SRUTI '05 Paper

[SRUTI '05 Technical Program]

Improving Spam Detection Based on Structural Similarity

Luiz H. Gomes1, Fernando D. O. Castro,

Virgílio A. F.Almeida, Jussara M. Almeida, Rodrigo B. Almeida

Computer Science Dept.,Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte - Brazil

{lhg,fernando, virgilio,jussara, barra}@dcc.ufmg.br

-

Luis M. A. Bettencourt

Computer and Computational Sciences, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos - USA

lmbett@lanl.gov

We propose a new spam detection algorithm that uses structural relationships

between senders and recipients of email as the basis for spam detection.

A unifying representation of users and receivers in the

vectorial space of their contacts is constructed, that leads to a natural definition

of similarity between them.

This similarity is then used to group email senders and recipients into clusters. Historical

information about the messages sent and received by the clusters is obtained by

forwarding messages to an auxiliary spam detection algorithm and this

information is used to reclassify messages. In the framework proposed, our algorithm aims

at correcting misclassifications from an auxiliary algorithm.

A simulation is performed based on actual data collected from an SMTP server

from a large University. We show that our approach is able reduce false positives,

produced by the auxiliary classification algorithm, up to about 60%.

1 Introduction

The relentless rise in spam email traffic, now accounting for about

of all incoming messages, up from of all incoming messages, up from  in January

2003 [14], is becoming one of the greatest threats to the

use of email as a form of communication. Spam is also increasingly at the root

of major security breaches as more viruses, worms and other malicious software makes use of

spam messages to spread throughout the Internet. in January

2003 [14], is becoming one of the greatest threats to the

use of email as a form of communication. Spam is also increasingly at the root

of major security breaches as more viruses, worms and other malicious software makes use of

spam messages to spread throughout the Internet.

A major problem in detecting spam stems from active adversarial efforts to

thwart classification. Spam senders use a multitude of techniques based on

knowledge of current algorithms, to evade detection. These techniques

range from changes in the way text is written to frequent changes in

elements, such as user names, domains, subjects, etc. Although such evasion strategies are usually

naturally understood by humans, it is hard to automatically analyze them.

A central question that remains unanswered is: what are the

identifiers of spam that are most costly to change, from the point of view of

the spammer? The limitations of attempts to recognize spam by analyzing content

are emphasized in [7]. Content-based

techniques [15,22,16] have to cope

with the constant changes in the way spammers generate their solicitations. The

structure of the target space for these solicitations tends, however, to be much

more stable since spam senders still need to reach recipients in order to be

effective. Specifically, by structure we mean the space of recipients targeted

by a spam sender, as well as the space of senders that targets a given

recipient, i.e. the contact lists of a user. The contact lists, or subsets thereof,

can then be thought of as a (dynamical) signature of spam senders and

recipients. Additionally by constructing a similarity measure in these

spaces we can track how lists evolve over time, by addition or removal of

addresses.

In this paper, we propose and evaluate an algorithm for improving spam detection that

uses structural relationships between senders and recipients as the basis for

the detection of spam messages. The algorithm works in conjunction

with another spam classifier (hereafter called auxiliary algorithm), necessary to

produce spam or legitimate mail tags on past senders and receivers, which in

turn are used to infer new ones, through structural similarity. The key idea is

that the set of distinct recipients that spammers and legitimate users send

messages to, as well as the set of distinct senders from which users

receive messages from (which, in both cases, we call contact lists), can be

used as identifiers of senders and recipients in email

traffic [19,11,12]. We show that the

application of our structural algorithms over the auxiliary

classifier's results leads to the correction of a number of misclassifications.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the

methodology used to handle email data. Our structural algorithm is described in

Section 3. We present the characteristics of the

workload studied in section 4, as well as the classification results

obtained with our algorithm over this data set. Related work is presented in

Section 5 and conclusions and future work in

Section 6.

2 Modeling Similarity Among Email Senders and Recipients

Our proposed spam detection algorithm exploits the structural

similarities in groups of senders and recipients of email.

This section introduces a unifying modeling framework of

individual email users and a metric that captures the similarity

between them.

Our basic assumption is that, in legitimate and spam traffics, users

have a list of peers they often have contact with (i.e., they

send/receive an email to/from), as can be seen in Section 4.

In legitimate traffic, contact lists stem from social relationships.

On the other hand, the lists created by spammers

to distribute their solicitations are guided by business opportunities and,

generally, do not reflect any form of social interaction.

Contact lists certainly change over time. However,

we expect them to be much less variable than other identifiers

commonly used for spam detection, such as the presence of certain keywords in

the email content or its size and encoding. In other words, we expect

contact lists to be an effective basis for detecting spam.

We start by representing an email user as a vector in a multi-dimensional

vectorial space created out of all possible contacts. We represent email senders

and recipients separately. We then use vectorial operations (the normalized

inner product in the sender/recipient spaces)

to express the similarity among multiple senders/recipients. Finally, similarity is used

to associate users into clusters. Note that the term email user is used throughout this work to

denote any identification of an email sender/recipient (e.g., email address,

domain name, SMTP relay, etc).

Let  be the number of distinct recipients. We represent a

sender be the number of distinct recipients. We represent a

sender  as a as a  dimensional vector, dimensional vector,  ,

defined in the vectorial space of email recipients.

The ,

defined in the vectorial space of email recipients.

The  -th dimension (representing recipient -th dimension (representing recipient  ) of ) of  is defined as:

is defined as:

![$\displaystyle \footnotesize\vec{s_i}[n] = \left\{ \begin{array}{ll}

1, & $ if $s_i \rightarrow r_n \\

0, & $ otherwise$\ \\

\end{array}\right.,$](img12.png) |

|

|

(1) |

where

indicates that sender indicates that sender  has sent at least one email to has sent at least one email to

recipient. recipient.

Similarly, we define  as a as a  dimensional vector representing

recipient dimensional vector representing

recipient  , where , where  is the number of distinct senders being

considered. The is the number of distinct senders being

considered. The  -th dimension of this vector is analogously set to -th dimension of this vector is analogously set to  if recipient if recipient

has received at least one email from has received at least one email from  . .

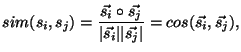

We next define the similarity between two senders  and and  as the cosine of the angle between their vectorial representation (

as the cosine of the angle between their vectorial representation ( and and  ).

The cosine is a well known metric that has

been successfully employed in several application areas, including

document similarity in information retrieval systems [3,20]

and intrusion detection [21]. This similarity metric is computed as: ).

The cosine is a well known metric that has

been successfully employed in several application areas, including

document similarity in information retrieval systems [3,20]

and intrusion detection [21]. This similarity metric is computed as:

|

|

|

(2) |

where

represents the internal product of the

vectors and represents the internal product of the

vectors and  is the norm of is the norm of  .

This metric varies between 0, when senders do not

share any recipient in their contact lists, and 1, when senders have identical

contact lists and thus have the same representation. The similarity between two

recipients is similarly defined. .

This metric varies between 0, when senders do not

share any recipient in their contact lists, and 1, when senders have identical

contact lists and thus have the same representation. The similarity between two

recipients is similarly defined.

We note that our similarity metric has different interpretations

in legitimate and spam traffics. In legitimate email traffic, it represents

social relationships that consist of interactions with the same group of users, whereas in the spam

traffic, a great similarity probably represents the use of different identifiers by

the same spammer or the sharing of distribution lists by distinct spammers.

Finally, we can use our vectorial modeling approach to represent a

cluster of senders or recipients. A sender cluster  , represented

by vector , represented

by vector  , is computed as the vector sum of its elements,

that is: , is computed as the vector sum of its elements,

that is:

|

(3) |

The similarity between a sender  and an existing cluster and an existing cluster  can be

assessed by extending Equation 2 as follows: can be

assessed by extending Equation 2 as follows:

|

|

|

(4) |

We note that the vectorial representation of a sender  and of the the sender's cluster

may change over time as new emails are considered. In order to accurately estimate the similarity

between a sender and of the the sender's cluster

may change over time as new emails are considered. In order to accurately estimate the similarity

between a sender  and a sender cluster and a sender cluster  to which to which  currently belongs to, we first remove

currently belongs to, we first remove  from from  , and then

take the cosine between the two vectors ( , and then

take the cosine between the two vectors (

and and

). This guarantees that the previous classification of a user

does not influence its new classification. Recipient clusters and

similarities are defined analogously. ). This guarantees that the previous classification of a user

does not influence its new classification. Recipient clusters and

similarities are defined analogously.

3 Structural Similarity Algorithm

This section introduces our new email classification approach, which exploits

the similarity between email senders and recipients for their association into

clusters, which are tagged by historical information.

Our algorithms is designed to work together with any

existing spam detection or filtering technique.

Our goal is to provide a significant reduction of false positives (i.e.,

legitimate emails wrongly classified as spam), which can be as high as 15% in

current filters [2].

Figure 1:

Architecture Proposed.

|

The architecture proposed in this paper is shown in

Figure 1. A message arrives at the spam detection system and

is directed to the structural similarity algorithm. This algorithm

first sends the message to the auxiliary detection algorithm to

retrieve a first classification of that message. Based on this

classification, on the cluster formed by senders and recipients, and on

previous historical information, our algorithm generates a new classification, which

may or may not coincide with the original classification provided by the auxiliary.

The idea is to use the classification provided by the auxiliary method

to build an incremental historical knowledge base that becomes more

representative as more messages are processed.

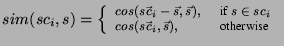

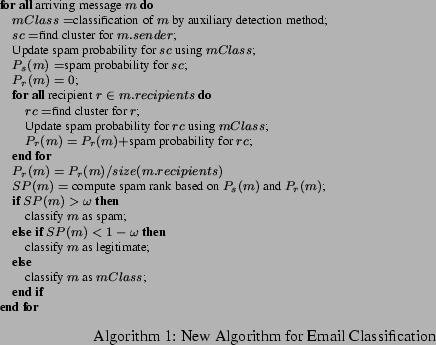

A description of the cluster-based algorithm is shown

in Algorithm 1. This algorithm maintains sets of sender and

recipient clusters, assembled from structural similarity, as defined in

Equation (4). A sender/recipient of an incoming email is added to the

sender/recipient cluster that is most similar to it, provided that their

similarity exceeds a given threshold  . Thus, . Thus,  defines the minimum

similarity a sender/recipient must have with a cluster to be assigned to it.

Varying defines the minimum

similarity a sender/recipient must have with a cluster to be assigned to it.

Varying  allows us to create more or less tightly knit

clusters. If no similar cluster can be found, a new single-user cluster is created. allows us to create more or less tightly knit

clusters. If no similar cluster can be found, a new single-user cluster is created.

The sets of sender and recipient clusters are updated at each new email arrival.

Recall that to determine the cluster of a previous classified user we first remove

the user from its current cluster and then assess its similarity to each existing cluster. Thus,

single-user clusters tend to be reduced as more emails are processed, except possibly

for users that appear only very sporadically.

A probability of sending/receiving spam messages is assigned to each sender/recipient

cluster. We refer to this measure as the cluster spam probability. We

calculate the spam probability of a sender/recipient cluster as the average

spam probability of its elements, which, in turn, is estimated from the

frequency of spams sent/received by each of them in the past. Therefore,

our scheme uses the result of the email classification performed

by the auxiliary algorithm on each arriving email  ( ( in

Algorithm 1) to continuously update cluster spam probabilities. in

Algorithm 1) to continuously update cluster spam probabilities.

Let us define the probability of a message  being sent by a spammer, being sent by a spammer,

, as the probability of its sender's cluster send a spam. Similarly, let the

probability of an email , as the probability of its sender's cluster send a spam. Similarly, let the

probability of an email  being addressed to users that receive spam, being addressed to users that receive spam,

, as the average spam probability of all of its recipients'

clusters. Our algorithm uses , as the average spam probability of all of its recipients'

clusters. Our algorithm uses  and and  to compute a

number that expresses the chance of email to compute a

number that expresses the chance of email  being spam. We call this number

the spam rank of email being spam. We call this number

the spam rank of email  , denoted by , denoted by  .

The idea is that emails with large values of .

The idea is that emails with large values of  and and  should have

large spam ranks and thus should be classified as spam messages. Similarly, emails with

small values of should have

large spam ranks and thus should be classified as spam messages. Similarly, emails with

small values of  and and  should receive low spam rank and be

classified as legitimate email. should receive low spam rank and be

classified as legitimate email.

Figure 2:

Spam Rank Computation and Email Classification for the Cluster-based

Algorithm.

|

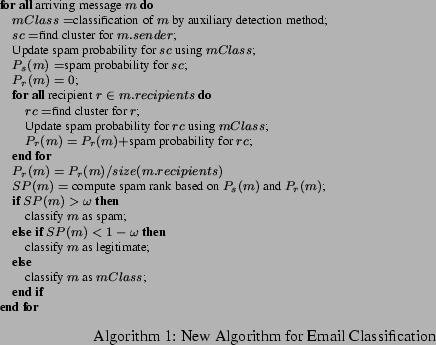

Figure 2 shows a graphical representation of the computation

of the spam rank for a message. We first normalize the probabilities  and

and  by a factor of by a factor of  , so that the diagonal of the square

region defined in the bi-dimensional space is equal to 1 (see

Figure 2-left). Each email , so that the diagonal of the square

region defined in the bi-dimensional space is equal to 1 (see

Figure 2-left). Each email  is represented as a point

in this square. The spam rank of is represented as a point

in this square. The spam rank of  , ,  , is then defined as the length of

the segment starting at the origin (0,0) and ending at the projection of , is then defined as the length of

the segment starting at the origin (0,0) and ending at the projection of  on the diagonal of the square (see Figure 2-right). With these definitions the spam rank varies between 0 and 1.

on the diagonal of the square (see Figure 2-right). With these definitions the spam rank varies between 0 and 1.

The spam rank  is then used to classify is then used to classify  as follows: if it is greater

than a given threshold as follows: if it is greater

than a given threshold  , e.g. , e.g.

, the email is classified as spam; if it is

smaller than , the email is classified as spam; if it is

smaller than  , it is classified as legitimate email. Otherwise, we can

not precisely classify the message, and we rely on the initial classification

provided by the auxiliary algorithm. The parameter , it is classified as legitimate email. Otherwise, we can

not precisely classify the message, and we rely on the initial classification

provided by the auxiliary algorithm. The parameter  can be tuned

to determine the precision of our classification.

Graphically, emails are classified according to the marked regions shown in

Figure 2-left. The two identical triangles represent the

regions where our algorithm is able to classify

emails as either spam (upper right) or legitimate email (lower left). can be tuned

to determine the precision of our classification.

Graphically, emails are classified according to the marked regions shown in

Figure 2-left. The two identical triangles represent the

regions where our algorithm is able to classify

emails as either spam (upper right) or legitimate email (lower left).

4 Experimental Results

In this section we describe our experimental results.

We first present the most relevant details of our workload,

followed by the quantitative results of our approach.

4.1 Workload

Our email workload consists of anonymized and sanitized SMTP logs of incoming

emails to a large university in Brazil, with around 22,000 students. The

server handles all emails coming from domains

outside the university, sent to students, faculty and staff with

email addresses under the university's domain name Only the

emails addressed to two out of over 100 university subdomains (i.e.,

departments, research labs, research groups) do not pass through the central

server..

The central email server runs Exim email software [10],

the AMaViS virus scanner [1] and the Trendmicro

Vscan anti-virus tool [17]. A set of pre-acceptance

spam filters (e.g. black lists, DNS reversal) blocks about 50% of the total traffic

received by the server.

The messages not rejected by the pre-acceptance tests are directed to

Spam-Assassin [16]. Spam-Assassin is a popular spam filtering

software that detects spam messages based on a changing set of user-defined

rules. These rules assign scores to each email received, based on the presence

in the subject or in the email body of one or more pre-categorized

keywords. Spam-Assassin also uses other rules based on message size

and encoding. Highly ranked messages according to these criteria are flagged

as spam.

We analyze a log collected from 01/02/2004 to 01/10/2004.

Our logs store the header of each email (i.e. containing sender, recipients, size , date, etc.)

that passes the pre-acceptance filters, along with the results of the tests performed by

Spam-Assassin and the virus scanners. We also have the full body of the messages

that were classified as spam by Spam-Assassin. Table 1 summarizes our

workload.

Table 1:

Summary of the Workload

|

Measure |

Non-Spam |

Spam |

Aggregate |

|

# of emails |

168,352 |

153,494 |

321,846 |

|

Size of emails |

7.5 GB |

0.8 GB |

8.3 GB |

|

# of distinct senders |

12,738 |

15,325 |

22,809 |

|

# of distinct recipients |

23,849 |

25,383 |

34,065 |

|

By visually inspecting the list of sender user names

2

in the spam component of our workload, we

found that a large number of them corresponded to a random sequence

of characters, suggesting that spammers tend to change user names as an evasion

technique. Therefore, for the experiments presented below we identified the

sender of a message by his/her domain3

while recipients were identified by their full address.

Figure 3:

Number of Email User Clusters and Beta CV vs.  . .

|

The results shown in this section were obtained through the simulation of

the algorithm proposed in this paper over the set of messages in our logs. The

implementation of the simulator makes use of an inverted list [20]

approach for storing information about senders, recipients and clusters that is

effective both in terms of memory and processing time.

The classification rate of the simulations were both higher than the

peak rate observed over the workload collection time [12].

The number and quality of the clusters generated through our similarity

measure are the direct result of the chosen value for the threshold  (see

Section 3). In order to determine the best parameter value

the simulation was executed several times for varying (see

Section 3). In order to determine the best parameter value

the simulation was executed several times for varying  . .

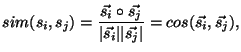

Figure 3 shows how the beta CV (Coefficient of Variation)

for the clusters and the number of clusters vs.  . Beta CV denotes the intra

CV/inter CV for the clusters. Whereas the intra CV measures the coefficient of variation for

the similarities intra-cluster, the inter CV measure the similarities between

different clusters. Thus, beta CV is a measure of the quality of the clusters generated.

The more stable the beta CV the better quality in

terms of the grouping obtained [13]. There is one clear point of

stability in the curve at . Beta CV denotes the intra

CV/inter CV for the clusters. Whereas the intra CV measures the coefficient of variation for

the similarities intra-cluster, the inter CV measure the similarities between

different clusters. Thus, beta CV is a measure of the quality of the clusters generated.

The more stable the beta CV the better quality in

terms of the grouping obtained [13]. There is one clear point of

stability in the curve at  (Figure 3(a)).

Moreover, the number of clusters generated also stabilize at (Figure 3(a)).

Moreover, the number of clusters generated also stabilize at  (Figure 3(b)). This is the value we adopt for the

remaining of the paper. Although other values of

(Figure 3(b)). This is the value we adopt for the

remaining of the paper. Although other values of  , above , above  would also

be appropriate, the value of would also

be appropriate, the value of  results in a large number of non

unitary clusters, allowing us to evaluate the benefits of the clustering

of senders and recipients. results in a large number of non

unitary clusters, allowing us to evaluate the benefits of the clustering

of senders and recipients.

Our approach is motivated by two hypothesis. First, contact lists of email

users provide an effective means for identifying them. Second, messages can be

more accurately classified as spam or not based on the probabilities of sending/receiving

spams of the cluster that their sender/recipients belong to.

Figure 4:

Spam Senders Identification Stabilization

[Mean Cosine] ![\includegraphics[width=110pt]{plots/cosStabilization.eps}](img45.png)

[CV of Cosine] ![\includegraphics[width=110pt]{plots/cvStabilization.eps}](img46.png)

|

In order to show that contact lists provide an effective user identification,

we analyze how sender/recipient vectorial representations change over time,

as new messages arrive in the system. In this analysis, we consider a warm-up

period containing a certain fraction of the messages, during which

sender/recipients are updated. We define  as the vectorial

representation of sender as the vectorial

representation of sender  at a point in time when it had sent at a point in time when it had sent

of its own messages ( of its own messages ( is larger than the warm-up period).

We use the similarity between the representations of sender is larger than the warm-up period).

We use the similarity between the representations of sender  in

two points in time, spaced by a certain fraction in

two points in time, spaced by a certain fraction  of

messages sent, as a measure of how stable the sender identification

is over ``period" of

messages sent, as a measure of how stable the sender identification

is over ``period"  . We then analyze how this similarity, given by . We then analyze how this similarity, given by

evolves as the step evolves as the step  increases.

Figure 4(a) shows average similarity measures for the

senders in the spam traffic, varying the step from increases.

Figure 4(a) shows average similarity measures for the

senders in the spam traffic, varying the step from  to to  ,

for different warm-up periods. Figure 4(b) shows the

corresponding measures of coefficient of variation (CV). Note that, as

expected, when there is no warm-up period (``No Warming"), fluctuations

in the early messages dominate and stabilization is not reached by the

end of our workload. In other words, a larger set of messages

would be required for stabilization to be reached. As the warm-up period

increases, stabilization is reached with a smaller number of messages.

In particular, when we consider only the last 25% of the messages for

each sender (``Warming of 75%"), sender representation remains,

on average, very stable with CV approaching zero. Similar patterns were

observed for legitimate e-mail senders as well as legitimate and spam recipients. ,

for different warm-up periods. Figure 4(b) shows the

corresponding measures of coefficient of variation (CV). Note that, as

expected, when there is no warm-up period (``No Warming"), fluctuations

in the early messages dominate and stabilization is not reached by the

end of our workload. In other words, a larger set of messages

would be required for stabilization to be reached. As the warm-up period

increases, stabilization is reached with a smaller number of messages.

In particular, when we consider only the last 25% of the messages for

each sender (``Warming of 75%"), sender representation remains,

on average, very stable with CV approaching zero. Similar patterns were

observed for legitimate e-mail senders as well as legitimate and spam recipients.

Figure 5:

Number of Spam Messages by Varying Message Spam Probabilities for

Different Bin Sizes.

[Bin size = 0.10] ![\includegraphics[width=110pt]{plots/spamSurface_0.10_0.5.eps}](img54.png)

[Bin size = 0.25] ![\includegraphics[width=110pt]{plots/spamSurface_0.25_0.5.eps}](img55.png)

|

Next, we investigate whether the second hypothesis hold.

We plot, in figure 5, the fraction of spam

messages in our workload for different values of  and and

grouped based on a discretization of the full space represented in the

plot. This space is subdivided into smaller squares of the same size called

bins, the darker the gray scale the greater the number of

spams in each bin. Clearly, spam and legitimate messages are located on the top-right and

bottom-left regions of the spectrum as we have hypothesized in

Section 3. There is, however, an intermediate region in the middle where we

cannot satisfactorily determine the classification. This is why it becomes necessary to vary grouped based on a discretization of the full space represented in the

plot. This space is subdivided into smaller squares of the same size called

bins, the darker the gray scale the greater the number of

spams in each bin. Clearly, spam and legitimate messages are located on the top-right and

bottom-left regions of the spectrum as we have hypothesized in

Section 3. There is, however, an intermediate region in the middle where we

cannot satisfactorily determine the classification. This is why it becomes necessary to vary  .

One should adjust .

One should adjust  based on the level of confidence it has on the auxiliary algorithm. based on the level of confidence it has on the auxiliary algorithm.

Figure 5 shows that messages addressed to recipients that

have high  tend to be spam more frequently than messages with the same

value of tend to be spam more frequently than messages with the same

value of  . Analogously, messages with low . Analogously, messages with low  have higher probability

of being legitimate messages. have higher probability

of being legitimate messages.

Figure 6:

Messages Classified in Accordance With to the Auxiliary Algorithm and the Total

Number of Messages Classified by Varying

[Legitimate] ![\includegraphics[width=110pt]{plots/omega_Ham_0.5.eps}](img56.png)

[Spam] ![\includegraphics[width=110pt]{plots/omega_Spam_0.5.eps}](img57.png)

|

Because our algorithm makes use of an auxiliary spam detection algorithm - e.g.

SpamAssassin. Therefore, we need to evaluate how frequently we maintain the

same classification as such an algorithm. Figure 6 shows the

the percentage of messages that received the same classification and the total

number of classified messages in our simulation by varying  , considering

only messages classified by the auxiliary as legitimate (Figure 6(a)) and spam (Figure 6(b)). The difference between these curves is the set

of messages that were classified differently from the original classification. , considering

only messages classified by the auxiliary as legitimate (Figure 6(a)) and spam (Figure 6(b)). The difference between these curves is the set

of messages that were classified differently from the original classification.

Figures 6 also shows that, considering the sets of messages

originally classified as legitimate and as spam, our algorithm is capable of

classifying a larger number of messages from the former than from the latter.

Moreover, we are slightly more conservative in the classification

of legitimate emails than spams. We conjecture that both phenomena stem from the

fact that the rules used by Spam Assassin tend to favor the detection

of legitimate messages.

In another experiment, we simulated a different algorithm that also makes

use of historical information provided by an auxiliary spam detector

described in [19].

The main differences are that it uses historical information of each

sender separately and it does not use recipients information. We built

a simulator for this algorithm and executed it against our data set.

The results show that it was

able to classify  of the messages in accordance

with the auxiliary algorithm, while our approach classify more than 95% with of the messages in accordance

with the auxiliary algorithm, while our approach classify more than 95% with  . .

We believe that the differences between the original classification and the

classification proposed for high  values generally are due to

misclassifications by the auxiliary algorithm. In our data set we have access to

the full body of the messages that were originally classified as spam. We

were able to evaluate a fraction of the total amount of false positives (messages that

the auxiliary algorithm classify as spam and our algorithm classify as

legitimate) that were generated by the auxiliary algorithm. This is

important since the cost of false positives is usually believed higher

than the cost of false negatives [7]. values generally are due to

misclassifications by the auxiliary algorithm. In our data set we have access to

the full body of the messages that were originally classified as spam. We

were able to evaluate a fraction of the total amount of false positives (messages that

the auxiliary algorithm classify as spam and our algorithm classify as

legitimate) that were generated by the auxiliary algorithm. This is

important since the cost of false positives is usually believed higher

than the cost of false negatives [7].

Table 2:

Possible False Positives Generated by the Approaches Studied.

|

Algorithm |

% of Misclassifications |

|

Auxiliary |

|

|

Our approach |

|

|

Each of the possible messages classified by the auxiliary

as spam and by our algorithm as legitimate was manually evaluated by three people, in order to

determine whether such a message was indeed spam. Table 2

summarizes the results for  , 879 messages ( , 879 messages ( of the total messages)

were manually analyzed. Our algorithm was correct in more 60% of the cases. of the total messages)

were manually analyzed. Our algorithm was correct in more 60% of the cases.

Due to the cost of manually classifying messages we can not afford to classify all

of the messages categorized as spam by the auxiliary algorithm. However, we

evaluate a randomly chosen fraction of the messages classified as spam by the

auxiliary and by our algorithm, which represents the total data with a confidence

interval of 99% [18]. With  , we found that , we found that  of the

total messages are in this group and we analyzed manually

a sample of of the

total messages are in this group and we analyzed manually

a sample of  (1,708 emails) of them. We found that 99.9% of the analyzed messages were

correctly classified, showing the high precision of our classification. (1,708 emails) of them. We found that 99.9% of the analyzed messages were

correctly classified, showing the high precision of our classification.

Moreover, only  of the total of messages classified as legitimate

by the auxiliary were found to be spam by our approach. Consequently,

the total number of messages correctly moved from spam class to legitimate class is 47% greater

than the number of messages moved from legitimate class to spam class by our algorithm.

Moreover, we emphasize that we can not determine the quality of the classification for the

messages classified as legitimate by the auxiliary algorithm since we do not have

access to the full body of those messages. of the total of messages classified as legitimate

by the auxiliary were found to be spam by our approach. Consequently,

the total number of messages correctly moved from spam class to legitimate class is 47% greater

than the number of messages moved from legitimate class to spam class by our algorithm.

Moreover, we emphasize that we can not determine the quality of the classification for the

messages classified as legitimate by the auxiliary algorithm since we do not have

access to the full body of those messages.

5 Related Work

Several previous studies have focused on reducing the impact of spam email traffic.

The approaches to reduce spam can be categorized into pre-acceptance and

post-acceptance methods, based on whether they detect spam before

or after accepting messages. Examples of pre-acceptance methods

are server authentication [8,4] and

accountability [6]. Post-acceptance methods are mostly based on

information available in the body of the messages and include Bayesian

filters [15] and collaborative filtering [22].

Recent papers have focused on spam combat techniques based

on characteristics of graph models of email

traffic [5,9]. In [5] a graph is

created to represent the email traffic captured in the mailbox of individual users.

The clustering coefficient of each of these components is used to

classify messages as spam or legitimate. The results show that 53% of

the messages were precisely classified using the proposed approach. In [9] the

authors propose to detect machines that behave as spam senders by analyzing

a border flow graph of sender and recipient machines. In contrast to these studies,

we propose to use a structural similarity between email senders and recipients to group

them into clusters and use the cluster historical information to

improve spam detection. Moreover, unlike [5], our approach runs on the ISP level.

None of the existing spam filtering mechanisms are

infallible [19,7]. Their main handicap are false positives and

wrong mail classification. In addition, filters must

be continuously updated to capture the multitude of mechanism constantly

introduced by spammers to avoid filtering actions. The algorithm presented in

this paper aims at improving the effectiveness of spam filtering mechanisms,

by reducing false positives and by providing information to tune their collection of rules.

6 Conclusions and Future Work

In this paper we proposed a new algorithm to improve spam detection

based on the structural similarity between contact lists

of email users. The idea is that contact lists, integrated

over a suitable amount of time, are much more stable identifiers

of email users than user names, domains

or message contents, which can all be made to vary quickly and widely.

The major drawback of our approach is that our algorithm can only group

users based on their structural

similarity, but has no way of determining by itself if such vector

clusters correspond to spam or legitimate email. Thus it must work

in tandem with an original classifier. Given this information

we have shown that we can successfully separate

spam and legitimate email users and that this structural

inference can improve the quality of other spam detection algorithms.

Specifically we have implemented a simulator based on data collected

from the main SMTP server for a major university in Brazil that uses

SpamAssassin. We have shown that our algorithm can be tuned to

produce classifications similar to those of the original

classifier algorithm and that, for a certain set of parameters,

is was capable of correcting false positives.

As future work, we intend to: (i) explore aging mechanisms to

update the vectorial identification of senders and recipients

over time, and (ii) study the robustness of our approach against

different auxiliary classifiers.

- 1

-

AMaViS - Home Page.

http://www.amavis.org.

- 2

-

ATKINS, S.

Size and Cost of the Problem.

In Proc. 56th IETF Meeting (San Francisco, California, USA,

March 2003).

- 3

-

BAEZA-YATES, R., AND RIBEIRO-NETO, B.

Modern Information Retrieval.

Addison Wesley Longman Publishing Co. Inc., 1999.

- 4

-

BAKER, H. P.

Authentication Approaches.

In Proc. 56th IETF Meeting (San Francisco, California, USA,

March 2003).

- 5

-

BOYKIN, P. O., AND ROYCHOWDHURY, V.

Leveraging Social Networks to Fight Spam.

IEEE Computer 38, 4 (April 2005), 61-68.

- 6

-

BRANDMO, H. P.

Solving Spam by Establishing a Platform for Sender

Accountability.

In Proc. 56th IETF Meeting (San Francisco, California, USA,

March 2003).

- 7

-

CERF, V. G.

Spam, Spim, and Spit.

Commun. ACM 48, 4 (2005), 39-43.

- 8

-

CRANOR, L. F., AND LAMACCHIA, B. A.

Spam!

Communications of the ACM 41-8 (August 1998), 74-83.

- 9

-

DESIKAN, P., AND SRIVASTAVA, J.

Analyzing Network Traffic to Detect E-Mail Spamming

Machines.

In Proc. ICDM Workshop on Privacy and Security Aspects of Data

Mining (Brighton UK, November 2004), pp. 67-76.

- 10

-

Exim Internet Mailer Home Page.

http://www.exim.org.

- 11

-

GOMES, L. H., ALMEIDA, R. B., BETTENCOURT, L. M. A., ALMEIDA, V. A. F.,

AND ALMEIDA, J. M.

Comparative Graph Theoretical Characterization of Networks

of Spam and Regular Email.

http://www.arxiv.org/abs/cs.CR/0504012, March 2005.

- 12

-

GOMES, L. H., CAZITA, C., ALMEIDA, J., ALMEIDA, V. A. F., AND JR., W. M.

Characterizing a Spam Traffic.

In Proc. 4th ACM SIGCOMM Conference on Internet Measurement

(Taormina, Italy, 2004), ACM Press, pp. 356-369.

- 13

-

MENASC´E, D., AND ALMEIDA, V.

Capacity Planning for Web Services: Metrics, Models

and Methods.

Prentice Hall Inc., USA, September 2001.

- 14

-

Message Labs Home Page.

http://www.messagelabs.co.uk/.

- 15

-

SAHAMI, M., DUMAIS, S., HECKERMAN, D., AND HORVITZ, E.

A Bayesian Approach to Filtering Junk E-Mail.

Tech. Rep. WS-98-05, AAAI Workshop on Learning for Text

Categorization, Madison, Wisconsin, July 1998.

- 16

-

SpamAssassin Home Page.

http://www.spamassassin.org.

- 17

-

Trend Micro Home Page.

http://www.trendmicro.com.

- 18

-

TRIVEDI, K. S.

Probability and Statistics with Reliability, Queuing,

and Computer Science Applications.

John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY, 2001.

- 19

-

TWINING, R. D., WILLIANSON, M. M., MOWBRAY, M., AND RAHMOUNI, M.

Email Prioritization: Reducing Delays on Legitimate Mail

Caused by Junk Mail.

In Proc. Usenix Annual Technical Conference (Boston, MA, June

2004), pp. 45-58.

- 20

-

WITTEN, I. H., BELL, T. C., AND MOFFAT, A.

Managing Gigabytes: Compressing and Indexing Documents

and Images.

John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, NY, USA, 1994.

- 21

-

XIE, Y., KIM, H., O'HALLARON, D., REITER, M., , AND ZHANG, H.

Seurat: A Pointillist Approach to Anomaly Detection.

In Proc. of the 7th International Symposium on Recent Advances

in Intrusion Detection (RAID2004) (Sophia Antipolis, French Riviera,

France, September 2004), Springer Verlag, pp. 238 - 257.

- 22

-

ZHOU, F., ZHUANG, L., ZHAO, B., HUANG, L., JOSEPH, A., AND KUBIATOWICZ,

J.

Approximate Object Location and Spam Filtering on

Peer-to-Peer Systems.

In Proc. Middleware (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, January 2003),

pp. 1-20.

Improving Spam Detection Based on Structural Similarity

This document was generated using the

LaTeX2HTML translator Version 2K.1beta (1.48)

Copyright © 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996,

Nikos Drakos,

Computer Based Learning Unit, University of Leeds.

Copyright © 1997, 1998, 1999,

Ross Moore,

Mathematics Department, Macquarie University, Sydney.

The command line arguments were:

latex2html -split 0 -show_section_numbers -local_icons sruti.tex

The translation was initiated by Fernando Duarte Oliveira Castro on 2005-05-25

Footnotes

- ... Gomes1

- Luiz H. Gomes is supported by Banco Central do

Brasil.

- ... names2

- The part before @ in email addresses

- ... domain3

- The part after @ of an email address

Fernando Duarte Oliveira Castro

2005-05-25

|

![\includegraphics[width=110pt]{plots/spamSurface_0.10_0.5.eps}](img54.png) [Bin size = 0.25]

[Bin size = 0.25]![\includegraphics[width=110pt]{plots/spamSurface_0.25_0.5.eps}](img55.png)

![]() and

and

![]() grouped based on a discretization of the full space represented in the

plot. This space is subdivided into smaller squares of the same size called

bins, the darker the gray scale the greater the number of

spams in each bin. Clearly, spam and legitimate messages are located on the top-right and

bottom-left regions of the spectrum as we have hypothesized in

Section 3. There is, however, an intermediate region in the middle where we

cannot satisfactorily determine the classification. This is why it becomes necessary to vary

grouped based on a discretization of the full space represented in the

plot. This space is subdivided into smaller squares of the same size called

bins, the darker the gray scale the greater the number of

spams in each bin. Clearly, spam and legitimate messages are located on the top-right and

bottom-left regions of the spectrum as we have hypothesized in

Section 3. There is, however, an intermediate region in the middle where we

cannot satisfactorily determine the classification. This is why it becomes necessary to vary ![]() .

One should adjust

.

One should adjust ![]() based on the level of confidence it has on the auxiliary algorithm.

based on the level of confidence it has on the auxiliary algorithm.

![]() tend to be spam more frequently than messages with the same

value of

tend to be spam more frequently than messages with the same

value of ![]() . Analogously, messages with low

. Analogously, messages with low ![]() have higher probability

of being legitimate messages.

have higher probability

of being legitimate messages.

![\includegraphics[width=110pt]{plots/omega_Ham_0.5.eps}](img56.png) [Spam]

[Spam]![\includegraphics[width=110pt]{plots/omega_Spam_0.5.eps}](img57.png)

![]() , considering

only messages classified by the auxiliary as legitimate (Figure 6(a)) and spam (Figure 6(b)). The difference between these curves is the set

of messages that were classified differently from the original classification.

, considering

only messages classified by the auxiliary as legitimate (Figure 6(a)) and spam (Figure 6(b)). The difference between these curves is the set

of messages that were classified differently from the original classification.

![]() of the messages in accordance

with the auxiliary algorithm, while our approach classify more than 95% with

of the messages in accordance

with the auxiliary algorithm, while our approach classify more than 95% with ![]() .

.

![]() values generally are due to

misclassifications by the auxiliary algorithm. In our data set we have access to

the full body of the messages that were originally classified as spam. We

were able to evaluate a fraction of the total amount of false positives (messages that

the auxiliary algorithm classify as spam and our algorithm classify as

legitimate) that were generated by the auxiliary algorithm. This is

important since the cost of false positives is usually believed higher

than the cost of false negatives [7].

values generally are due to

misclassifications by the auxiliary algorithm. In our data set we have access to

the full body of the messages that were originally classified as spam. We

were able to evaluate a fraction of the total amount of false positives (messages that

the auxiliary algorithm classify as spam and our algorithm classify as

legitimate) that were generated by the auxiliary algorithm. This is

important since the cost of false positives is usually believed higher

than the cost of false negatives [7].

![]() , 879 messages (

, 879 messages (![]() of the total messages)

were manually analyzed. Our algorithm was correct in more 60% of the cases.

of the total messages)

were manually analyzed. Our algorithm was correct in more 60% of the cases.

![]() , we found that

, we found that ![]() of the

total messages are in this group and we analyzed manually

a sample of

of the

total messages are in this group and we analyzed manually

a sample of ![]() (1,708 emails) of them. We found that 99.9% of the analyzed messages were

correctly classified, showing the high precision of our classification.

(1,708 emails) of them. We found that 99.9% of the analyzed messages were

correctly classified, showing the high precision of our classification.

![]() of the total of messages classified as legitimate

by the auxiliary were found to be spam by our approach. Consequently,

the total number of messages correctly moved from spam class to legitimate class is 47% greater

than the number of messages moved from legitimate class to spam class by our algorithm.

Moreover, we emphasize that we can not determine the quality of the classification for the

messages classified as legitimate by the auxiliary algorithm since we do not have

access to the full body of those messages.

of the total of messages classified as legitimate

by the auxiliary were found to be spam by our approach. Consequently,

the total number of messages correctly moved from spam class to legitimate class is 47% greater

than the number of messages moved from legitimate class to spam class by our algorithm.

Moreover, we emphasize that we can not determine the quality of the classification for the

messages classified as legitimate by the auxiliary algorithm since we do not have

access to the full body of those messages.

![\includegraphics[width=160pt]{figures/archlhg.eps}](img31.png)

![\includegraphics[width=160pt]{figures/spamRank.eps}](img38.png)

![\includegraphics[width=150pt]{plots/tauxncomm.eps}](img42.png)

![\includegraphics[width=110pt]{plots/cosStabilization.eps}](img45.png) [CV of Cosine]

[CV of Cosine]![\includegraphics[width=110pt]{plots/cvStabilization.eps}](img46.png)