimilar repositories and would rather prefer the ability to

specify which repository their information need resides

in. That is, a user knows if they’re searching for a file,

email or web page, let them easily specify which. We

needn’t focus on mechanisms to aggregate heterogeneous

forms of context spread across different repositories

into a unifying search result list, but to simply provide

an easy mechanism to refine our search to a specific

repository.

6 Personal Search Behavior

Finally, we explore the search behavior of our sample

population. Recall that, for privacy reasons, we do not log

any information about the content of users’ indices or search

results.

Our population issued 182 queries; the distribution

per user is shown in Figure 12. The average number

of queries issued per user is 6.74 (σ=6.91). Most

queries, 91%, were fresh, having never been issued

before. About 9% of search terms were for filenames.

Since Windows XP lacks a rapid search-by-filename

tool similar to UNIX’s slocate, users were employing

our tool to find the location of files they already knew

the name of. Most queries were very short, averaging

1.16 words (σ=0.462), slightly shorter than the 1.60

and 1.59 words reported for Phlat [5] and SIS [8]

respectively.

Figure 13 shows when queries are issued after installation.

A sizable portion of queries are issued relatively soon

after installation as users are playing with the tool. Even

though we warn users that search results are initially

incomplete because the content indexer has not built enough

state and the relation graph is sparse (§4), it may be

prudent to disallow searching until a reasonable index

has been built as not to create an unfavorable initial

impression.

Figure 14 shows the last access time and last modification

times of items opened after searching. The starred versions

represent last access and modification times of queries issued

at least a day after installation. During the first day,

users might be testing the tool against recent work and,

hence, recently accessed files. Anecdotal evidence of this

effect can be observed by the shifted last accessed curve.

After the warm-up period, half of all files selected were

accessed within the past 2 days. It appears users are

employing our tool to search for more than archival

data.

7 Conclusions & Future Work

By measuring users perception of search quality with our

rating task (§5.2.2), we were able to show that using

causality (§3.1.2) as the dynamic re-indexing component

increases user satisfaction in search, being rated 17% higher

than content-only indexing or temporal locality, on average

over all queries. While our contextual search mechanism

lacked any significant increases in end-to-end effects in our

randomized controlled trial (§5.2.1), this stemmed from an

insufficiently large sample size. It is prohibitively expensive

to secure such high levels of replication, making our rating

task a more appropriate methodology for evaluating personal

search systems. These results validate that using the

provenance of files to reorder and extend search results is an

important complement to content-only indexing for personal

file search.

There is still considerable future work in this area. While

we find temporal locality (§3.1.1) infelicitous in building a

contextual index, one should not dismiss temporal bounds

altogether. We are investigating using window focus

and input flows in delineating tasks to create temporal

boundaries.

Further, our tool only has limited access: a user’s

local file system. We could leverage electronic mail,

their other devices and machines, and distributed file

systems, stitching context from these stores together to

provide further benefit. Since these indices may span the

boundaries of multiple machines and administrative

domains, we must be careful to maintain user privacy

and access rights. We are investigating these and other

avenues.

Finally, the tradition in the OS community, and we have

been as guilty of this as any, has been to evaluate systems on

a small number of users—usually departmental colleagues

known to the study author. These users are generally

recognized as atypical of the computing population at large:

they are expert users. As the community turns its attention

away from performance and toward issues of usability and

manageability, we hope our work inspires the OS communityto consider evaluating their systems using the rigorous

techniques that have been vetted by other disciplines. User

studies allow us to determine if systems designed and

tested inside the laboratory are indeed applicable as we

believe.

Acknowledgements

We’d like to thank Mark Ackerman for his help with our user

study. This research was supported in part by the National

Science Foundation under grant number CNS-0509089. Any

opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations

expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not

necessarily reflect the views of the National Science

Foundation.

References

[1] Nasreen

Abdul-Jaleel, James Allan, W. Bruce Croft, Fernando Diaz, Leah

Larkey, Xiaoyan Li, Donald Metzler, Mark D. Smucker, Trevor

Strohman, Howard Turtle, and Courtney Wade. UMass at TREC

2004: Notebook. In TREC 2004, pages 657–670, 2004.

[2] James Allan, Ben Carterette, and Joshua Lewis. When will

information retrieval be “good enough”? In SIGIR 2005, pages

433–440, Salvador, Brazil, 2005.

[3] Ricardo Baeza-Yates and Berthier Ribeiro-Neto. Modern

Information Retrieval. ACM Press, New York, 1999.

[4] H. Russell Bernard. Social Research Methods. Sage

Publications Inc., 2000.

[5] Edward Cutrell, Daniel C. Robbins, Susan T. Dumais, and

Raman Sarin. Fast, flexible filtering with Phlat—personal search

and organization made easy. In CHI 2006, pages 261–270,

Montréal, Québec, Canada, 2006.

[6] Mary Czerwinski and Eric Horvitz. An investigation of

memory for daily computing events. In HCI 2002, pages

230–245, London, England, 2002.

[7] John R. Douceur and William J. Bolosky. A large-scale

study of file-system contents. In IMC 1999, pages 59–70, 1999.

[8] Susan T. Dumais, Edward Cutrell, J. J. Cadiz, Gavin Jancke,

Raman Sarin, and Daniel C. Robbins. Stuff I’ve Seen: A system

for personal information retrieval and re-use. In SIGIR 2003,

pages 72–79, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2003.

[9] Scott Fertig, Eric Freeman, and David Gelernter. Lifestreams:

An alternative to the desktop metaphor. In CHI 1996, pages

410–411, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, April 1996.

[10] David K. Gifford, Pierre Jouvelot, Mark A. Sheldon, and

James W. O’Toole. Semantic file systems. In SOSP 1991, pages

16–25, Pacific Grove, CA, October 1991.

[11] Galen Hunt and Doug Brubacher. Detours: Binary

interception of Win32 functions. In 3rd USENIX Windows NT

Symposium, pages 135–143, Seattle, WA, USA, 1999.

[12] David Huynh, David R. Karger, and Dennis Quan. Haystack:

A platform for creating, organizing and visualing information

using RDF. In Semantic Web Workshop, 2002.

[13] Jeffrey Katcher. Postmark: A new filesystem benchmark.

Technical Report 3022, Network Appliance, October 1997.

[14] David R. Krathwohl. Methods of Educational and Social

Science Research: An Integrated Approach. Waveland Inc., 2nd

edition, 2004.

[15] Jacob R. Lorch and Alan Jay Smith. The VTrace tool:

building a system tracer for Windows NT and Windows 2000.

MSDN Magazine, 15(10):86–102, October 2000.

[16] Donald Metzler, Trevor Strohman, Howard Turtle, and

W. Bruce Croft. Indri at TREC 2004: Terabyte Track. In TREC

2004, 2004.

[17] Kiran-Kumar Muniswamy-Reddy, David A. Holland, Uri

Braun, and Margo Seltzer. Provenace-aware storage systems. In

USENIX 2006, pages 43–56, Boston, MA, USA, 2006.

[18] Nuria Oliver, Greg Smith, Chintan Thakkar, and Arun C.

Surendran. SWISH: Semantic analysis of window titles and

switching history. In IUI 2006, pages 194–201, Sydney,

Australia, 2006.

[19] José C. Pinheiro and Douglas M. Bates. Mixed-Effects

Models in S and S-Plus. Springer, New York, 2000.

[20] Craig A. N. Soules. Using context to assist in personal file

retrieval. PhD thesis, Carnegie Mellon University, 2006.

[21] Craig A. N. Soules and Gregory R. Ganger. Connections:

using context to enhance file search. In SOSP 2005, pages

119–132, Brighton, UK, 2005.

[22] Jaime Teevan, Christine Alvarado, Mark S. Ackerman, and

David R. Karger. The perfect search engine is not enough: a

study of orienteering behavior in directed search. In CHI 2004,

pages 415–422, 2004.

|