|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

HotOS IX Paper

[HotOS IX Program Index]

High Availability, Scalable Storage, Dynamic Peer Networks: Pick Two

Charles Blake Rodrigo Rodrigues

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||

2.3 Understanding the Scaling

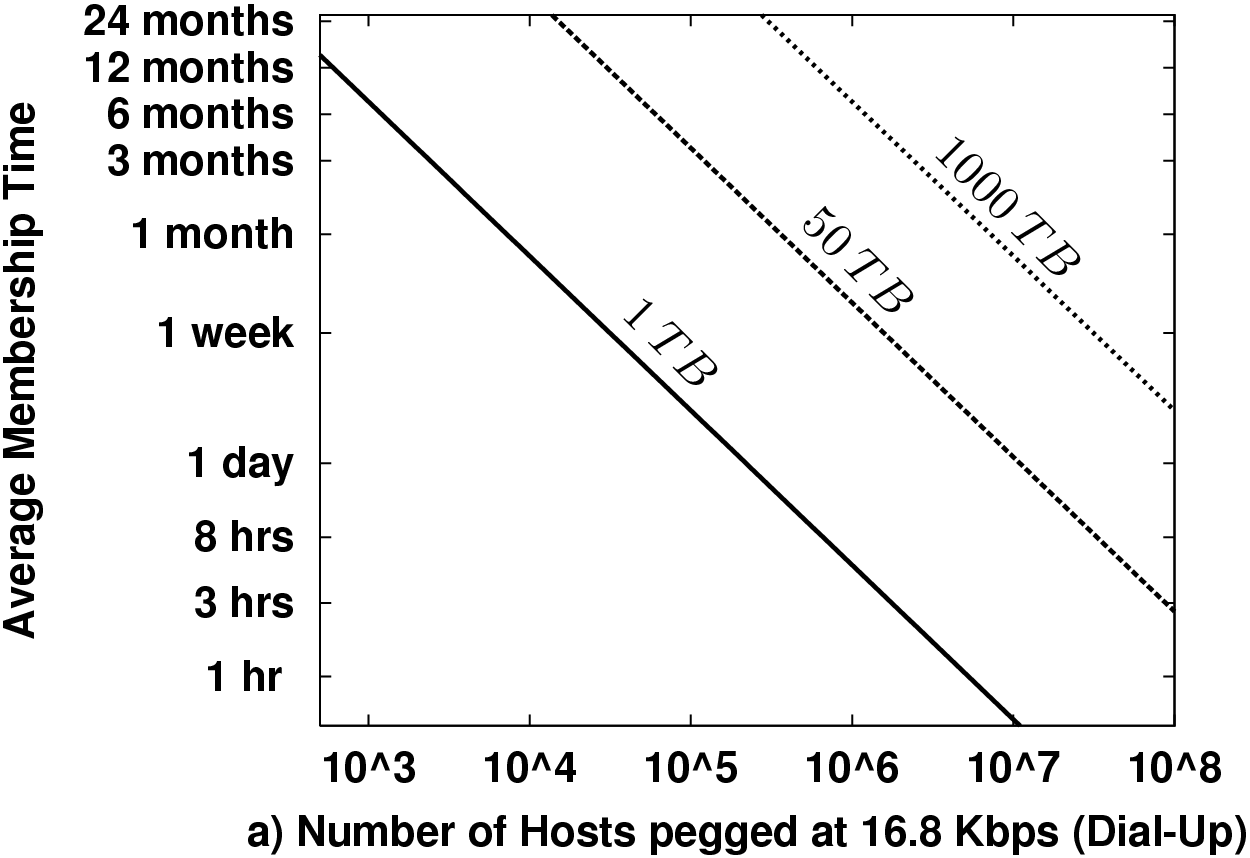

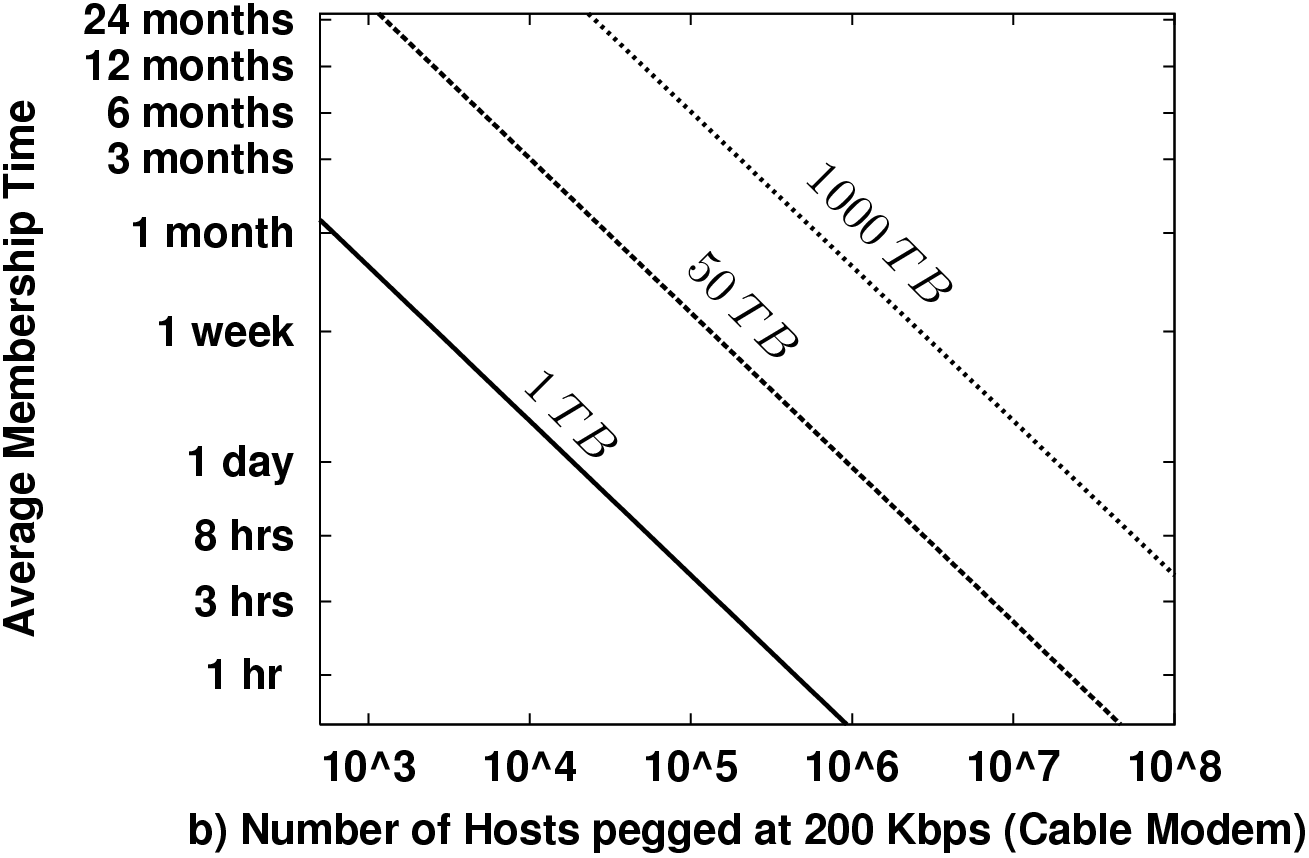

Figure 1 plots some example "threshold curves" in the lifetime-membership plane. This is the basic participation space of the system. More popular systems will have more hosts, and those hosts will stay members longer. Points below a line for a particular data scale require data maintenance bandwidth in excess of the available bandwidth. We plot thresholds for maintenance alone consuming half the total link capacity for dial-ups and cable modems. The data scales we chose, 1 TB, 50 TB, and 1000 TB, might very roughly correspond to a medium-sized music archive, a large music archive, and a small video archive (a few thousand movies), respectively.

There are two basic points to take away from these plots. First, short membership times create a need for enormous node counts to support interesting data scales. E.g., a million cable modem users must each provide a continuous month of service to maintain 1000 TB even if no one ever actually queries the data! Second, this strongly impacts how fast the storage of such a network can grow. At a monthly turnover rate, each cable modem must contribute less than 1 GB of unique data, or 20 GB of total storage. Given that PCs last only a few years and a few years ago 80 GB disks were standard on new PCs, 20 GB is likely about or below current idle capacity.

Figure 1 uses a fixed redundancy factor k = 20. The actual redundancy necessary depends on T, N, probability targets for data loss or availability. Section 3 examines in more detail the necessary k for both replication-style and erasure coded redundancy for availability.

So far our calculations have assumed that the resources a host contributes are always available. Real hosts vary greatly in availability [Bhagwan et al., 2003, Bolosky et al., 2000, Saroiu et al., 2002]. The previous section shows that it takes a lot of bandwidth to preserve redundancy upon departures. So it helps to distinguish true departures from temporary downtime, as in [Bhagwan et al., 2003].

Our model for how systems distinguish true departures from transient failures is a membership timeout, &tau, that measures how long the system delays its response to failures. I.e., the process of making new hosts responsible for a host's data does not begin until that host has been out of contact for longer than time &tau.

Counting offline hosts as members has two consequences. First, member lifetimes are longer since transient failures are not considered leaves. Second, hosts serve data for a fraction of the time that they are members (or a fraction of members serve data at a given moment). We define this fraction to be the availability, a.

Since only a fraction of the members serve data at a time, more redundancy is needed to achieve the same level of availability. Also, the effective bandwidth contributed per node is reduced since these nodes serve only a fraction of the time. Thus, the membership lifetime benefits gained by delayed response to failures are offset by the need for increased redundancy and reduced effective bandwidth. To understand this effect more quantitatively we must first know the needed redundancy.

First we compute the data expansion needed for high availability in the context of replication-style redundancy. Note that availability implies reliability since lost data is inherently unavailable.

Average lifetime now depends on timeout: T = T&tau. System size and availability also depend on &tau, and N&tau = N0/a&tau, by our definition of availability.

We wish to know the replication factor, ka, needed to achieve some per object unavailability target, &epsilona. (I.e., 1-&epsilona has some "number of 9s".)

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| (2) |

We can now evaluate the tradeoff between data maintenance bandwidth and membership timeout. We account for partial availability by replacing B with a&tau B in Equation (1). Solving for B/N and substituting Equation (2) gives:

| (3) |

To apply Equation (3) we must know N&tau, a&tau, and T&tau, which all depend upon participant behavior. We estimate these parameters using data we collected in a measurement study of the availability of hosts in the Gnutella file sharing network. We used a methodology similar to a previous study [Saroiu et al., 2002], except that we allowed our crawler to extract the entire membership, therefore giving us a precise estimate of N&tau. Our measurements took place between April 11, 2003 and April 19, 2003.

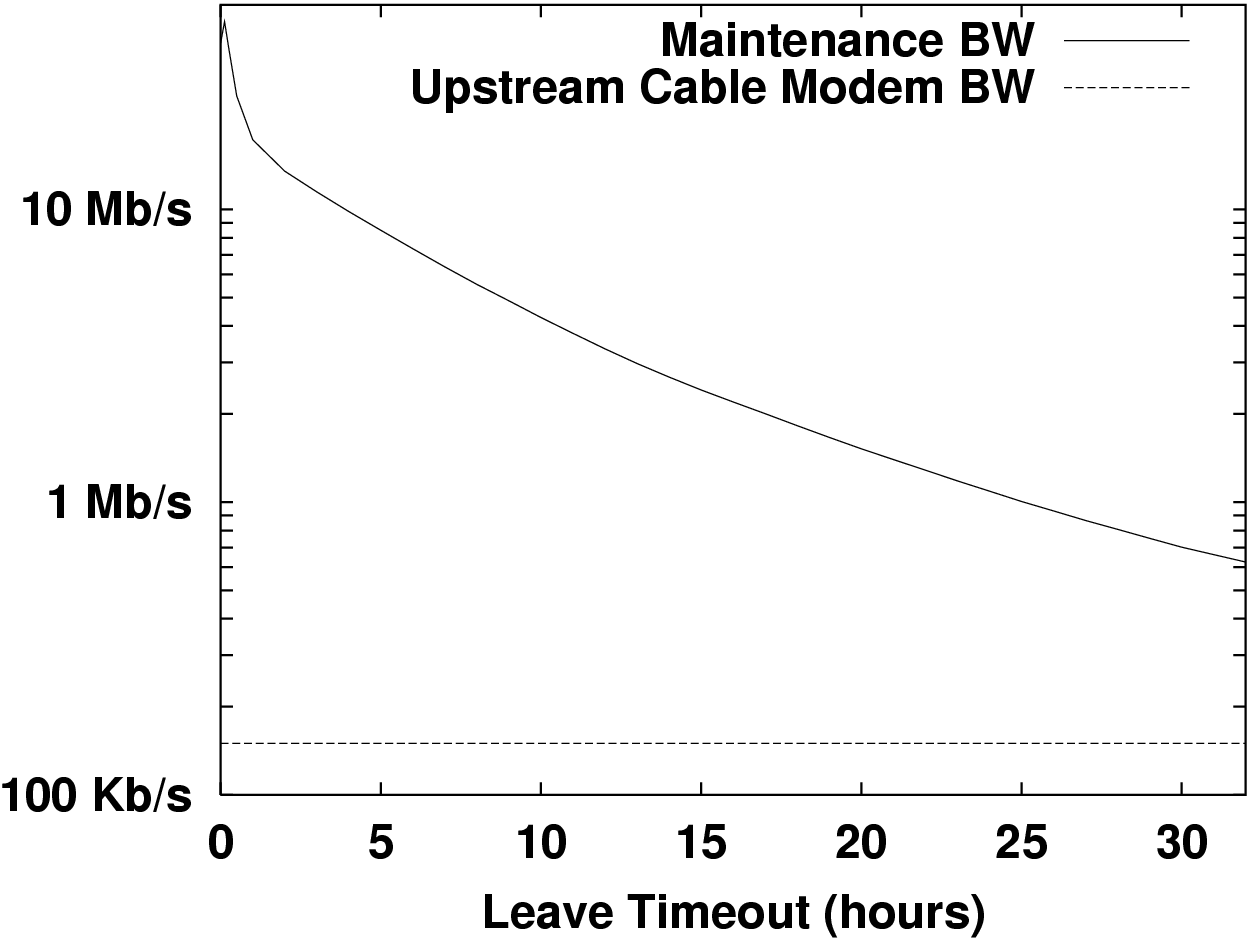

Figure 2 suggests that discriminating downtime from departure can lead to a factor of 30 savings in maintenance bandwidth. It seems hopeless to field even 1 TB at high availability with Gnutella-like participation.

A technique that has been proposed by several systems is the use of erasure coding [Weatherspoon and Kubiatowicz, 2002,]. This is more efficient than conventional replication since the increased intra-object redundancy allows the same level of availability to be achieved with much smaller additional redundancy. We now exhibit the analogue of Equation (2) for the case of erasure coding.

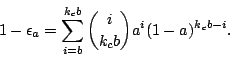

With an erasure-coded redundancy scheme, each object is divided into b blocks which are then stored with an effective redundancy factor kc. The object can be reconstructed from any available m blocks taken from the stored set of kc b blocks (where m ≈ b). Object availability is given by the probability that at least b out of kc b blocks are available:

Using algebraic simplifications and the normal approximation to the binomial distribution (see [Bhagwan et al., 2002]), we get the following formula for the erasure coding redundancy factor and then expand it in a Taylor series:

&sigma&epsilon is the number of standard deviations in a normal distribution for the required level of availability, as in [Bhagwan et al., 2002]. E.g., &sigma&epsilon = 4.7 corresponds to six nines of availability.

Figure 3 shows the benefits of coding over replication when one uses b = 15 fragments. Rather than a replication factor of 120, one can achieve the same availability with only 15 times the storage using erasure codes, for large values of &tau, an 8-fold savings. This makes it borderline feasible to store 1 TB of unique data with Gnutella-like participation and about 75 Kbps while-up per node maintenance bandwidth. Utilization is correspondingly lower for the same amount of unique data. Only 500 MB of disk per host is contributed. This is surely less than what peers are willing to donate.

Note that all of this is for maintenance only. It would be odd to engineer such highly availabile data and not read it. An actual load is hard to guess, but, as a rule of thumb, one would probably like maintenance to be less than half the total bandwidth. So, the total load one might expect would be greater than 150 Kbps or just at the limit of what cable modems can provide.

This is also not very much service. Only 5,000 of the 33,000 Gnutella hosts were usually available. If all these hosts were cable modems, the aggregate bandwidth available would be about 500 Mbps, or 250 Mbps if half that is used for data maintenance. By comparison, the same level of service could be provided by five reliable, dedicated PCs, each with a few $300, 250 GB drives and 50 Mbps connections up 99% of the time.

This section discusses other issues related to the agenda and design of large-scale peer-to-peer storage.

Another strategy to reduce redundancy maintenance bandwidth is to attempt to not admit highly volatile nodes or very similarly shift responsibility to non-volatile hosts. Fundamentally, this strategy weakens how dynamic and peer-symmetric the network one is envisioning. Indeed, a strong enough bias converts the problem into a garden variety distributed systems problem - building a larger storage from a small number of highly available collaborators.

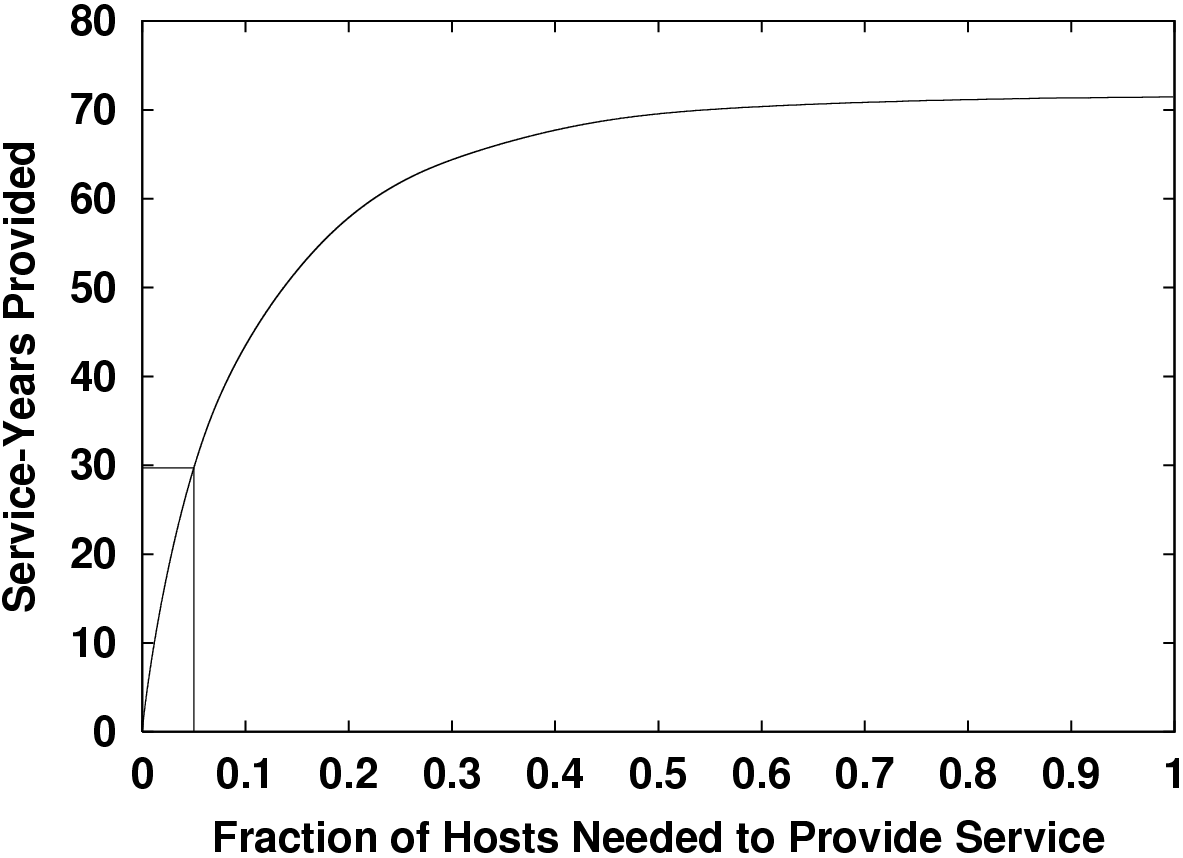

As Figure 4 shows, in Gnutella, the 5% most available hosts provide 29 of the total 72 service years or 40%. The availability of these 6,000 nodes is about 40% on average. If one is generous, one may also view this 5%-subset of more available hosts as a fairer model of the behavior of a hypothetical population of peer-to-peer participants. We repeated our analysis of earlier sections using just this subset of hosts with a one day membership timeout. The resulting bandwidth requirement is 30 Kbps per node per unique-TB using coding. Using delayed response, coding, and admission control together enables a 1000-fold savings in maintenance bandwidth over the bleak results at the left edge of Figure 2.

The total scale of this storage remains bounded by bandwidth, though. If the 6,000 best 5% of Gnutella peers each donated 3 GB each then a total of 3 TB could be served with six nines of availability. These hosts would each use 100 Kbps of maintenance bandwidth whenever they were participating. Assuming the query load was also about 100 Kbps per host, cable modems would still be adequate to serve this data. The same service also could be supported by 10 universities, each using [1/3] of the typical OC3 connections and a $1,500 PC.

Stricter admission control rapidly leads to a subset 967 Gnutella hosts with 99.5% availability. This surpasses even observed enterprise wide behavior [Bolosky et al., 2000]. The cost of this improvement is a reduction in service time by 10-fold. The real service reduction will depend on the correlation between availability and servable bandwidth. Ideally, this correlation would be strong and positive.

If the per-node bandwidth of the best hosts is roughly 10-fold the per node bandwidth of the excluded hosts then the total service is only cut in half by using just good nodes. Stated in reverse, leveraging tens of thousands of flaky home users only doubles total data service. This fact is further backed up by a simple back-of-the-envelope calculation. Two million cable modem users at 40% availability can serve about as much bandwidth as 2,000 typical high availability universities allowing half their bandwidth for file sharing.

The discussion so far suggests that even highly optimized systems can achieve only a few GB per host with Gnutella-like hosts and cable-modem like connections. However, hardware trends are unpromising.

| Home access | Academic access | ||||

| Year | Disk | Speed | Days | Speed | Time |

| (Kbps) | to send | (Mbps) | to send | ||

| 1990 | 60 MB | 9.6 | 0.6 | 10 | 48 sec |

| 1995 | 1 GB | 33.6 | 3 | 43 | 3 min |

| 2000 | 80 GB | 128 | 60 | 155 | 1 hour |

| 2005 | 0.5 TB | 384 | 120 | 622 | 2 hour |

A simple thought experiment helps us realize the implications of this trend. Imagine how long it would take to upload your hard disk to a friend's machine. Table 1 recalls how this has evolved for "typical" users in recent times. The fourth and sixth columns show an ominous trend for disk space distributors. Disk upload time is getting larger quickly. If peers are to contribute meaningful fractions of their disks their participation must become more and more stable. This supports the main point of this paper: synchronizing randomly distributed, large-scale storage is expensive now, dynamic membership makes it worse, and this situation is worsening.

Unlike pioneer systems like Napster and Gnutella, current research trends are toward systems where users serve data that they may have no particular interest in. A good fraction of their outbound traffic might be saturated by access to this data. Storage guarantees exacerbate the problem by inducing a great deal of synchronization traffic above and beyond access traffic. These higher costs may make participation even more capricious than our example of the Gnutella network. Given that stable membership is necessary to reach even modest data scales, participation must be strongly incentivized.

The added value of service guarantees might seem to be one incentive. However, this is not stable since a noticeable downward fluctuation in popularity will make the provided service decline. Another option is having user interfaces which discourage or disallow disconnection, but this is very much against the spirit of a volunteer or donation based system. One reasonable idea is to allow client bandwidth usage to be only proportional to contributed bandwidth. Enforcing this raises many design issues, but since it is an extension to the threat model it seems inappropriate to relegate it to an afterthought.

The conflict between high availability, large data scales, home user-like bandwidth and fast participation dynamics raises many questions about current DHT research trajectories. In dynamic deployment scenarios, why leverage many nodes to serve data a few reliable ones might? In static deployment scenarios, small lookup-state optimizations may do more harm than good in terms of system complexity and other properties, especially if designers insist on implementing other optimizations in membership state restricted ways. If storage guarantees are inappropriate for large-scale peer-to-peer why worry about lookup guarantees? When anonymity or related security properties are the high priority guarantees, it seems bad to plan on incorporating defenses against threats to these properties as an afterthought.

We would like to thank Stefan Saroiu, Krishna Gummadi, and Steven Gribble for supplying the data collected in their study. This research is supported by DARPA under contract F30602-98-1-0237 monitored by the Air Force Research Laboratory, NSF Grant IIS-9802066, and a Praxis XXI fellowship.

|

This paper was originally published in the

Proceedings of HotOS IX: The 9th Workshop on Hot Topics in Operating Systems,

May 18–21, 2003,

Lihue, Hawaii, USA

Last changed: 26 Aug. 2003 aw |

|